81. An Archive of Proof

What instilled in me this magpie instinct to hoard evidence of my lived experiences, the Tamil genocide or a contentious past with doubting clinicians? I self-document with an artist's instinct for timing, subject, and framing, without knowing if the resulting photograph will come of use. Anything might be proof. Anything can be archived. I trust my misabled gut to tell me what that proof might be.

The sick woman of color accumulates a surfeit of self-knowledge that can't be dismissed as malingering or faulty memory: dated handwritten notes, timestamped selfies, symptom logs, journal entries. Padfield (2020) declares:

The photograph, even in a digital age, is imbued with ability to document truth, and for this reason it is an apposite medium, with which to document and manifest the subjective experience of others. A photograph provides a shared space as a reference point, and its polysemy reminds us of the necessity of negotiating language to understand exactly what another might mean — your pain is not the same as my pain. (p. 97)

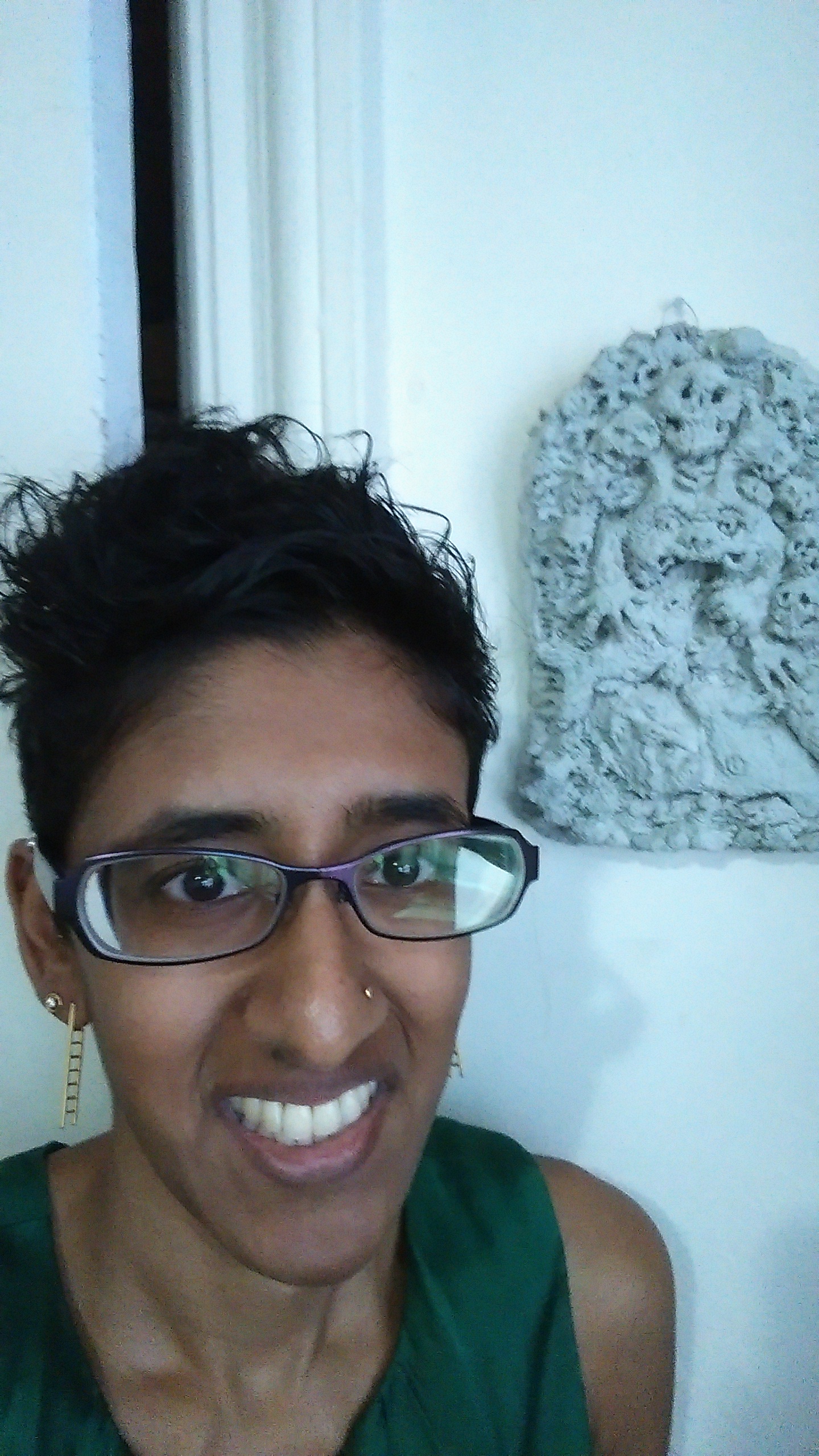

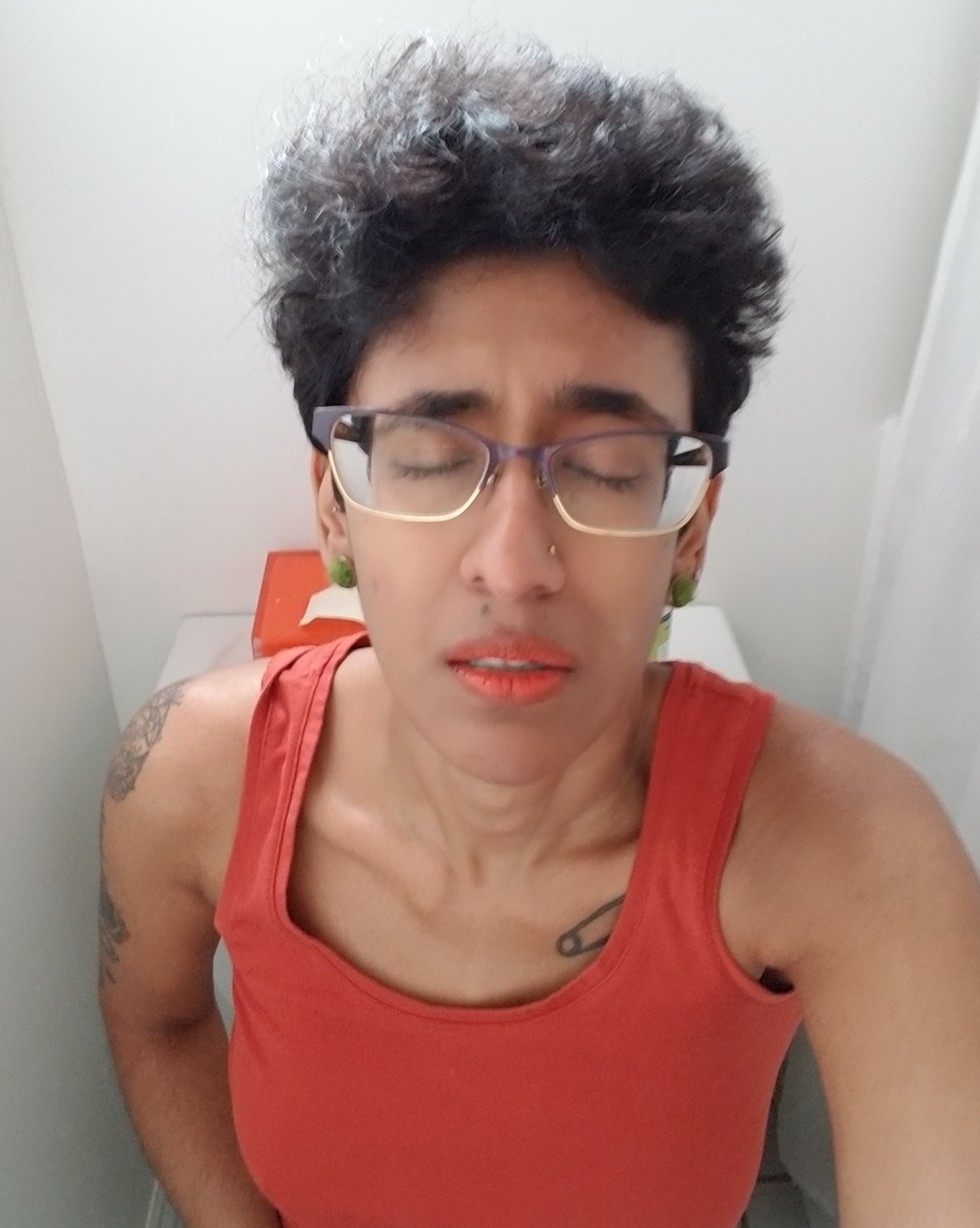

Because seeing is believing, I create a repository that lives on my phone, in case I need corroboration in the clinical or social encounter. However, there's a fine line between diligence and hypochondria, and not all of this evidence is limited to clinical use. Palatable photographs — the ones that align with bourgeois taste and decency — can be shared and circulated, giving rise to the potential for social action and community formation. I share cheerful selfies under the hashtag #DEHEM (Disabled Empowerment in Higher Education Month), looking for representation, though I am the only self-identifying Tamil and one of two self-identified South Asians. But preserving images of myself in states of infra-ordinary pain and fatigue as well as acute crisis feels more essential, because my verbal self-assessments have been interpreted as malingering without visual proof. Shared publicly on social media or with physicians on MyChart, photographs like these belong to a thriving archival economy by and for chronically ill patients, available for reference by nondisabled people and doctors.

This is how I — and many others with FMS and ME — look when you aren't looking.

(– 26. Biomedical Knowledge Production)

Physicians adopt medical jargon with me because I am fluent enough in their language to follow along, or I know too much and need to be reminded that I am not their equal. When a doctor tells me that sudden epistaxis (instead of nosebleeds) is hardly a signifying symptom, even though it can accompany autoimmune and connective tissue disorders, he's doing the latter. My hypervigilance about my constellation of symptoms communicates to him that I'm a hysterical, hypochondriac woman, and it's his duty as a white man doctor to calm me down (Greenhalgh, 2001; Barker, 2005). His jargon implies I am in expert hands. Epistaxis becomes just another bodily glitch to shrug off. Blood is supposed to be something one never gets used to — a brain smell, invoking violence, injury, and pain — but blood makes me trustworthy when I'm not intentionally spilling it. I woke up like this and took this photograph before washing my face and pillowcase. I can't bleed on command every time my pain is misbelieved, but I can at least show this image as proof of epistaxis. "All physical knowledge bleeds" (Ceronetti, 1993, p. 111).

Stoicism in a non-apparently painervated patient is a recipe for misbelief, but academic culture is arguably characterized by the presence of a self-inflicted chronic pain that must be conquered as evidence of scholarly, writerly capability. This chronic pain is configured as the consequence of neoliberal productivity: repetitive strain injury (RSI), carpal tunnel syndrome, posterior cervical dorsal syndrome, disc injuries. Domesticating pain is an implicit part of the academic enterprise. Posture becomes pathologized; ergonomic technology is touted as a means of conquering pain. Academia is detrimentally preoccupied with the disappearance of bodies, particularly non-normative ones, but endurance is an embodied phenomenon. Academic culture tries to frame physiologies of composition — and their physical and financial costs — as the consequence of nurturing "the life of the mind." It's an accepted fact that typing causes RSIs, but the fibromyalgic inability to cope with that pain signals an inadequate writer, too yoked to her corporeality to commit to the immersive focus required of scholarly research. By contrast, accommodating computer-related pains and injuries is configured as the mind's triumph over the body, stamped as scholarly aptitude, in keeping with the American frontier mentality and Puritan ethos (Hensley Owens & Ittersum, 2013; Selznick, 2017; Halttunen, 1995, Chen, 2014).

When I have a deadline, I'm expected to force my bodymind to meet it by using multiple ergonomic devices that mask my pain long enough for me to get the job done. This is one such device: one loop of Scotch tape between the second and third knuckle, shifting pressure transfer, accepting that each keystroke, even on a light touch chiclet keyboard, is injury. Scotch tape is infra-ordinary and endotic, and in my life, so are splints, braces, and support harnesses (Perec, 1973). I need prosthetics to complete the work of an ordinary day. I can pretend it's because I'm committed to the writing endeavor, not because I can't ignore my flesh.

A listed and reported side effect of Lyrica is ptosis, the abnormal lowering of the upper eyelid. You can see it here, though I was fairly well rested, the smoothness of the left eyelid, not even open enough for a crease, lips slightly parted in the struggle to keep it as open as it is. My glasses mask it to a certain degree, but too often a student or colleague says, "You look dead today," or "Are you falling asleep?" My ophthalmologist, who only believed me after I showed him this photo, suggested I do exercises to strengthen my eyelids several times daily: closing my eyes, squeezing them shut, opening them wide, holding them wide, blinking as normal. I lose interest in this endeavor fast. It exemplifies balut theory: a seemingly small expenditure of energy that fuels one thing and drains something else.

This series of selfies positions the spectator as a witness to pain, engaging with each image in an intersubjective, affective dynamic with the photographed subject. Padfield (2011, 2020) and Padfield et al. (2018) suggest that visual representations help generate empathy in the encounter between chronically pained and nondisabled individuals. Tagg (1988) and Padfield (2020) reminds us that the photographic medium conveys authenticity (despite the ease of digital manipulation), and so photographs of pain provide polysemic reference points for the fibromyalgic patient's subjective experiences (p. 97). These photographs also capture inconsistencies that aren't measured on five-point Likert scales. On the Difficulty doing daily activities section of the patient questionnaire, I truthfully check 1: Without any difficulty or 2: With some difficulty, because an atomistic approach to the body asks me to evaluate my pains comparatively. With my fluctuating pain, the events of this particular Wednesday aren't uncommon. I wake up well enough to successfully put on a button-down shirt, only to discover when I have to change for Pilates that I can't easily remove it.

My misabled instinct to self-document directed me to photograph myself, but when I scrutinize the image now, something looks staged. The dry-eyed grimace. The lightly creased brow. The bad camera angle that obscures the arthritic fingers. Despite Padfield's (2020) assertion, I think the digital age has cultivated skepticism in everyone. What can be believed? Nonwhite women's pain, without a bloodletting, so rarely is.

Then again, maybe I resort to an overly critical eye because memory overwhelms. The panic knotting my diaphragm. The rough, cold bathroom tile on my cheek when I lie down on the dirty floor, like I can draw energy from the ground, or conserve energy through horizontality. Button by button, with fingers that feel badly taxidermied, I get the job done. In some ways, what's important about my selfies remains everything that isn't pictured.

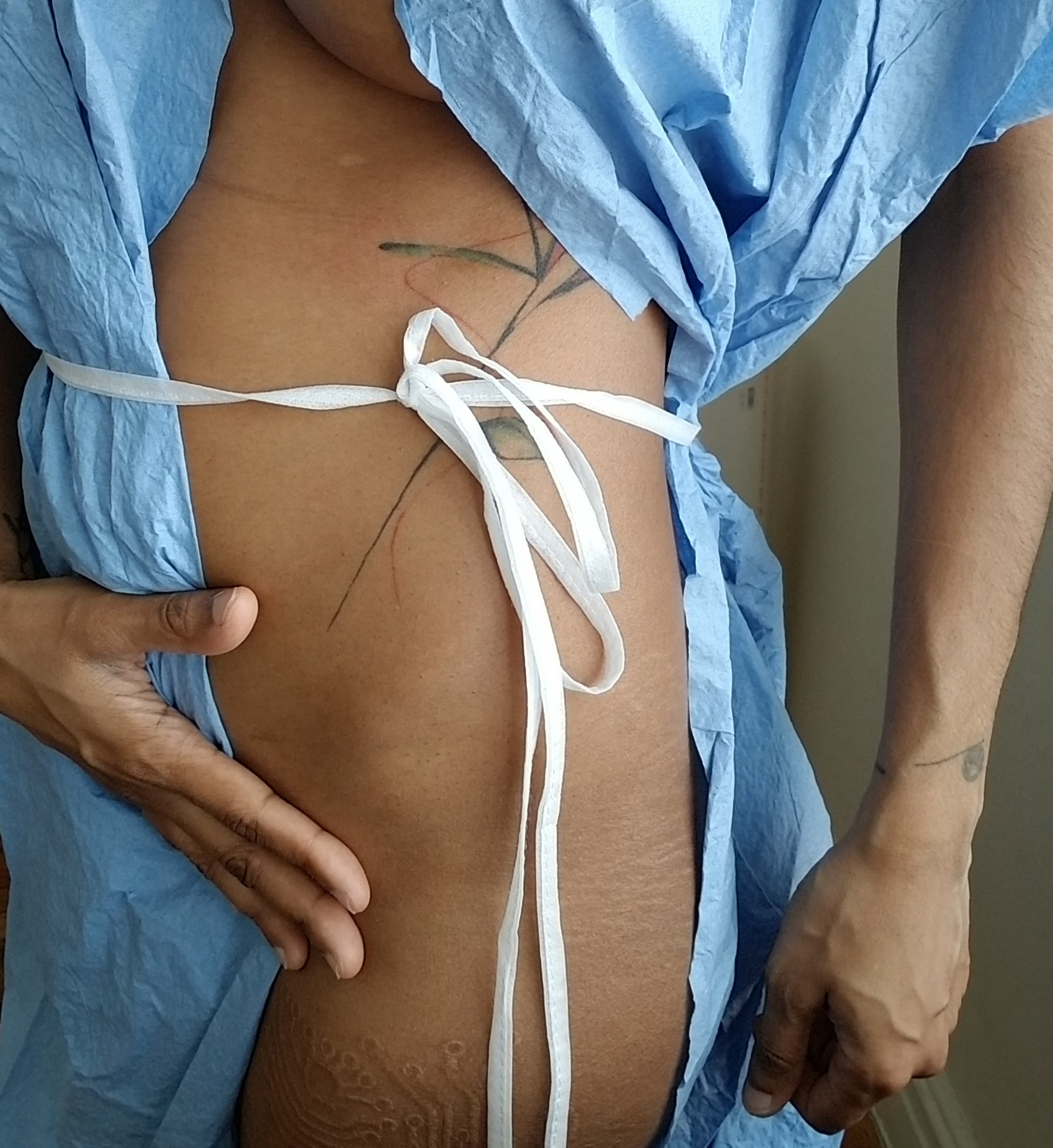

This is my final conscious pose on the operating table. I remember thinking it could be the last time I consciously positioned my body. I'd already given thought to the question, What happens if I don't wake up? I'd drafted a will on my phone. I'd taken out all my piercings except for the rook, which I couldn't unscrew. Dr. Sattva told me I'd be grounded for cautery, but it was still possible my ear cartilage would burn, and I replied, "Oh yeah, that's my biggest concern," and we laughed while I signed the waiver of liability for my ear, for interior relandscaping, for adhesions, for death. In the operating theater, I craned my neck to watch the anesthesiologist pierce my outstretched arm with the IV line. Sedation set in. A nurse removed my glasses and the world blurred further. The ensuing blackout was impenetrable. No sensation, no dreams, no perception of time. When I woke up it was, tritely enough, widespread pain that indicated I was still alive.

A psychologist told me that inhabiting these poses could help me safely process my medical trauma. Baer (2005) says: "I read the photograph not as the parceling-out and preservation of time but as an access to another kind of experience that is explosive, instantaneous, distinct — a chance to see in a photograph not narrative, not history, but possibly trauma" (p. 6). Traumatic time contains the unremembered event that the body can't forget.

This photo proves nothing to clinicians, but in social spheres it has all the signifiers I need.

The illusion of normalcy is a strategy for survival: I styled my hair, put on earrings, wore my thrifted green satin Tory Burch blouse, and grinned widely to downplay my creeping sense of impending doom. Still, you can see how much weight I'd lost by the narrowness of my face; you can measure my disorientation in the glassiness of my eyes. I had subsisted on coconut water and protein shakes for a month, the only food I seemed able to process, and I'd dropped about 15 pounds I couldn't afford to lose. Prior to my ER visit, before I knew what was wrong, I took this photo at the request of a friend who was trying to convince me that I wasn't really all there.

Peyththai that I'd become, I don't remember this specific moment. So much of 2014 is a mystery. Who was I pretending for? What did I hope the click would record for the requester? The wellness everyone wanted from me? The illness no one believed? These photographs "capture the shrapnel of traumatic time. They confront us with the possibility that time consists of singular bursts and explosions and that the continuity of time-as-river is another myth" (Baer, 2005, p. 7). There is a disjunction between seeing and knowing. The moment is captured, but vision does not give you access. Death stands in the background as I struggle to imitate life.

That I've survived something hasn't caught up to me yet. I remember feeling grateful while I posed for this selfie. I was still processing the medical trauma I'd suffered at the hands of Mitch, Dr. Tamas, and other emergency department physicians. Afraid of being fired, I was numbly conforming to the politics of precarity in neoliberal academia, commuting and teaching after one week of bed rest despite Dr. Sattva estimating three months of recuperation. This selfie is proof to friends and family that I'm better, like Charcot's tableau clinique in his image-driven analyses of hysteria, intended to exteriorize and fix the hysterical symptom. He (and so many today) believed the photograph could isolate reality from women's malingering. In Baer's (2005) words:

While photography promised to rein in the hysterics' histrionics, their affinity for masks and make-up marked them as prime candidates for the photographic collection. Ultimately, Charcot's gallery reveals that he sought to exorcise some of his own demons by pointing the camera at those twisting, panting, and hallucinating wild-haired female bodies. Did they really suffer, or were they putting him on? Indeed, is it not the doctor who suffers the hysterics' charades — suffers them as a threat to his authority, his mastery, his grasp of the truth? (p. 31).

Medical expertise inaccurately applied makes for anxious physicians, and anxious physicians are wont to sneer. I photograph myself in pain as a response to "photography's affinity with investigative thought" (Baer, 2005, p. 42) as it pertains to the field of medicine. My private archive proves the existence of my non-apparent chronic pain if my doctor can't discern it in the clinical encounter.

On 9/19/14 at 4:56 pm, the inflammatory adhesion from appendix to TI [terminal ileum] is scraped apart, and my appendix is removed through the navel and sent to pathology. Cutting through the firm segment of rectosigmoid tethered to uterus is deemed too risky a maneuver to attempt. The umbilical incision is closed with electrocautery, dissolvable stitches, and adhesive dressings; the suprapubic port incision (where the camera was likely inserted) and the trocar incision in the lower-left abdominal quadrant — neither pictured here — are similarly sealed. In the discharge notes, the wound type is described as clean contaminated, sealed through primary closure.

These scars are small. They belie the taut mountain range of scar tissue palpable under the skin. Surgery, after all, violates multiple layers of anatomy. But as van Dijck (2005) observes, "expectations of a healthy and modifiable interior rise proportionally to expectations of a mint and untainted exterior" (p. 81). Ultimately, my suprapubic scar is concealed by pubic hair; the trocar incision becomes a negligible discoloration; the umbilical scar, once the glue falls out and the sutures are removed, shrinks to a small white pucker. You'd never know from the surface that these places were once breached by cannula and camera. Combined medical-media technologies like laparoscopic surgery leave the skin virtually untouched, reconfiguring it as an easily bypassed barrier. The abdominal interior, filtered through media convention, becomes an aesthetic-corporeal space, where surgical technology can cleanly remove corporeal imperfections and leave the body aesthetically and medically untainted.

Consequently, the tyranny of ocularcentrism pursues me in medical visits with GI and OB/GYN specialists. I insist there is pain in my surgical scar tissue and am disregarded because the scars are so neat and tiny; they're barely there.

The glue was there. The pain is there. This photo is the fleshy reminder.

These selfies testify to private experiences before a public audience, attempting to close the cognitive and emotional distance between how I must inhabit my body and how you inhabit yours. Sontag (2003) says, "It seems that the appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked" (p. 33). Here is one that is nearly both. Just the provocation: Can you look at this? There is the satisfaction of being able to look without repulsion or arousal. There is the pleasure of recognizing that it is not you. Whatever fault lines lie below that small scar, most nondisabled people don't have them. I have learned to cup my abdomen, like so, as a makeshift splint against every cough and sneeze that tautens this hip-to-hip tightrope. I'm in pain, but the pose is gendered, almost flirtatious. Likely because I'm a woman, Dr. Sattva says, like it's a comfort, that laparoscopic surgery will spare me the unsightly scars. The navel port is nearly invisible, the suprapubic keyhole low enough that pubic hair conceals it through all but the most thorough depilation. In the end, it's more comforting to the male gaze, which desires nudity untainted by signifiers of pain or mortality.

The photograph arrests the elusive mark before it fades with time into time, ensuring the unending visible presence of what would otherwise be lost to time. This was, once is the photograph's testimony about time (Barthes, 1980/1981; Baer, 2005). Blink and you might lose it, this small visual signifier of abdominal scarring. Its suprapubic twin is just as minute, but white and stark amidst hair follicles and darker skin. Clinicians admire how neatly the incisions healed, but I feel the monstrosity underneath, pushed up to the edges of skin, mountain peaks during flare-ups, menstrual bloating, and ordinary digestion. The Ivory Tower and biomedical complex both run on micro-negotiations of power, from Ph.D. supervision to discussions with rheumatologists about the validity of fibromyalgia. When these two scars fully disappear, I will no longer have visible proof of this appendectomy. Dr. Sattva didn't understand that scars are visual cues I need. Their minorness competes against any assertions I make. Lose them, and the next time I claim this pain, the physician will shrug me off.

Demala sanniya, Sinhalese for demon of Tamil, is one of the masks in a Sinhalese devil dance ritual, Daha Ata Sanniya, meant to exorcise disease. In this folk taxonomy, the category of disease to which Tamil belongs includes pallor, vomiting, loose stool, and is related to madness and bodily contortions (Thilakarathne, 2018). With my appendix removed, some of the symptoms represented in demala sanniya — pallor, nausea, diarrhea — cease, but the bowel pain remains.

Wilson (2015) proposes the gut as the location of the second brain, contending that the stomach is intrinsic to mind and comprises a nervous system dispersed across the enteric, neurological, and microbial (p. 14). Gut feelings are the feminine cunning of the goddess Metis devoured by Zeus; so what are gut bacteria, which have material agency over how we occupy space and time? Kalin and Gruber (2018) see the gut as an environment, an organ that insists on sensual inquiry and affective entanglements with the microbiota it contains. The gut makes and remakes the body through our interactions with probiotics, prebiotics, antibiotics, food. Microbiota play a role in composing the body-in-neuropathic/visceral pain, as affect states like stress, depression, and pain are calibrated through millions of microbes that naturally occur, are introduced through diet and supplementation, are lower in abundance, or are missing (p. 273). With its altered microbiome composition, a body with FMS or ME inherently presents a different microbiome composition and alternate gut rhetorics. For instance, I'm told by a nutritionist in 2007 that F. prausnitzii, which produces butyrate — a short-chain fatty acid that controls for leaky gut and inflammation and has anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects — is often lower in fibromyalgics. Other butyrate producers might be lower in ME patients but higher in those with FMS.

The dominant theory of appendix function is that it houses good bacteria that repopulate the digestive system when the gut is overwhelmed by illness. In the autoimmune-disordered body, what does it mean if the safe house promotes its own infection? What happens when the corrupted refuge is excised? Millions of people undergo this procedure and emerge unaffected. Post-surgery, I have to eat as though I have a stricture, taking care with portion size and forms of fiber to avoid creating bulk, to reduce the twisting, crawling sensation of digestion through the lower third of my abdomen. This further changes the affective entanglements of my bodymind and my millions of microflora. Frequent snacking can contribute to leaky gut syndrome, where intestinal junctions are looser than usual, permitting microbes and particles to pass through. Butyrate is produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary soluble fiber. Nutritionists tell me there's no help for it; if I want to improve my health, I must recompose my gut rhetorics by consuming my torturers. This is the result.

Bowel pain is the subject of closed doors and held breaths. Here, for all the misbelievers, is the scene behind those closed doors, the frozen painervated subject captured in a slice of time both fragmentary and eternal, haunted by visceral agony scratching from within.

Skin is an organ of communication, a vehicle and receptor of touch, a canvas for visible signifiers of pain. To extrapolate from Didi-Huberman (2008), photography crystallizes the link between the fantasy of pain and the fantasy of knowledge (p. xi). If the event of pain demands that visibility precede belief, then this commonplace bruise is both spectacle and signifier.

The more I reimage and reimagine myself as spectacular pain, what new ills or manifestations do I summon forth in myself, or suggest to others? Bruises are ordinary enough. This one might signify a rough encounter with a table or underlying vascular problems. The photograph doesn't depict how a compression sock donned incorrectly throttled my calf into this color, or that compression socks were prescribed because hypotension fuels my brain fog. Regardless of the cause, it hurts like a snapped bone.

Without visually identifying the cause, what does the photograph conjure for viewers? Because bruises are universal, does it surface my painervated reality? Or for the same reasons, by displaying a bruise as a common, livable phenomenon for my fibromyalgic uyirmey, do I make it even easier to dismiss?

The photo is out-of-focus because I was drunk on Stolichnaya, shaky from pain and bloodletting, exhilarated at the results of my excavation. I'd undergone podiatric surgery for a plantar wart a half-inch in diameter, so vascularized that it bled liberally at a single prick. Insurance deemed the surgery elective. I paid hundreds of dollars out of pocket for the podiatrist to remove it with a scalpel and a laser, but he must not have cut deep enough, because like a horror film monster's eternal return, the creature grew back. Already drowning in the medical costs of seeking a diagnosis, I couldn't afford another surgery. So I assembled a razor, a lighter, OTC liquid nitrogen, rubbing alcohol, gauze, and vodka; I took shots to dull the pain and scraped, froze, and cauterized my toe until the wart was no longer visible or palpable. I'd been experiencing full-body nomadic pain for months, so this acute, localized pain, an alarm with a purpose, was a relief.

Perhaps this was the moment I should have realized something was wrong.

Later this same year, when I'm diagnosed with fibromyalgia, one of the first questions Dr. Birnbaum asks me is if I recently had the flu or underwent a surgery. When I mention the wart, she says it could be read as a sign: warts themselves can be harbingers of a weakened immune system, and the surgery might have worsened central sensitization. Her focus, though, is the musculoskeletal system and gut. She doesn't run the battery of tests associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis, even though she unofficially diagnoses me with chronic fatigue, too. In 2020, 13 years later, I find out I have elevated levels of HHV-6 antibodies. This blurry image of debrided flesh from 2007 is the only photo I have of this possible cause of reactivation.

Misability is being too "high functioning" to always require mobility aids, but too weak to lug around all the potentially necessary equipment. You learn to perceive assistive aids in everything. There's something fundamentally tricky in this, to extrapolate from Hyde (2010), who emphasizes the adaptability of the boundary-crossing trickster figure, both in word and action. Like Hermes, inventing the lyre from a tortoise shell, or boy-Krishna, caught with his hands in the butter urn and ghee smeared over his face, slyly telling his angry mother Yasoda, "I stole no butter, Amma; does not everything in our house belong to us?" His lie upsets our webs of signification, altering our sense of what can be true and false.

My existence is adaptive and disruptive, redefining pain and methods of research and writing. I heard rumors in my first year that I was admitted to my doctoral program as a wild card, a kind of potential academic subject that did not yet exist among our Ph.D.s, an institutional investment in radical interdisciplinarity, creativity, innovation, or lipservice to the university's mission. I was such a misfit that, three years in, the expectation was that I'd drop out. The institution communicates its expectations, imbuing the (academic, clinical) subject with the obligation to meet them, but misability has mutated my pathways too much. Once upon a time, I was able to spoon-feed these connections to you in all the generic forms you need to understand. Today, let this be evidence that, at work, clandestinely between classes, I suffer.

In the academy everyone is suffering, and they wear their suffering with pride. We call every bodily state stress. Unlike fibromyalgia, this is a badge of distinction, a rite of passage. Professors and colleagues chat cavalierly about sleepless nights, too much caffeine. I am denied this common experience. Too little sleep on my medication, and I become dysphasic. Too much coffee, and the scar tissue in my gut is like pulverized glass. Classmates have overheard me screaming in the third-floor bathroom at Rutgers SC&I before I teach class, but no one asks me why. My pain is too real, not a badge of honor.

Pain wears all its civilized disguises in the academy, as sterile as the clinic in its pursuit of knowledge. As Leder (1990) notes, even

a chronic pain for which one has no solution continues to grab the attention with undiminished intensity. To an extent, one can accept or become accustomed to such pain. But it still retains something of an episodic character. It is as if the pain were ever born anew, although nothing whatsoever has changed. (p. 73)

When I try to articulate it, everyone hurries to remind me, "Oh, well, you look great, though!" When I wryly mention to colleagues that I vomit from pain while writing papers about pain (oh the irony), I kill the mood. No one knows what to say, or how to suggest I don't have what it takes to be an academic, that I don't belong here. That pain is private, shameful, barbaric (Halttunen, 1995; Abruzzo, 2011). Nothing left to say but thanks.

Like Lau (2020), I too

have tried to crip my writing process towards a more compassionate invitation of pain into the precarious act of communicating ideas and experiences. A process that does not shy away from pain's presence but is in fact constituted by pain and its vagaries. This, to me, is what a truly crip form does: poetry or prose that models the work of cohabitation with disability and chronic illness as kin. (para. 3)

Your exclusions are never clearer to me than in the language you ask me to use.

Why did I photograph these eggs? Probably to support a request for a refund credit from my grocery delivery service, but also, some other misabled curatorial instinct whispered: Keep this. Trying to figure it out today, I look for patterns as always. Four months after the appendectomy, was I fond of saying that my gut felt like this, an egg broken in a blocked ovipositor futilely squeezing to make life? Did I think it could be an Americanized gesture at balut theory, this vandalized fragile house, the inhabitant brained with bits of shell? Did I feel a sudden tenderness for the thing I was about to discard, in memoriam of my excised lymph nodes or appendix? Or did I recognize myself, all the ways I embody patienthood, the successes and failures of daily survival?

Ahmed (2017) says, "We might inherit a break because it was survived. A survival can be how we are haunted by a break" (p. 192).

Theorists like Benjamin, Barthes, Bazin, and Baer have all written about life and death and photography's temporal paradox, its capturing of the past and present, its disastrous knowledge that the photographed subject is simultaneously still real and imminently dead. The eye registers the lasting trace of presence even while comprehending absence. These photos arrest the body, dying of a ruptured appendix, sapped by HHV-6's commensalism, its resulting fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. These photos avert the possibility of death by fixing the body in a moment in time, death is always hovering in the margins. How the body is haunted by a break. These photos say to doubting physicians, Whatever is presented to you today, look, here, and understand how much feels broken.