83. Modified States

This story takes its inspiration, as many of these stories do, from September 2014, when I found myself in the ER with a ruptured appendix I'd lived with for so long that my pelvis looked like a bomb had gone off. The head nurse gasped when she saw the scarifications on my thighs. "Did you do that?" she asked. "I had it done," I said. She asked about my motivations, the artist's credentials, how much it hurt; she wanted to code me E-980, for intended self-harm. My abdominal pain suddenly became suspect. She insisted on checking me over. "What's your tattoo," she asked when I turned around, tapping the panopticon at the nape of my neck, and I automatically launched into my standard lecture about panopticism, disciplinary power, and opportunities for rhetorical resistance located in the body. When I turned back around, there were multiple nurses behind me, nodding in understanding. The nurse erased the E-980, and we co-wrote the rest of my intake. Regarding my pain and my body symbols, nothing more was said.

Later, Dr. Sattva commented on how "cool" my scarifications were and enthusiastically asked about them, qualitatively altering the dialogic space.

In keeping with misability, whose use of signifiers, gestures, or actions is so habituated as to be artlessly unintentional, it seems to me that I cunningly, accidentally, avoided an institutional miscoding by using body symbols to challenge a reading of the physical body as a static text, which is the province of biomedicine alone, thus un-"sticking" a fetishized affect and dismantling a normative model of embodiment in the process. Detienne and Vernant (1978/1991) and Hawhee (2004) describe Odysseus, renowned for his cunning, as revealing his metis when he is least visible: in disguise. As Hawhee (2004) finds in the interactions between Odysseus and his patron goddess Athena, metis must be deployed to be realized. It's noteworthy that Odysseus' cunning is god-given — state-sanctioned, if you will — just as Zeus' devouring of the goddess Metis allows him to legitimately absolutize his reign. By contrast, in Norse myth, authority similarly belongs to those who can control cunning intelligence, but cunning intelligence is never assimilated into sovereignty; rather, it remains at least partially invested in Loki, the figure who challenges, resists, and overcomes the Asgardian order under Odin (Wanner, 2009, p. 213).

Loki's lips were punitively sewn shut, but lip sewing as a body modification procedure has meditative and political valences, as a religious act or means of spectacular protest.

The ancient Greeks used tattoos (stigma) as a penal mark in their own society but understood tattoos contextually, able to appreciate tattoos as poikilos — the fascinating effect of a many-colored, many-spotted, multisensory design, as in embroidered textiles or patterned jewelry, as well as the mental agility attributed to metic intelligence (Rees, 2019, p. 284; Fine, 2021, p. 154). As ambivalent as metis, poikilia is "a privileged mode of sense-perception. . . . [that] refers not merely to a property of an object but essentially to a fascinated experience of a perceiver" (Fine, 2021, p. 153). Snakes, whose complexly patterned, iridescent scales fascinate their prey and camouflage them from predators, are poikilos: beautifully, dangerously wily (p. 155). Odysseus, Prometheus, and Medea are described as poikilometis, dapple-skilled, various-minded, able to manipulate senses and minds by captivating their interest.

"A poikilos mind cunningly uses a poikilos artefact" (Fine, 2021, p. 156), and if body modifications have been historically described as poikilos (Rees, 2019), then perhaps the modified fibromyalgic wears a cunning tapestry atop her cunning fascia — literally. Viththiyaasam made visible. As my experience in the ER demonstrates, subcutaneous markings imbue me with weird potentials through the conflicted attraction they inspire in viewers as well as in the opportunities they stage for me.

For the FMS patient, cunning becomes her way of being and of encountering the world, such that the somatic masquerade becomes a polysemic identity in all her contexts, a multifaceted and "tricky" presentation that receives a range of responses and interpretations, out of which she can select the most favorable or advantageous. Every encounter becomes a wager, from a crowded subway car to a classroom to the outpatient wing in the ER, in which the stakes of stigma management are high and performance is spontaneous and contingent (Goffman, 1990). I can't create illusions like Monkey or transform myself like Loki, but I can irrevocably alter the morphology of my body. I've been a body modification enthusiast since 2007 and a lurker on Body Modification Extreme (BME) Ezine forums since the late 1990s, around the time I found myself needing wrist and knee braces. The "modded" fibromyalgic subject can use the contours of her body in unwitting, intuitive ways to elicit certain responses to her non-apparent condition, by chance, that can then be fortuitously and spontaneously used to circumvent or interrogate state-sanctioned institutions and technologies. She can also use them to activate her myofascial awareness through inner touch.

At this time of writing, I have nine piercings, 13 tattoos, two scarifications, and a small neodymium magnet implanted into my left ring finger. I wear the artwork of 12 body modification artists. Each of these modifications has advantageously and detrimentally changed my relationship to chronic pain and how I interface with the world. Misability inheres in these "poikilos artefacts" and how my misabled poikilos mind harnesses them: how they visibilize viththiyaasam on my non-apparently different body, how they non-verbally offer perspectives, how they invite verbal exchange. They permit me to shimmer in and out of difference, to mingle flexibly and well (Fine, 2021, pp. 161-163). As they are so much a part of me that I forget them, I end up using them adventitiously, in keeping with misability and tricksters who might be broadly construed as its patrons, like Sisyphus, Coyote, or Loki — the clever ones who act on the fly and aren't infallible.

Traditions of Body Modification

My great-grandmother regularly walked on hot coals at religious festivals; other relatives engaged in kaavadi, or burdens, enacted through body suspension, piercing their cheeks with skewers or their backs with metal hooks attached to a portable altar to Murugan that is carried or pulled in a religious trance. My first two lobe piercings and nose ring, the only piercings Amma finds acceptable, are significant in my culture. In Hindu practice, a child's ears are ritually pierced in Karnavedham, an ear piercing ceremony that takes place before the age of five and is thought to make the ears receptive to sacred sounds that cleanse and nurture the mind. As with many Indigenous body modification practices, nose piercing has a therapeutic component, and piercing the left nostril, like mine, is associated with channeling feminine energy and relieving female pains. Ear piercings have also been associated with acupuncture: lobe piercings address depression and anxiety; industrial piercings reduce allergies; rook piercings mitigate stress; daith piercings, thought to stimulate the vagus nerve, help with migraines; and conch piercings, which I have yet to get, alleviate chronic pain. Modifications may also include other inscriptions and transformations of the body surface, as with prosthetic limbs, sensory augmentation, or other external changes (Pitts-Taylor, 2003).

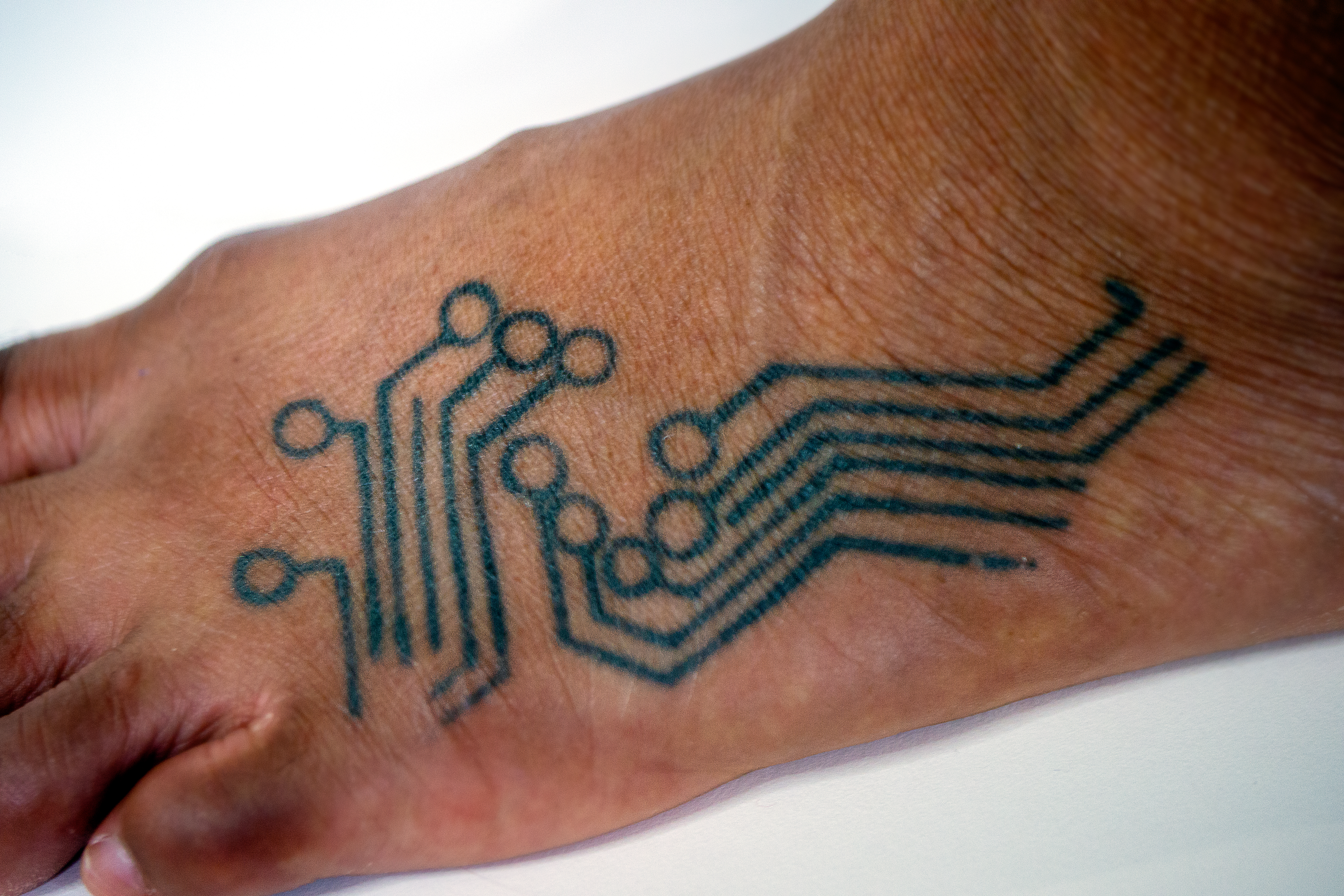

My great-grandmother also did pachai kuthu, the ancient practice of tattooing in Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka that was decimated by colonization. Still practiced by some tribes, pachai kuthu involves street stick-and-poke tattooing using an ink mixed from milk, soot, and herbal powder, resulting in green linework. Pachai kuthu tattoo compositions tend towards names — to establish kinship networks or for identification purposes in a crisis — kolam designs, or labyrinthine patterns designed to confuse or ensnare evil spirits. They were often placed for pain relief, similar to Ötzi the Iceman, whose 5,000-year-old body displays the earliest signs of tattooing in the archaeological record, or to ancient Egyptian tattoos, which are suggestive of pain relief or aesthetic appeal. Many modifications categorized as extreme have their origins in Indigenous practices as well, such as cranial binding (performed across time and geography), tongue splitting (depicted in Hindu artwork and considered the height of the Khecarī mudrā in Hatha yoga), genital beading (common in the precolonial Philippines), and minor amputation (like yubitsume, the removal of finger joints as penance to a superior).

As an Indigenous practice in South Asian, Native American, African, and Polynesian cultures, to name a few, body modification was woven into the social fabric of existence, used to denote caste, genealogy, age, and marriageability; to enhance sex appeal; or participate in ancestral or mythological traditions. It can be a symbol of collective identity, communal solidarity, or status as well as a medium of self-actualization and communication. According to Turner (1999), in traditional societies, the body is a space to think about and constitute the body politic. In these societies, tattoos were fixed in social meaning, linking human embodiment to social processes, particularly reproduction. He observes that postmodern society has resituated body mods within a cultural framework where "cool readings" — ironic and simulated interpretations of consumerist cultural capital on a bodily surface — are the only interpretations possible. Nevertheless, human embodiment and social processes are just as linked in modern societies as they were in ancient ones. In traditional societies, subcutaneous markings denote an individual's progression through her life cycle: birth, puberty, marriage (pp. 39-40). In modern societies, tattooing and branding have been used by the state for classification and stigmatization. Coopting and blending Indigenous and foreign motifs and styles of tattooing, the aesthetic tattoo of the white middle-class are "surface indicators of identity and attachment . . . an exhaustion of idiom" (p. 49).

Raised middle-class American, I belong to groups where body mods mark cultural membership, as a Tamil woman (nose piercing) and a queer woman (tattoos). Body mods like these signal thick social commitments while also suggesting ironic coolness, simulating traditional communalism in a society likened to an airport departure lounge (Turner, 1999, p. 46). Subcutaneous markings don't always signal social commitments within the disability community, but they do connote the process of working through corporeal vulnerability to explore the bodymind's contingencies and unknowns, and within the grinder community, there are a number of disabled individuals, including those with autoimmune disorders and debilitating allergies (Doerksen, 2018, § 2). Grinders practice functional body modification to improve the human condition. The grinder project of sensory extension, for example, attempts to take what is different and amplify its difference to discover and explore unknowns about the body. Grinder culture, or biohacking, perceives body modification as a way of contesting what is "normal" to challenge the social phobia of the unknown, abnormal, abject body (§ 2).

Of particular significance for the chronically painervated, Turner (1969) observes that body symbols "establish a channel of communication within the individual between the social and biological aspects of his [or her] personality" (as cited in J. Myers, 2011, p. 298) and, where visible, with society through the revelation of information indicating alignment with a system of beliefs and values. Although they no longer denote social processes or reproductive cycles, body symbols retain an association with oppositional culture, as body mods during periods of nation formation were often utilized by the marginalized to express class or occupational solidarity and were accordingly interpreted by the State as symbols of the criminal underclass or other "deviant" groups — as happened to me in the ER (Turner, 1999, p. 45). This is especially true of non-whitestream "extreme" modifications, like scarification, or art etched with a scalpel; branding, or markings burned into the skin with a hot iron; subdermal implantation of medical-grade objects, like a parylene-coated neodymium magnet, RFID chip, or silicone beads to alter the body's contours or interfacing capabilities; sexual modifications, like the apadravya piercing (possibly mentioned in the Kama Sutra) or transdermal penile implants; and intentional deformation.

Pain is an inevitable part of the process, and if you choose a modification, you tend to accept the experience of pain (J. Myers, 2011, p. 292). It's also a method for practicing acceptance of pain you already possess, and for women, perhaps, building shakti.

Tattoos are far more mainstream today than they were at their outset in whitestream society, and many body modifications are also more common and more safely performed, but they retain the stigmas of illegality or illicitness, (sexual) deviance, and punk subculture. I began modifying my body as a means of managing diverse, unpredictable forms of disability stigmatization by externalizing a particular character trait in the form of a hypervisible, stigmatizing feature, thus focusing others' attention on that trait and not the rest of my "spoiled identity" (Goffman, 1990). I got my first tattoo in 2007, the same year I was officially diagnosed with fibromyalgia and one year after the onset of my symptoms. It was a sizeable black linework tattoo on the lower back, and my artist marveled at my calmness during the session given that I was a "tattoo virgin." It was a tickle that filed my usual pain into closets. It was a poikilomētis way of reclaiming an unruly body, of choosing my own pain for a while instead of enduring the pain I have no choice in. And it was a way of actively trying to modify my senses myself, instead of passively allowing pain to do it for me, to participate in how my fascia makes sense of the world.

In mainstream society, it still seems better to be a queer punk rebel than a disabled, un(re)productive woman.

Altered States

Fibromyalgia is complicated by the intersubjective dimensions of pain, and the ways in which chronic pain must be understood as an expressive activity in which others can be involved as witnesses and participants (Merleau-Ponty, 1945/2012; Svenaeus, 2015). It is necessarily environmental, like the phenomenological perspective that asserts that places define the living conditions of all things and suggests that "human beings are biocultural creatures constructing themselves in interaction with surroundings they cannot not inhabit" (Alaimo, 2012, p. 8). Bodies may be capable of "knowing" things, may be able to trap us in our habitual movement, permeated by sociopolitical landscapes that manifest as the physiological effects of oppression, trauma, capitalism (Morris, 2000).

Western biopolitics problematically frames pain, especially female pain, as an undesired affect that should be quickly suppressed to enhance the (re)productivity that is beneficial to the state. But with its absences and fluctuations, acute pain is the body's warning system, and chronic pain too, perhaps cryptically, warns against something — if not a hot stove or imminent collision, then precarity, disciplinarity, the denigration of self-care. Grinders have linked the practice of body modification to resistance to the state and to the logics of precarity and control. As Doerksen (2018) observes, "because grinders are neither very vulnerable nor very privileged, their projects are positioned to expose power structures that may benefit the disproportionately vulnerable" (§ 2).

Pain is a social and economic problem, and technological advancement has not brought us to a state of unprecedented health. FMS and ME are disabling conditions that regularly remove a vast number of Americans from the workforce, and so pain must be absorbed, categorized and legitimized for legal and economic purposes; it must be alleviated through Western allopathic treatment; the subject must remain dependent on a healthcare system that promises cure and increased productivity. The infliction and alleviation of pain are constructed as instruments of biopolitical control that can't belong to the people, so the state and biomedical complex have a hypocritical attitude towards elective, non-medical aesthetic and sensory modifications. Only mods in service of (re)productivity are legitimate: liposuction versus auto-amputation, implanted pain pumps versus microdermal implants at acupressure points, or breast implants versus an implanted magnet (Sullivan, 2005; Foucault, 1963/1994).

According to enthusiasts interviewed in ethnographic studies, body modifications enhance awareness of corporeal parts and processes that are rarely perceptible or are only perceptible when performing their prescribed purpose. For example, sex organs are more noticeable when weighted, and the addition, removal, or changing of ear jewelry or scalpelling of the ears changes how we hear (J. Myers, 2011; Pitts-Taylor, 2003; Sullivan, 2005). As suggested by the work of body artists like Stelarc, Orlan, and the late "supermasochist" performance artist Bob Flanagan, whose cystic fibrosis was chronically painful, the sensory-enhancing potential of body modification parallels and visually and haptically externalizes the inwardly focused modes of attention that belong to interoceptive sensitivity (Massumi, 2002). Interoceptive sensitivity "folds tactility into the body, enveloping the skin's contact with the external world in a dimension of medium depth: between epidermis and viscera" (p. 58). Such modifications are poikilia, creating a "privileged mode of sense-perception" for the modified subject (Fine, 2021, p. 153) and the experience of fascination for the audience.

Misability knows that a captive audience is easier to persuade.

While continuous self-attention through the so-called minor senses may promote self-absorption, studies like Grynberg et al.'s (2015) illustrate an interdependence between interoceptive sensing and empathy for pain (p. 55). Doerksen (2018) also finds that pain was part of what was community-building about Grindfests. Grinders bonded by disrupting what was knowable about the body and communally witnessing and enduring painful experiences, using both techniques of body modification and state control — from scarification to waterboarding — to simultaneously confront corporeal vulnerability and experiences that the state keeps hidden (§ 2). While enthusiasts' reasons for undergoing body modification varied, basic commonalities included the desire for these altered states of perception and community formation around the shared experiences of intimate pain, self-care, and visible markings. At the same time, this empathy may be limited to communities that visibly share this specific experience of pain and sensory alteration and may be further divided between mainstream (piercing, tattooing) and nonmainstream (scarification, implants, trepanning, self-amputation) communities (J. Myers, 2011).

According to Pitts-Taylor (2003), subcutaneous markings reflect a desire to concretize in the body the fact that the body is culturally shaped, always marked, always subject to medical monitoring and intervention, and thus never "natural" (pp. 29-30). If disability is thought to challenge lifelong presumptions about the stable, bounded, normative body, then grinder logic dictates that we change what life and the normative body are (Doerksen, 2018, § 2). The modified fibromyalgic subject amasses subcutaneous markings to perceptibly exaggerate what disability has taught her, that bodily norms lack fixity. Despite this, or because of it, mods do more than simply depict an ironically cool concept or aesthetic pattern, as with my tattoos of a panopticon diagram and the glider from Conway's cellular automaton, the Game of Life. Like the signs of non-apparent chronic illness — visually communicative to those who know what seemingly innocuous or trivial signs mean — tattoos signify even when the specific design isn't a widely recognized one, and the markings themselves create alternate pathways for sensing.

These currently medically unsanctioned intensities were once legitimate medical practice, meant to alleviate pain and enhance peripheral thinking. Hippocrates, Galen, and Eastern and Vedic physicians all purported that ear piercings help regulate the body and open the ears to sacred sounds, with gold piercings renewing a deficiency in (electrical) energy and silver countering an excess. A therapeutically placed daith that can be gently manipulated can alleviate migraines. A cut frenulum in Hatha yoga permits the tongue to touch the uvula and nasopharynx and thereby attain a higher consciousness. More than aesthetic enhancement or anatomical extraneousness, such modifications hinge on sensation, not "pain," which is semantically negative and not automatically presented as an asset (J. Myers, 2011).

Bodies respond differently to subcutaneous markings. Due to temperature changes, seasonal allergies, stress, and chronic inflammation, my fully healed, ordinarily flat-lying tattoos become raised, rosy patterns on my skin, sensitive to clothing, air, and touch. One of the horizontal lines in the scarification on my right thigh, slightly hypertrophied, gives me something to sense through pants, a place to put my fingertips and refocus the intensities. My magnetic implant extends my sense of touch, vibrating near electromagnetic currents and sticking to ferrous materials or magnetized surfaces. My ear piercings, which I fiddle with constantly, are also recentering, shifting my interoception from gut to ear cartilage, the sensation of a titanium bar's smooth slide within the piercing holes.

Where most mods are obviously a means of feeling outward, we must recognize that one of the earliest impetuses for body modification was the desire to increase feeling inward (J. Myers, 2011; Pitts-Taylor, 2003). Viewed in this way, medically unsanctioned body modifications are entangled in procedures that enhance the body as a medium from the inside out. This multi-directional sensing is the inner touch that identifies the boundaries of our bodies, that tells us where the flesh begins and ends (Heller-Roazen, 2007). The notion of boundedness is easily troubled by modifications like a magnetic implant, which is frowned on by medical institutions for its risks and for being an aesthetic rather than medical procedure. Whether mainstream, "extreme," or intentionally disabling — like the acquisition of a physical impairment to align the body with one's core identity — body modifications are designed to alter our modes of attending to our physiology, to make us aware of "the small dance" of the body, all the micro-movements of orientation, postural alignments, muscle contraction and relaxation, and balancing (Sullivan, 2005; Dumit & O'Connor, 2016; Doerksen, 2018).

For normative and FMS bodies, modifications heighten our anatomical consciousness. We reconceive our muscles, attentions, and sensations as accretions of habit, and our patterns of movement and stillness as sensing and forming bodies and selves (Malabou, 2012; Dumit & O'Connor, 2016). As such, mods may contribute to the peripheral thinking of fibromyalgic cunning by unexpectedly drawing attention to the body's "edges" and to alternate ways of sensing the body's interior and the world in which it moves, as well as by providing a social dimension to giving, receiving, and, perhaps most importantly, expressing and witnessing pain.

The Stare

Leder (1990) suggests that the body exists in a default state of corporeal absence, until disruption causes the body to appear, which he terms dys-appearance: the appearance of the body due to dysfunction (p. 98). Social dys-appearance results when stares make the subject aware of the body's impairments. Corporeal and social dys-appearance may occur due to material or environmental conditions, like hunger, pollution, sunburn, load shedding, racism, illness, and body modification. Body mod enthusiasts, grinders, and DIY biohackers tend to reject the parameters of the body as defined by institutionalized biomedicine, perceiving the biomedical industry as reactive, designed to "normalize" bodies, when it should proactively work to "address the increasing disparity between bodies and their socio-material environment . . . to save humanity from its own biological limitations" (§ 3). However, this belief does carry eugenicist overtones, and its emphasis on creating sensorily superior bodies does suggest that nondisabled bodies are inferior and disabled bodies doubly so. The presence of disabled grinders in the community doesn't necessarily negate this criticism, because the collective interest in supplementing or enhancing the human sensorium is often positioned as the search for a superior ability, casting certain disabilities — like synesthesia — as "super-crip" in nature and others as limitations.

However, grinder culture's critiques of how the body dys-appears, socially and medically, do provide insight into problems with the medical industry and the biopolitical imperative to normalize and standardize subject bodies. The medical industry has come to be increasingly driven by government regulations, profit maximization, risk and litigation avoidance, and the monopoly over how to gain legitimate medical experience. Where even barbers were once skilled in bone-setting and tooth extraction, medical admissions, medical curricula, and government regulations now restrict who has authoritative medical knowledge, and who can perform certain procedures legally. Modern Western medicine reproduces the hegemonic norms described by scientific discourses of health, dys-appearing unfit bodies in the clinic and attempting, through cure or medication, to restore their absence (Leder, 1990; Doerksen, 2018).

By contrast, biohackers, body modders, and grinders seek to overturn the definition of "fit," a goal that inadvertently challenges the stares that socially dys-appear the disabled or "freakish" body. Staring, Garland-Thomson (2009) informs us, is not the same as looking: "Staring bespeaks involvement, and being stared at demands a response. A staring encounter is a dynamic struggle — starers inquire, starees lock eyes or flee, and starers advance or retreat; one moves forward and the other moves back. A staring interchange can tickle or alienate, persist or evolve. Staring's brief bond can also be intimate, generating a sense of obligation between persons" (pp. 3-4). When my disability reveals itself — in struggling up the stairs, favoring an arm or leg, incommensurately reacting to painful stimuli — my body dys-appears and draws stares that are disbelieving, mocking, or sometimes, predatory. When my body mods are exposed, my difference revealed, I draw stares of a different kind. This dys-appearance is a dysfunction — a deviation from the norm or disruption to a specific bodily organ, like skin — that I chose for myself.

There are social prohibitions against staring, but social expectations about how bodies should appear and behave trigger the stare when those expectations aren't met (Garland-Thomson, 2009). Chronic illness triggers the stare when it appears in a body that looks fit. If I'm stared at for my body modifications, in public or in the clinical encounter, it's because they aren't expected on my disabled Tamil woman body: American society constructs body modifications as white, masculine, working-class, punk. The stare can single out a body as freakish, as admirable or enviable for its difference, or as an inexplicable phenomenon that demands explanation. Over time, tattooed skin, scar lines, cartilage tunnels, and the electromagnetic sense become interiorized and ordinary in the modded body and to the modded self, but they remain extraordinary to others. Grinders often apply their mods, particularly non-apparent implants like magnets, in tricky ways, performing "magic tricks" at parties or bars, slyly demonstrating "telekinesis" to an undergraduate class, casually playing with it during meetings or a commute and attracting confused and awed stares (Doerksen, 2018, § 6). Wonderment shifts the relations between bodies, requiring openness and a suspension of disbelief that is, like Trickster's mode of doing and being, productive, generative, and reinvigorating.

However, the wondering stare is difficult to stage with clinicians, who perceive themselves in a gatekeeping position of authority over the biological body and interventions into it. Body mods present implications for the relationship between different kinds of expertise. There's a kind of academic paternalism in the biological sciences; public participation in scientific knowledge production and medical intervention is unheard of, and legitimate biological interventions are performed in a hospital setting by a surgeon, not a piercer or body modification artist. The battle for expertise is often framed by clinicians as solicitousness: it's just not safe. Physicians touch my scarifications — ignoring the old but obvious self-inflicted scars on my arm — and compare them to self-injury. Dr. Jiang tells me, after my fourth tattoo, "You don't need any more; you don't know what it's doing to you." After a partial axillary lymph node dissection in 2012, the surgeon tells me with a mix of shock and astonishment that the lymph nodes are non-malignant but blue-black from tattoo pigments deposited in them over time. I had lymphadenopathy in that armpit since high school, before I got any mods, but she's inclined to believe the ink caused the swelling because tattoos pose "unknown health risks."

And in 2016, at Dr. Kyrios' request, I go to get a brain MRI to reevaluate the possibility of Chiari malformation, and the white male radiologist stares at me like I'm not real when I tell him I have a magnetic implant in my left ring finger. "My referring doctor knows," I say, "But it's only my head going in the machine, can I just cover it or close my fist?" He scoffs, "Who told you that? It's a powerful magnetic field; you can't shield a magnet from it." As though to prove his point, he grabs my hand and pulls it into the machine. The magnet flips, uncomfortably dislodging tissue around it, and stands out stark against my skin. I'm too startled to accuse him of violating my rights, as I would never receive a hand MRI with a magnetic implant and didn't consent to being touched, and he lets go before I can formulate a reply. I pull my hand back, all my nerves awake and pulsing, and make it worse by saying, "See? It's fine. And unless I'm wrong, I didn't think the hand entered the machine for a brain MRI." He shakes his head no. Nearly in tears, I go to re-dress, but as though he's satisfied with my subjugation to his medical authority, he waves me back over with a weary sigh, saying, "All right, we'll do this. Tell me if you feel anything strange."

Poikilia as pejorative, but still intriguing.

This choreographed challenge to biomedical expertise occurred because I announced the presence of my otherwise non-apparent magnetic implant. The radiologist reasserted his power by gendering the interaction, treating me like a silly girl easily brought to tears, and forcibly inserting my hand into the MRI machine, as though to prove that the magnet would be ripped out (what he would have done next, I'll never know). I like to think he relented because the exchange forced him to see that my implant remained stable and magnetized in the MRI machine, serving as a reminder that while it's safest to default to a simple rule — no metal in the room — magnetism, metallurgy, and bodies are highly complex affairs, taken separately or together.

Had my implants been medically sanctioned — like internal neodymium magnets used to relieve acid reflux — I might have been refused the MRI with more kindness and respect. Implants alleviating a health condition are essential. Implants that subscribe to the social fantasy of feminine desirability are legitimate. But sensory experimentation practiced by the self or a body modification artist — magnets in the fingertip, or in the ears to function as speakers, or in the clitoris for sexual enhancement — is considered frivolous and dangerous. Body modifications endow the subject with a poikilometic sense-perception that makes the very experience of the world and the pained body fascinating. For the modified fibromyalgic subject, the various minds of poikilometis emanate from the aggregation of her body mods, as each one alters her sensory perception in ways specific to the type of modification and where it is placed.

The medicinal aspects of subcutaneous markings are underresearched, and reports of their therapeutic effects are typically anecdotal or statistically insignificant. And yet, medical markings and technology have been incorporated into the body: pacemakers, intrauterine devices, catheters, dermal sensor tattoos use colorimetric ink that changes in response to biomarker shifts, NFC chips can serve as implanted medical bracelets, chipped pills that transmit information about the body that consumed it. In addition to mods that normalize the (re)productive capacities of the body, some of the more acceptable aesthetic body modifications work to rehabilitate deviant or "freakish" bodies: for instance, 3D nipple tattoos (for breast cancer survivors or transgender people), or reconstructive plastic surgery (for facial deformities, burn injuries, and so on).

Certain body modifications intentionally amplify the stigma of disability, sometimes requiring a body that is viththiyaasam. Witch's piercings, or piercings between the toes, require syndactyly. The rare Achilles piercing, a high-risk modification, can only be done if the client has a prominent Achilles' tendon and sufficient space between the tendon and ankle. Such a modification — placed and named for the hero's somatic difference — transforms a state-sanctioned intervention into a biohack that recalibrates the body's very relationship to movement.

Grinders come from heterogeneous ideological, educational, and professional backgrounds and social milieus, and their reasons for sensory modification vary as a result: as Doerksen (2018) comments, a body mod that is ideological for a white man, like an implant that neutralizes tasers, becomes politicized and practical in a Black man's body. This multitude is organized around a shared interest in experimenting with sensory modification, engaging in a democratic open science, and challenging government regulations around medicine and bodily autonomy (§ 3). The issue of bodily autonomy has long been critical for the disabled community, so presumably, disabled biohackers are more acutely aware of the hypocrisy of Western biomedicine. A hospital ethics committee, after all, supported the parents of Ashley X, a girl born in the late 1990s with severe developmental disabilities, who subjected their daughter to a medically unnecessary hysterectomy, bilateral breast bud removal, and appendectomy to prevent puberty and stunt her growth. Disability rights groups have denounced the Ashley X treatment as profoundly eugenicist, tailored to her nondisabled parents' desire to keep her childlike. This intervention is legal. Meanwhile, I get shit for having a magnet in my finger.

Perhaps there are reasons that aesthetic body mods are popular in the disability community — like a fuck you to a medical establishment that barely construes us as human but still seeks to control what we do with our skin, our flesh, our sex life, our senses.

There is a resistive and tricky symbolic power to medical knowledge and the unsanctioned biohack, particularly when it is located in the disabled body and alters the human sensorium. Doerksen (2018) suggests that, for grinders, sensory experimentations are motivated by the underdetermined, over-regulated nature of the medico-scientific body. I have an understanding of the appropriate depth for subdermal incision as well as how to sterilize tools and clean wounds. I know how to anchor my jumpy vein with a finger and stick a needle in before it slides, adjusting the tip in the vein to draw blood myself, a skill I likely share with patients whose regimen includes self-injection and with recreational drug users. My panopticon tattoo is often my first indication of inflammation and an impending flare-up, and if the skin becomes raised on the snail on my ribs, then I know the flare will be severe. The occasional itch of the figure of Sisyphus heaving a Deleuzian rhizome on my right arm, a usual suspect for pain, reminds me to think my right shoulder back and down. My scarifications know temperature like my joints know barometry, reddening in the heat. Fiddling with my piercings alters my awareness of pain and how I attend to it. My magnet, a private, interiorized sense, was an exercise in gauging the neuroplasticity of a chronically pained body: after the implant, I found that previous sensory experiences influenced my perception of new electromagnetic senses. Sensitivity to pressure in that finger, due to the magnet's proximity to skin and nerves, compels me to attend more closely to how I hold not only that finger, but also the rest of my body.

The Hour of Consciousness

Elsewhere I discuss the metis of Sisyphus, but perhaps he is a touchstone for body modification and medical authority as well. Camus (1955) describes Sisyphus' torture:

One sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to roll it and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees a face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with the arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earth-clotted hands. At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments towards that lower world whence he will have to push it up again towards the summit. He goes back down to the plain. It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step towards the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. (p. 121)

The excessively physical punishment for violating sociocultural codes of conduct — a punishment that, ironically, also delivers the immortality Sisyphus sought in life — socially and materially dys-appears his body. In the act of pushing his stone, Camus' Sisyphus experiences an intensified physical awareness that, particularly at the moment of return, bestows on him a heightened clarity. Camus' description is comparable to the ritualized physical stress and pain of undergoing body modification, which converts torment into a kind of proprioceptive and interoceptive agency. The ability to think in one's edges, a cunning skill in and of itself, is an unrecognized reward embedded in his punishment.

Monitored by the gods or state, the cunning body adapts to attain its goal even in adverse consequences — Loki's lips sewn shut, Monkey controlled by Tripitaka's painful spell, Sisyphus bound to his boulder (Wanner, 2009, 2012; Raphals, 2018). Loki might be an archetype of misability given his cleverness, susceptibility to accident and capture, and the subcutaneous markings from the punitive lip sewing he tore out. The message in the myth is that Loki is not so easily silenced, but his sense-perception around speaking must have evolved after that.

In contrast to tricksters like Loki or Monkey, Sisyphus is not a humorous figure and meets with fewer accidents resulting from his tricks. If he is instructive, he teaches us that it is possible to challenge the Power and win and to find purpose even in absurd torture: "Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn" (Camus, 1955, p. 121).

Body modification is similarly defiant: it circumvents Western sociocultural codes, permitting the non-apparent or concealable mediation and expansion of the senses, creating a polumetic, poikilometic body that is differently sensed by others and to whom the world is differently sensible. The process of body modification, as ritualized pain and discomfort, can help exert control over the self in psychologically beneficial ways. Subcutaneous markings cause the body to ache and bleed, requiring self-care, leading to a sense of accomplishment for enduring pain, expanding and experiencing subjectivity to the fullest, and healing the body (Pitts-Taylor, 2003, p. 32). For the fibromyalgic patient, whose body is confined by medical codes and admonitions, body modification bestows a similar lucidity on constantly noisy flesh. As ritualized pain, it is a chosen discomfort that reclaims the unruly body. As an unsanctioned procedure, it responds to the authoritative insistence on medically normalizing the body to overcome the limitations of illness; it challenges state-sanctioned medical legitimacy.

I feel an instinctive kinship with pierced and tattooed women of color, queer women, and disabled people, reading in these markings shared cultural affiliations, ideological stances, desire for bodily autonomy and, in poikilometis fashion, an intermittently visible identity. For those of us who desire and can tolerate receiving subcutaneous markings, aesthetic body mods express our collective desire for a different type of society — an accessible, inclusive one that doesn't demand visual proof of disability. Body mods, in their multivalence, are a way to cunningly circumvent those demands: to signal high-functioning capacity or a non-apparent disability or to cheekily emphasize a visible stigma: for instance, a muted-audio symbol under a deaf ear, a forked tongue to which nondisabled listeners will likely attribute a speech impediment, a rainbow infinity symbol for autism or neuroqueerness, a zebra for Ehlers-Danlos, a pink ribbon for cancer, a purple ribbon for fibromyalgia, a spoon for chronic illness, a biomechanical tattoo on an unimpaired leg to complement the prosthesis on the other.

These are collective symbols of social cohesion, each motivated by particular stories and reasons. They entice onlookers into joining conversations about disability, in which we might inform or discomfit our interlocutors. For instance, a safety pin tattooed on my collarbone reminds me to keep it together and speaks to a punk DIY aesthetic, but it also brings to mind an early sign of my non-normative sensory processing: how when I was a girl, I hated the feeling of press-on nails but habitually pierced the tips of each my fingers with safety pins, sometimes to the point of bleeding, and decorated those pins with charms, beaded strands, and earrings, then dragged my pierced fingers over every surface in my room to see how it felt. Strangers receive one of these stories more uneasily than the other; I can decide on the fly which one to tell.

Visible body modifications allow us to occupy public space as disabled people, serve as disabled representation, and express crip kinship and solidarity. I have seen that purple ribbon and rainbow infinity symbol in public, and they resonate with me, the same way my rib tattoo of a flame lily, the national flower of Tamil Eelam, resonated with Tamil friends.

Chronic pain can be strategically managed through an intensified attention to and privileging of interoceptive perception, recasting the ability to "think in one's edges" as a reward. Body modifications lend themselves to the FMS patient's stigma management, somatic masquerade, inner touch, and heightened lucidity. They permit the resistive reclamation of an anomalous body whose health is tightly controlled by the biomedical complex that determines which of its sensory experiences are legitimate and which are malingering.

At the top of the hill, where Camus (1955) imagines him happy, perhaps the purpose Sisyphus finds in his absurd task is this ability to think in his edges (Dumit & O'Connor, 2016). There is something misabled about this. In that pause, the breathing-space of the descent, the decrescendo before pain begins again, pushing a boulder or surrendering on a massage table, the suffering/modded misabled body asks of us: What is worth sensing? How does the suffering body sense and make sense? Body modifications help answer these questions by cunningly exposing the porous nature of the body and contributing to lucid insights for the bearer about her body, how it perceives, and how it is dynamically perceived as it moves through the world.

(– 92. Discourses of Power)