25. Gatekeepers of Pain

Modern biomedicine rejects musculoskeletal origin theories of fibromyalgic pain, but fibromyalgia syndrome belongs to the field of rheumatology given the muscle and joint pain that sufferers experience. Rheumatology as a field of specialized professional medical expertise is more capacious than most medical fields. The common conditions it enfolds, such as arthropathies, lupus, tendonitis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Sjögren's syndrome, myofascial pain, and fibromyalgia, are dissimilar, chronic, poorly understood, and incurable, and can't be termed musculoskeletal disorders with any sort of neat precision (Barker, 2005, p. 19). A medical condition is perhaps only as legitimate as the clinical specialty to which it belongs, but what other field would even tentatively accept fibromyalgia? Dr. John Bonica, author of the groundbreaking medical textbook Management of pain (1953) and a chronic pain sufferer himself, tellingly observes in a 1989 interview, "No medical school has a pain curriculum" (qtd. in Morris, 1991, p. 22). According to Barker (2005), "Although pain stands at the margins of biomedicine, it stands at the center of rheumatology. In effect, pain has become the conceptual justification for rheumatology" (p. 19).

Significantly, this negatively affects the conceptual jurisdiction of rheumatology as a professional field of expertise, as — unlike other fields — pain is "a medical object distinct from those that can be directly read from the body or discovered through laboratory tests" (Baszanger, 1998, p. 8). Evidence-based medicine grounds clinical decision-making in scientific research, such that clinical trials and biostatistics continuously reconfigure diagnostic procedures, types and validity of treatments, symptomology, and standardization of pain (Berg & Mol, 1998). This diffuses into social practices, including how the public views medical authority, how lay expertise is viewed, and how patient identities — perhaps especially in the absence of evidence, as with fibromyalgia — get defined and assigned. Furthermore, "the cultural weight assigned to the notion of evidence in medical discourse goes well beyond what evidence does in actual medical practice, extending into matters of power, prestige, and economic dominance" (Derkatch, 2016, p. 28). I stand at the center of jurisdictional disputes, arising from each new specialist claiming territory already staked by a previous or coinciding one.

As the gatekeepers of autoimmune disorders and pain syndromes, rheumatologists ultimately determine my medical destiny. I begin with a nurse practitioner at Columbia University, Nancy, my primary care provider at the time. I am experiencing widespread nomadic pain, brain fog, exhaustion, an inability to stand, an unsteady gait, trigeminal neuralgia, visual snow, increased pain during already painful periods, zero libido, sensations ranging from formication to a machete dragged slowly across my throat. When I'm well enough to attend class, I wear scarves like a preemptive bandage to remind myself that it's just a somatic sensation. I have a constant fear that I will, crazed by pain, stab myself in a counterintuitive attempt to rid myself of it. I am an itinerant patient in the fields of psychiatry (to rule out depression, anxiety, adult-onset schizophrenia), neurology (to rule out strokes, brain cancer, Chiari malformation), ophthalmology (to rule out multiple sclerosis), cardiology (to rule out valve defects and heart disease), gynecology (to rule out endometriosis, ovarian cysts), gastroenterology (to rule out pancreatitis, ulcerative colitis, IBS), orthopedics with an emphasis on the hand and wrist, and rheumatology. The neurologist I saw suggests a tumor before imaging was even done. Dr. Anderson, a hand specialist, tells me I'm too young for this pain, and a better ergonomic setup will cure me. After my rheumatologist Dr. Birnbaum officially calls it fibromyalgia, Dr. Anderson is skeptical, implies I've been misdiagnosed, asks who diagnosed me, and says he's never heard of her, like medical epistemic authority belongs to him alone. As for the gastroenterologist, he doesn't even bring me to his office.

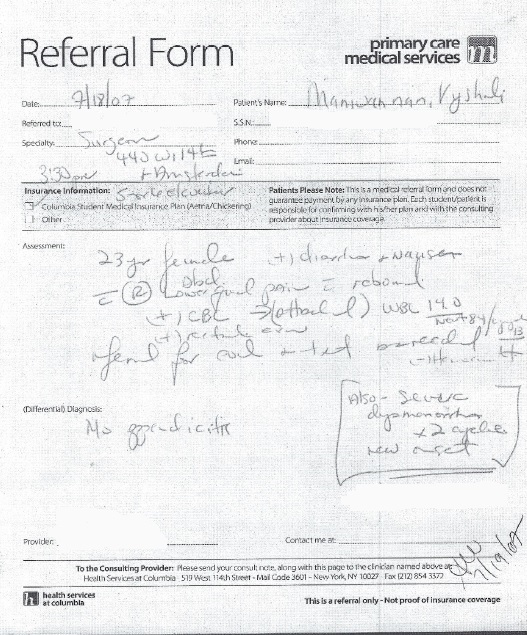

In retrospect, I wonder if my appendix had begun to perforate that day, when I doubled up, broke down, and begged Nancy for a referral. On the referral, she wrote down dysmenorrhea and appendicitis. Over the phone, I was instructed by the gastroenterologist's office to pack a bag in case of surgery and an inpatient stay. But the gastroenterologist merely swept into the waiting room, sized me up, asked where I felt pain, prodded me in the lower abdomen, and told me I was fine. He got on the elevator, and I went home and maxed out my daily dose of Advil.

These doctors are mostly white and mostly men, and men mostly don't believe women like me.

Physicians untrained in treating chronic pain may doubt their patients' subjective data, habitually prescribe inadequate medication doses for effective pain relief, resent the high rates of patient recidivism, and have trouble identifying chronic pain as anything other than a symptom (Morris, 1991; Baszanger, 1998). Medical curricula's avoidance of chronic pain, and the delegation of chronic pain to rheumatology, may also impact the length of time to diagnosis. On average, it takes five years and five specialists for a chronic pain sufferer to receive a diagnosis, according to AARDA (O'Rourke, 2013). In those five years, patients will be doubted and disbelieved in the clinic and the workplace; undergo the financial strain of medical bills and lab work; suffer the iatrogenic consequences of painful exams like dolorimetry or nerve conduction tests; be instructed to lose weight, exercise, sleep more, relax; be misdiagnosed; and go on and off medications in a trial-and-error process of treatment. They are likely to begin seeking treatment from a PCP outside of the field of rheumatology, where straightforward biomarkers like fluorescing in brain tissue on contrast MRIs or a high white blood cell count are foundational to diagnosis. When the tests come back negative, their PCP will refer them to a physician in the field they think is most likely to possess jurisdiction over the disorder, based on how they organize the patient's presenting symptoms. That is, if the PCP's medical education or practical experience leads them to prioritize headaches as a symptom, the first referral is likely to be to a neurologist. Moreover, specialties like neurology, long established and therefore credible, are more likely to attract initial referrals in the hopes of finding diagnosis or cure. The less likely it is that a solution exists, the more reluctant physicians may be to take the referral (Dickinson, 2016).

Rheumatology is the final stop on my diagnosis journey. I'm lucky that it only takes a little over a year for me to receive a diagnosis of FMS, but less lucky in that my ME and POTS are missed until 13 years later. Delays in diagnosing and treating pain and fatigue have long-term consequences for sufferers, as they have specific effects on the body. Chronic pain generates enduring physiological and psychological changes that can become permanent (Morris, 1991; Baszanger, 1998; Bourke, 2014). Furthermore, a lack of diagnosis and treatment plan contributes to stigma in the clinic and in the public eye, where, respectively, the patient can't occupy a medically or socially acceptable illness role (Nielsen, 2012). Studies have shown that chronic pain sufferers tend to feel that physicians and society doubt the reality of their pain in the absence of biomarkers that scientifically "prove" its existence. In addition to pain management, many patients want validation, and validity inheres in the blood, in names.

By Fall 2007, I have a name, but not of a credible condition, and not from a field with a clear conceptual paradigm. It's telling, then, that years later, Dr. Jiang classifies the disorder as "Other" on her patient intake form. ↩

(– 113. Samudra Manthana)