58. Sensation Language

Pain is a sensation, and describing pain is a language-game that is, at once, public/subjective, public/intersubjective, and private. Language is a significant tool of the metis and thanthiram (cunning) I habituated to navigate my chronically painervated horizons. Philosophers like Ricoeur and Derrida approach language and truth through disclosure, or language's ability to bring beings from concealment into unconcealment, and displacement, a linguistic phenomenon that shifts words between contexts, languages, and/or generations. The experience and objective of language is perhaps most evident in poetry, as poets seek to bring language itself to language, where a central problematic is the gift of the appropriate word. Unlike everyday ordinary language, which isn't thought to privilege the gift of the proper word, the innovative speech of poetry admits truth from concealment to unconcealment. Van der Heiden (2010) suggests that this disclosure, the unconcealment of being, is the essence of language (pp. 3, 49-51).

Writing appears to represent speech and truth but is concealment from a Platonic standpoint, a limited image of living speech (van der Heiden, 2010, p. 60). Ricoeur underscores that language is a medium for understanding and that distanciation — which is a particular interpretation of displacement — in communication is productive. Distanciation in writing is writing's separation of meaning from the event of its articulation, from its addressee, from direct understanding with respect to its genre, form, and structure, and from the self. This detachability of writing from speech and speaker is productive in that it does not fix the written text as "dead" or as a specious representation of truth; instead, this detachability allows the written text to move freely between different speech communities. Most significantly, writing, particularly fiction, suspends the everyday world through distanciation, presenting a mimesis of the world that both is and isn't our world, making possible the configuration of new worlds (pp. 75-86).

Writers are positioned to stage an empathetic reader response, and to address, or even reverse, the fibromyalgic's inclination towards isolation and silence (Morris, 1998). In the written text, the decipherment of meaning, moving from sign to signified, presupposes a set of nonobvious meanings that stretch beyond the obvious context. In Derrida's account, the reader must attend to interruptions and undecidables in the written text and brace for wholly different discursive paths. Dissemination and displacement illustrate that there is no absolute direction orienting every reading. The boundaries of the semantic whole are ambiguous and indeterminate, refusing to tell us where to begin and end. Speech and writing are mediated by language, and only through language can we create and access signification. As there is nothing outside the text (or language), meaning can never be completely present, and representational absence becomes a form of presence in the resulting play between presence and absence (van der Heiden, 2010, pp. 101-108, 237-254).

From a phenomenological standpoint, writing creates the possibility for hermeneutic consciousness due to its transferability and repeatability, but — like typography and genre conventions — language is abstracting, separating, constraining, hierarchizing, and specious. A single expression may inadvertently suggest that a moment (a part inseparable from a whole) exists as a whole. It may falsely convey that identity is contained in a discrete appearance instead of within a manifold, all presented and possible appearances that can be variously expressed while describing the same identity, whose meaning is within and behind all of those expressions (Sokolowski, 2000, pp. 24-32). As Sokolowski explains, "A cube as an identity is shown to be distinct from its sides, aspects, and profiles, and yet it is presented through them all" (p. 27).

Despite and/or because of its specious nature, language is indispensable to the opening of the world. The language-game of pain — more specifically, bending the grammatical rules of public, ordinary language to convey the vast identity of pain — can reinvent the perception and treatment of individual and collective suffering.

Subjective sensation language, such as writerly poetics, derives from personal affective and sensory experience and is tempered by collective experience. Wittgenstein (1953/2009) suggests that pain is a grammatical language-game governed by the rules of the collective society: for instance, pain cannot be attributed to inanimate objects or colors. In the doctor's office when I use descriptions like my shadow hurts, yellow hurts, I am a once-gaseous planet learning the agony of solidity, there is a long tongue worming from my lips to my colon and every inch of it hurts, pain is whitewater rafting through my left eye, I am not making sense. These descriptions are reflexively poetic, born of sensory and synesthetic associations and experiences and a lifetime dedicated to honing my writerly craft, tempered by an understanding of how to play the language-game — that is, how to comprehensibly present private language to the public sphere.

My pain language can only make sense poetically; literally, it breaks the grammatical rules of the ordinary language-game. Because people habituate a disposition towards bafflement rather than adaptation and inquisitiveness when these rules are flouted, it's easy for my physicians to distill my self-assessments to Patient complains of generalized abdominal pain and reports higher fatigue than usual in my medical records, and for my professors and peers to assume I am describing one identity in a manifold of ways — pain and fatigue — without considering what is intended in the presence (or absence) of specific imagery.

For Wittgenstein (1953/2009), pain is a behavior, not a physical object, but it isn't possible to speak of pain as solely behavioral. He poses two key questions regarding sensation language: "How do words refer to sensations?" (§ 244) and "In what sense are my sensations private?" (§ 246). How does one produce, let alone "master," linguistic expressions of pain, which is widely considered incommunicable and language-defying?

Wittgenstein (1953/2009) questions our conventional understanding of a public language, theorizing that language is always private, as people attach meaning to words based on their personal, affective, sensory experiences, and is inaccessible to others because of individual variation. For instance, when I first encountered a conch "shell" — a souvenir given to me by a white friend — I associated it with "artillery," while my friend understood "shell" in its conventional sense, as the vacated home of a sea snail found washed up on the beach. "Painervation," when I coined it, conjures private associations with the paradoxical exacerbation and relief of pain and fatigue during massage and the acceptance of these affective states it compels. At the same time, Wittgenstein argues that meaning is only generated through social interaction: that is, I couldn't ascribe "artillery" to "shell" without having heard my parents' stories, and "painervation" was intersubjectively created with Sara during a bodywork session.

Wittgenstein's (1953/2009) position seems to be that sensations are private, but sensation words do not take the interior sensations as their meaning (§ 256). Language takes its "basis of articulation in the body, the way bodies and affects are coded within the melodies of speech" (Gibbs, 2005, para. 22), and common words representing sensation don't derive their meaning from sensations themselves but from social and cultural understandings of sensation. The meaning of a word is its agreed-upon use, as Wittgenstein (1953/2009) suggests, and its usage is an agreed-upon practice, or at least a substantial quantity of public practice by the community. In other words, the name "pain" indicates that pain is present, but the pain sensation itself has no bearing on the meaning or use of that particular sensation's name. However, my "pain" is unlikely to match "pain" in dominant discourse, as a nondisabled subject understands it, or even as chronically ill people of different backgrounds understand it.

Wittgenstein muses:

What about the language which describes my inner experiences and which only I myself can understand? How do I use words to stand for my sensations? — As we ordinarily do? Then are my words for sensations tied up with my natural expressions of sensation? In that case my language is not a 'private' one. Someone else might understand it as well as I. — But suppose I didn't have any natural expression for the sensation, but only had the sensation? And now I simply associate names with sensations and use these names in descriptions" (Wittgenstein, 1953/2009, § 256).

Private definitions are in some ways impractical: the name "pain" doesn't come to me until I feel the pain sensation, at which point, I don't need to name it for myself unless the name has a purpose, namely to express the sensation to others. The pained subject gives pain its expression, and from the expression, the listener grasps a meaning that may or may not correspond to the speaker's intention. No language is truly private, and yet all language is private to some degree (Wittgenstein, 1953/2009).

Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons comes to mind, as an exercise in reintroducing readers to language through her private language, blurring the meaning of a word with other words. For instance:

MALACHITE.

The sudden spoon is the same in no size. The sudden spoon is the wound in the decision. (p. 22)

Ordinary language is comprised of a multiplicity of language-games, but each has its own grammar. Public language is a repertoire of these social practices (Wittgenstein, 1953/2009). Stein's Tender Buttons rejects the conception of ordinary language, presenting a seemingly incomprehensible private language that — by virtue of publication — becomes a public language that remains mostly private. This mostly-private language reconceives the language-game as one that isn't a social practice, is subjective, follows a rulebook that is exclusively Stein's, though we are, as readers, invited to play. The two-sentence poem "Malachite" is one example of how Stein uses repetition and metaphorical association to challenge the notion that a word's meaning must conform to public agreed-upon use. These relationships come from private language: suddenness and spoon, same and (in) no size, sudden spoon and wound, wounds and decisions, wounds and sameness and (in) no size. The identity of malachite is contained in this representation of a common green and black mineral used in pigments and talismans for protection and fertility, but it is not an expression that "makes sense."

The shaping of empirical objects through artistic expression belongs to public/subjective language and typically abides by its grammar. But Stein's "word-portraits" extend the possibility of meaning by creating a mostly-private language, destabilizing and defamiliarizing ordinary language. Understanding comes when you stop understanding — when you can detach your understanding from the ordinary language you've habituated and perceive that the word-meaning relationship was always unstable, and that, in many ways, we were never making sense.

Works like Stein's Tender Buttons or Joyce's Finnegan's Wake are unintelligible through the lens of the public language-game since their internal logic and coherence belong to the writers' private language, but these mostly-private language-games are studied and celebrated. By contrast, mostly-private pain language in interpersonal settings in the clinic or academy is dismissed as nonsensical, when it is meant to make a different kind of sense — to revitalize the language around sensations, unconceal being, open the world.

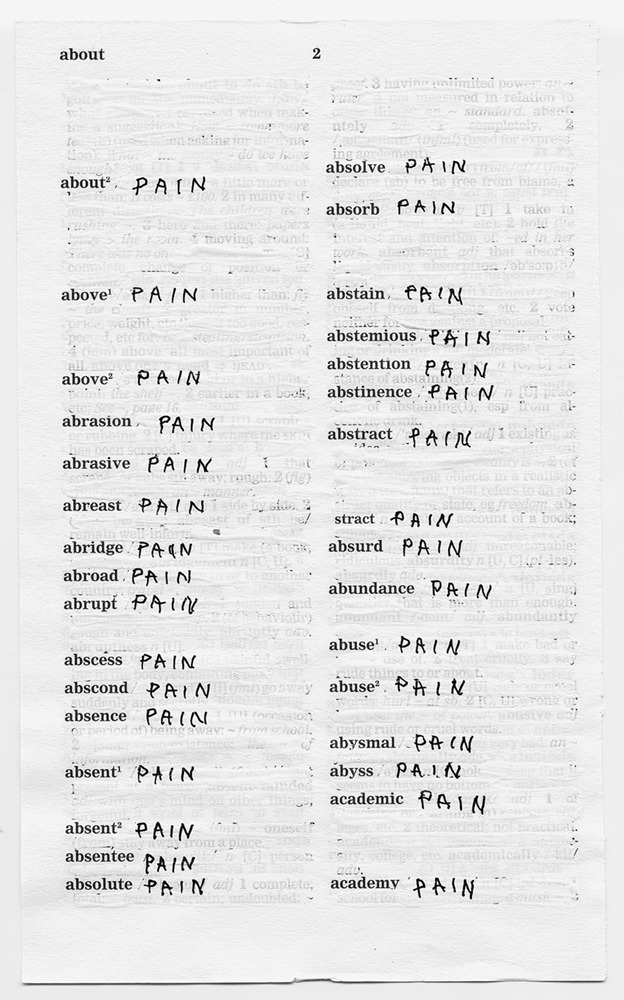

Mladen Stilinović, whose PAIN collection comprises a series of conceptual artworks representing pain, cites Wittgenstein as an influence on a redacted ready-made, Dictionary - Pain. This installation, exhibited from 2000 to 2003, consisted of wall-mounted dictionary pages with redacted definitions, over which is scrawled in handwriting: "PAIN." The exhibit suggests that we encode pain into language on learning language as a concept and a language-game; that pain doesn't exist in language, but all language can be pain. In all my attempts to analyze and explain individual and collective pain, the unshakable truth is that pain is there. In all the body parts. In all the words.

Dictionary - Pain is a language-game, one with more graspable rules. Blackout poetry has aesthetic and activist intentions, defacing a text to expose the meanings that the creator perceives in it. Overwriting texts that exert control over our lives — like dictionaries, with biomedicalized definitions of pain — is a political statement, a simultaneous reclamation of control and an undermining of semantic fixity. Importantly, on these defaced pages, the original definitions are still faintly visible beneath the white-out and handwritten letters. Creative modes of expression are at liberty to conjure up juxtapositions, permutations, metaphors, and poetry that foreground language and validate or invalidate certain experiences as pain (Morris, 1998). We can't completely overwrite a public language with a private one, but we can improve our understanding of meaning as flexible and contingent.

In the indie horror film Pontypool (2008), a disease is transmitted through the English language (as the film is set in Ontario, this is undoubtedly a political statement about the colonization of French Canadian consciousness), and the cure is redefining words as we understand them, abandoning the notion of a public, ordinary language. The answer to the question, "How do you not understand a word?" is to move associations around, make your understanding of a word as exclusive as possible, as private a language as possible. As protagonist Grant Mazzy explains: "You have to stop understanding what you are saying."

Private sensory experience, particularly pain, is more authentically disclosed through mostly-private language than through expected behavioral expressions like I feel pain. To be in pain is to have certain knowledge that you're in pain, while witnessing pain is to have to certain knowledge someone other than you is in pain, and both positions are mediated by language (Scarry, 1985; Kleinman et al., 1998; van der Heiden, 2010). My pain language has mostly-private definitions that make sense the way words make sense at the end of Pontypool. In writing, I demonstrate how their grammatical rules depart from the grammar of the agreed-upon language-game. Like the sensation of pain, such words and grammar can't exist privately and are unimaginable and unverifiable, with no "criterion of correctness" (Wittgenstein, 1953/2009, § 257-261, 272).

We aren't limited to expressions that refer to the factual existence or causes of bodily damage, which aren't the best or only way to solicit empathy or elicit an embodied simulation of pain in listeners. New therapeutic possibilities could emerge from an intersubjective space generated by mostly-private language-games, where pain might be disclosed through collaborative interpretations of ambiguous expressions (Quintner et al., 2008, p. 832).

I describe my pain in ways that don't make sense, but then again, we were never making sense.

The fact is that language isn't private, and language doesn't perform a singular function, namely conveying thoughts (Wittgenstein, 1953/2009, § 304). However, the illusio of academia privileges this function in its scholarly genres, seeking to represent the phenomenological world with a grammar developed to be disembodied, depersonalized, and unprovocative. Meanwhile, I'm playing a different language-game. Like a sommelier with a refined palate who wouldn't understand "Name a good wine," I need languaging more specific than "pain" to understand its meaning. "Pain" means nothing to me anymore without evocative description, the poet's attempt to bring language itself to language. The absences, interruptions, and undecidables in the written text that produce ambiguous, collective meaning can convey the meaning of pain as I understand it. But to adhere to the illusio of the field, where poetics are ousted from traditional social science scholarship, I'm supposed to write about chronic pain in the grammar of public/objective language.

A mostly-private poetics could let us wrest back some discursive control over pain expression and representation, but my desire for a sensation language that reintroduces audiences to language and revitalizes how pain is perceived is pathologized. Disability resides in the notion that pain is unintelligible (and pained bodies are arhetorical) the same way it does "not in paralysis but in stairs without an accompanying ramp, not in blindness but in the lack of braille and audio books, not in dyslexia but in teaching methods unwilling to flex" (Clare, 2017, pp. 12-13).

Perhaps the dream of a common language is this: the realization that the common is an amalgam of the mostly-private, that individualizing metaphor can be accessible, negotiated in a state of togetherness, between patients and doctors, writers and readers, student and professors and peers (Quintner et al., 2008). When we say that bodies matter, we must include the expressions of and about suffering sick-woman bodies like mine that lack the material freedom to relate and conjoin with other bodies (Price, 2015; Hedva, 2016). Representing pain in descriptions from a private language reintroduces readers to pain language and sets the stage for a much-needed collaborative interpretive and creative endeavor.

(–80. Alternative Pain Scales)