106. Divine Panopticism

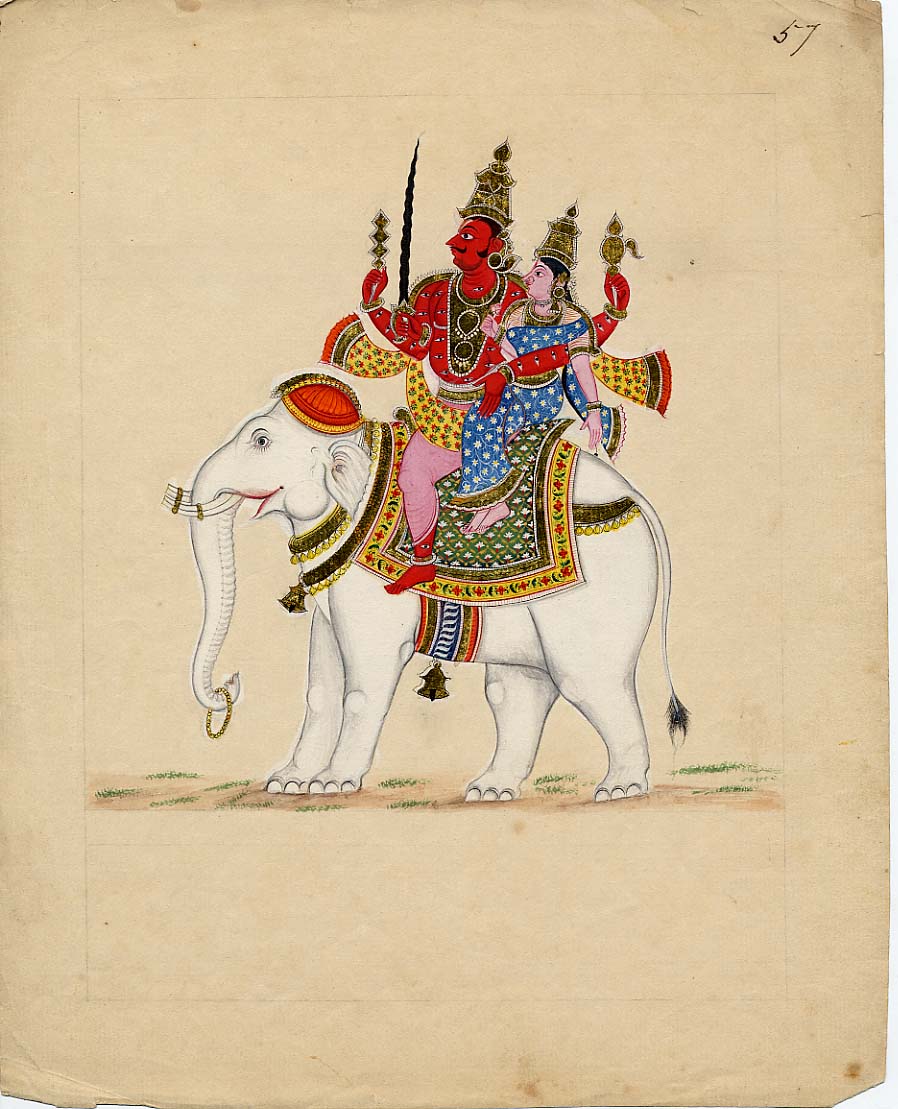

The god Indra is the ruler of the heavens in Tamil mythology. Indra is a more ancient, inexact analog to Zeus: he is similarly lusty, but his power over the heavens and earth is not so consolidated; powerful rakshasas and irascible sages have threatened his rule; he is as all-seeing as metieta (wise counselor) Zeus, but not because he swallowed a cunning primordial goddess. A softened curse freckles Indra's body with a thousand eyes that never close all at once. In this respect, he is less like Zeus and more like the minor figure Argus Panoptes, the ever-watchful, many-eyed giant charged by Hera with keeping Zeus away from the transformed nymph Io. The eyespots on a peacock's tail were thought to be Argus, immortalized; the peacock is sacred to Indra, who disguised himself as one to hide from nigh-invincible Ravana on a mission of conquest, the thousand eyes of his body translated into the bird's tailfeathers.

Still, in both pantheons, each divine kings acquires his hypervigilance because of a woman. Zeus consumes his consort Metis, a goddess of legendary cunning, who leaves no physical mark. Divine surveillance becomes physically inscribed on Indra's body as an indirect result of him fucking the sage Gautama's wife, Ahalya, a woman of unparalleled beauty.

In many South Asian stories, mortal sages are often as strong as the gods and quick to anger, and gods in their divine forms or avatars are like trickster figures falling prey to their own snares. Besotted with Ahalya, incautious Indra assumes Gautama's likeness and seduces her. However, Gautauma catches him leaving and curses him to lose his penis and testicles and to be covered in a thousand yoni (vulvae), so that mortals, devas (gods), and asuras (enemies of the gods) alike could perceive his lustful nature.

Ashamed, Indra hides himself in a cave, until Brahma urges him to perform tapasya (austere spiritual meditation) to appease Gautauma. After doing so, Indra's absent manhood is restored with the parts of a ram, and the vulvae are transformed into all-seeing eyes. And so Indra becomes known as Sahasra Aksha, Thousand-Eyed. Like the Foucauldian eye(s) of power that discipline and monitor individuals in an (androcentric) visual regime that produces patients, students, professors, prisoners (Foucault, 1963/1994).

That these eyes derive from vulvae represents feminine foresight. Seducing Ahalya ultimately gives Indra this foresight, but the woman herself, unable to distinguish between her husband and a tricky god's disguise, is also cursed by Gautama for succumbing to carnal desires. It doesn't matter that it's not really her fault. By his utterance — "You will tarry here for thousands of years without food and consuming air alone, and unseen by all things you will live on, contrite in the dust, until Rama arrives at this hermitage and purifies you" — she is made to exist, as it were, as an aavi (ஆவி).

In this telling, the hypervigilance of panoptic vision inheres in the feminine principle, born from the genesis of a ghostbody.

When I heard this as a child, it registered as injustice. Now, as a chronically ill academic, I hear it the same way I hear Haraway's (1988) question: "With whose blood were my eyes crafted?" (p. 581). I am no Ahalya, but how many men played a "god trick" on me, plumbing my interior with their objective cameras and biomarker tests? Producing nothing legible to these gods, I become invisible in the clinic; disclosing in school, I am socially invisible for all the ways I don't fit in. Divine surveillance justifying itself by disciplining and disappearing the feminine transgression that necessitated and created it. And yet, though Ahalya waits a long time, socially ostracized and sustained only by air, she is eventually redeemed, while Indra's body forever bears the indelible evidence. Metis stays politely contained in Zeus' nēdús(gut or womb), but you need only run your hands over Indra's glorious skin to tell how each eyelid is one half of a pair of lips.

(– 66. Expanding the Dimensions of Metis)