78. Ten-Headed, Many-Armed

Although there are words in Tamil for disability and disabled, when Amma describes a physical or psychiatric disability, she never uses these words; instead, she describes its constellation of symptoms. It makes for an inefficient exchange, but at the same time, such descriptions are necessarily individualized, like the approach to wound shock or railway spine. At its vaguest, it becomes an issue of functionality. Eylum or eylaathu. Can or can't.

Can't, though, proposes disability as deficit. Even Achilles and Odysseus can be understood as non-normative, if not outright disabled. Perhaps "the point is that when we really start looking, and resist the urge to dismiss disability, we recognize it everywhere" (Dolmage, 2014, p. 151), even in bodyminds that are heroic, symmetrical, and capable.

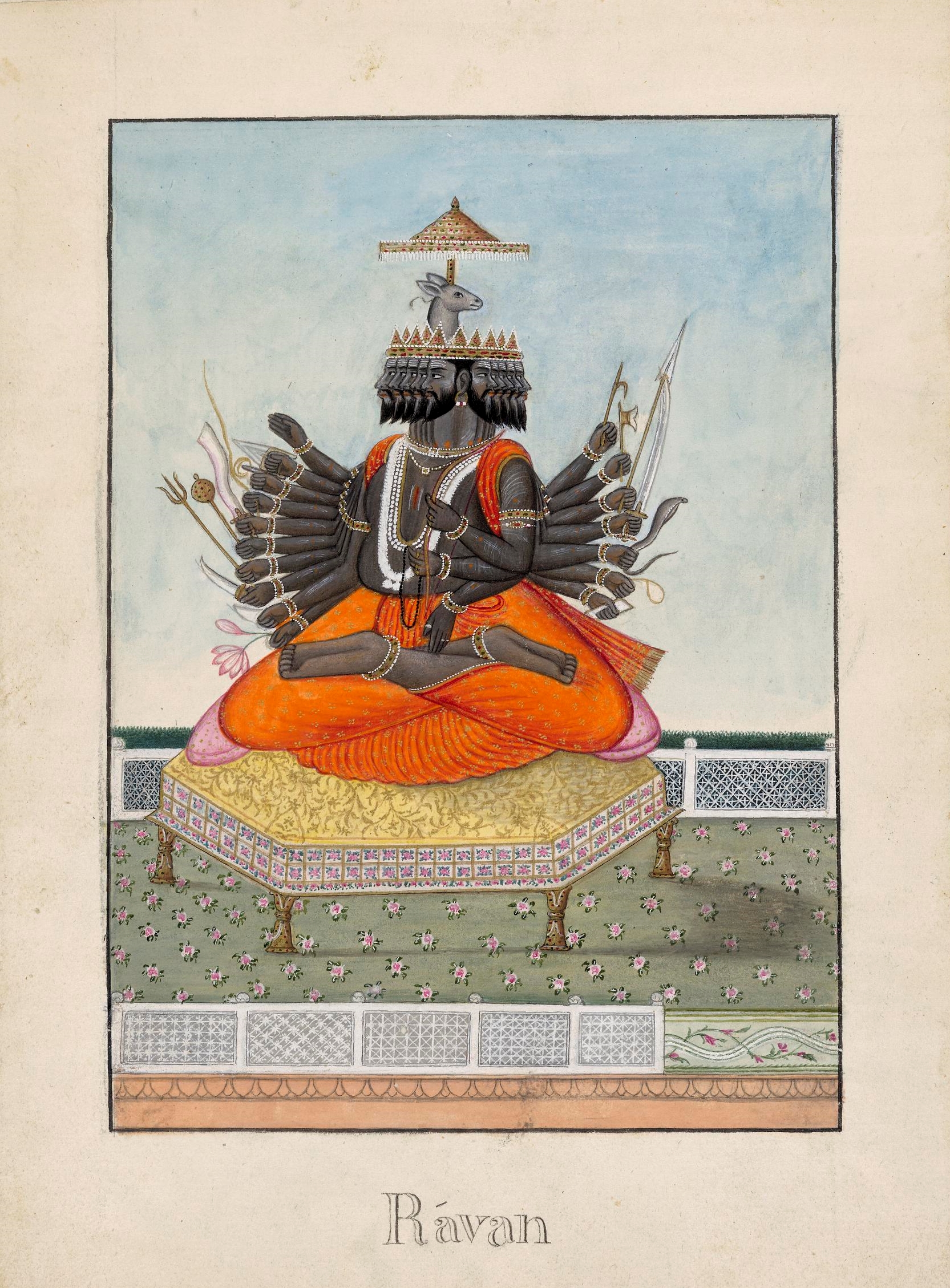

The rakshasa king Ravana is renowned for his 10 heads and 20 arms; notably, in some versions of this story, his 10 heads were not congenital but acquired. In those tellings, Ravana performed an intense tapasya to Shiva, decapitating himself 10 times, a new head regenerating each time to enable the continuance of his penance, until Shiva, pleased with his dedication, granted him 10 heads. It is said that these heads represent the six Sastras and four Vedas — mathematics, yoga, law, the physical sciences, philosophy, and the study of actions, and the Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samveda, and Atharvaveda — signifying his intelligence. His 20 arms indicate his sheer strength as a warrior. Ten-headed, many-armed is an epithet for Ravana in The Ramayana, the way that Homer applied swift-footed to Achilles. He is merely viththiyaasam, his bodily difference just a description.

In Valmiki's version, Ravana is born with 10 heads and 20 arms and performs austerities for Brahma to defeat his half-brother, Kubera, the physically deformed yaksha king of Lanka. When Brahma finally appears and offers a boon, Ravana asks for immortality but is denied because all that lives must die. So instead he asks, "O great Brahma, grant me invincibility from and supremacy over asuras, devas, yakshas, gandharvas, nagas, and rakshasas" — omitting humans from his list, as he did not consider them a threat.1 Brahma accedes to this request, and Ravana goes on to conquer Lanka.

Like Achilles, Vedic figures like Kubera, Karna, Ravana, and others like them embody difference as neither deficiency nor overcompensation, but as an infra-ordinary fact of the flesh. Kubera, meaning "ill-formed" in Sanskrit, is described as a fat, three-legged "dwarf" with eight teeth, but he is the god of wealth and a world protector with a seat in the high Himalayas. Due to his disability, Brahma asks Vishvakarma, presiding deity of craftsmen and divine architect of the gods, to build Kubera a chariot — the fabled Pushpaka Vimana, a capacious aerial chariot that moves of its own accord, fantastical forebear of the motorized wheelchair and a vehicle desired by many. Karna, born with kavach and kundal, potential signifiers of a congenital disability, becomes vulnerable only after he maims himself into a normative appearance by cutting them off at the disguised Indra's request. And though he could not have predicted Shiva's boon, Ravana earned his heads and arms, implying such difference is desirable.2

In a telling that isn't in Valmiki's Ramayana, Ravana is granted a pot of amrita that makes the possessor immortal, so he stores it in his navel; in the war in Lanka, he survives wounds and decapitations and dies only when Rama's astra pierces him there.

Weak-heeled Achilles, weak-bellied Ravana, neither were lesser for these traits. I computed these stories thus: physical difference, congenital or acquired, is immaterial; the world will enable you.

Turns out I was wrong.

Plenty of ancient myths inconsistently paint congenital, late-onset, or divinely inflicted conditions as impairments, augmentations, or infra-ordinary facts. Many of these figures are subject to disability tropes, especially the myth of overcoming or compensating for the disability through hard work or a special gift (Dolmage, 2014, pp. 35-46, 76). Tiresias, the blind seer, was extolled for his prophetic accuracy. Phoenix, cursed to blindness and impotence by his father, has the former reversed but not the latter, a limitation he transcends when he becomes mentor to Achilles and Patroclus. Hephaestus' mobility impairment does not bar him from membership in the Olympian pantheon and is overshadowed by his cunning.

In The Ramayana, the wicked maid Manthara, meaning hump-backed, convinces Queen Kaikeyi to exile Rama for 14 years so her son Bharata might reign. In the The Mahabharata, Dhritarashtra, congenitally blind, was trained to be a king while his younger brother Pandu was trained to be a warrior, but at his coronation, his capacity was contested: how could a blind man lead an empire? He is crowned as de facto king when Pandu abdicates. That Dhritarashtra's son Duryodhana is the epic's villain, his faults often blamed on his father's blindness, depicting the belief that sins are inherited.

At the same time, Manthara is as loyal and crafty as Medea, seeking only to secure the future of her mistress Kaikeyi's progeny. Dhritarashtra is a virile king who sired a hundred sons and a daughter and possessed the strength of 10,000 elephants. Duryodhana, "son of a blind man," resists contemporary class biases in crowning Karna and was a stalwart, generous friend (Kumari, 2019, p. 41). These figures are ambivalent, sometimes vilified, sometimes presented as compensating for their disabilities through intellectual ability, proofs of good moral character, or reproductive value (Dolmage, 2014).

Historically speaking, the prevailing assumption about disability in ancient societies is that disabled citizens were medically and socially undesirable and therefore expendable, through infanticide, exposure, or social ostracism. The prevalence of disability-related infanticide in ancient Greece relies primarily on literary accounts, which suggest that the ideal biological and political body could not suffer deviation. However, Sneed (2021) suggests these accounts reflect more about the authors' dispositions towards disability and infanticide, not actual ancient practice, and that the willingness of scholars to accept it says more about contemporary beliefs about (re)productivity in ancient subsistence agricultural societies. Cleft lips, polydactyly, club foot, and congenital and war-related mobility impairments, among other disorders, were common and unremarkable in the ancient world. Monarchs like Agesilaos II of Sparta, recognizably congenitally impaired in his legs, aren't described as impaired in character or ability to lead, and congenitally ugly girls could potentially "outgrow" their condition (pp. 751-753).3

Sneed (2020) contends that the unexceptional nature of these impairments suggests that somatic difference was recognized and accommodated. She notes that permanent ramps erected at healing temples made religious and clinical spaces broadly accessible (pp. 1016-1025). She also points to Hippocratic treatises and bioarchaeological evidence, like ceramic feeding bottles, as evidence of a society that actively accommodated and assisted disabled infants, such as those with orofacial anomalies (Sneed, 2021, pp. 748-749). The medical treatise On Joints characterizes congenital limb difference in terms of ability, physical therapy, and needed modifications, but it does not suggest that disabled infants aren't worth rearing or that they grow into unproductive adults (pp. 754-756). In fact, adult inhumations in the Athenian Agora from the Early Iron Age display evidence of degenerative joint disease, such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, indicating that disabled people were assisted and cared for. Literary and medical accounts describe assistive devices, from reinforced shoes to crutches to prosthetic limbs (Sneed, 2020).

Though ancient beliefs are evoked to justify modern attitudes, the two evaluations rarely match. There is a threshold of disability implicit in modern-day conversations about disability, about what lives are worth living and who should be euthanized, founded on ableist assessments of what counts as "disabled enough" (Sneed, 2021, p. 768).

In her examination of disability in the intersectional contexts of Indian society, Nair (2019) observes that, while caste, concealment, and marriage can mitigate the stigma of non-apparent chronic illness, revealing disability can result in suspicion, rejection, or abuse. Reproductivity takes the place of productivity: the disabled woman is a burden on her parents until she marries and becomes someone else's problem.

Tamil disability discourse in both the Sangam era and popular literature delineates three primary categories of disability: congenital, acquired, and social (Mangalam, 2020, p. 149). Disability is still often culturally understood as part of the cycle of samsara, karma manifesting in a polluted rebirth. In literature, it often carries tropes of punishment, as in a sage's curse or the fruits of karma; cunning, as in hunchbacked Manthara or limping Shakuni, whose craftiness spurred the conflict between the Pandavas and the Kauravas; compassion, charity, and piety, as in the virtuous Manimekalai feeding hungry disabled people; and bodily sacrifice that valorizes qualities of (vigilante) justice, as in The Silappathikaram's Kannagi (Mangalam, 2020).

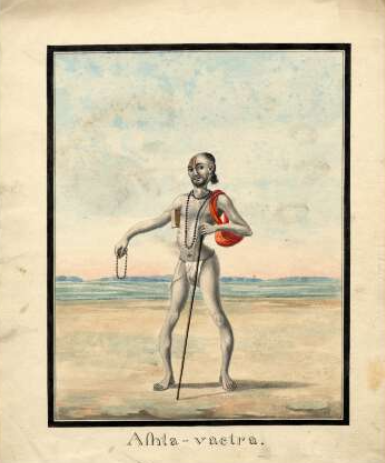

In the Vedic tradition, the great sage Ashtavakra, meaning eight bends, spans both the congenital and social categories of disability. The son of Vedic scholars, while he is still in utero, he hears his father Kahola inaccurately reciting the sastras to his mother, and he corrects his father from the womb. Angered, the proud Kahola curses him to be born with eight deformities (Kumari, 2019, p. 41). In another version, Kahola makes eight mistakes in his chanting, and Ashtavakra is so sensitive to these errors that his body develops anomalously in eight places. The father, interestingly, is responsible for his son's disability, not the mother.

Frighteningly astute, Ashtavakra learns the Vedas when he is but a child, and he travels with his father to the court of King Janaka, a scholar who often invited rishis to his kingdom to discuss and debate the meaning of the scriptures. After Kahola loses a debate, Ashtavakra wishes to make a rejoinder and is mocked for his appearance; however, he speaks so skillfully that he impresses the court, explaining that the shape of a temple does not affect its size or purpose and likewise the shape of his body does not affect Ātman. As The Bhagavad Gita does, he suggests that names and forms cloud our vision and chain us to maya, while the truly enlightened perceive only the Self and the oneness of existence. King Janaka recognizes his wisdom and bows before him, despite his deformity (Kumari, 2019, p. 41).

In spite of this inconsistent application of disability tropes, Narayan (2004) asserts that ancient India viewed disabled people as productive members of society — with many serving as rulers, teachers, philosophers, and artists. Evidence suggests that from 320 to 480 A.D., physically disabled people were given vocational training, and individual disabilities were treated as advantageous for certain social positions and jobs. Even though the epics don't describe how they lived, their stations were high and they were highly visible figures, such as the blind Vaishnava devotional poet Surdas (Narayan, 2004).

Davis (1995) suggests that the concept of disability only became an organizing principle in the 18th and 19th centuries, and words like "normal," "normalcy," "normality," "average," and their antonyms only appear in European languages around the late 1800s. We can date the cultural coming-into-consciousness of the "norm" in Euro-Western society to somewhere between 1840-1860. European normalcy is tightly coupled with industrialization, classism, binary gender roles, and the need for ideal working bodies. Through formal education, both word and concept enter British colonies that once regarded disability and difference as simply ordinary (p. 24).

In her research on blind identity in 18th century colonial India, Nair (2017) finds that "the colonial enumerations of disability began with the inclusion of infirmity as a discrete category in nineteenth-century British censuses; which marked the regular, recurrent and consistent attempt to identify and enumerate bodies and minds considered defective, 'unproductive' and subsequently dependent" (p. 185). This enumerative logic was critical in the construction of infirmity and impairment by the colonial state. Explanations of disability hinged on pathological and social factors that were steeped in racism, Orientalism, and white supremacy. Blindness in particular symbolized "the spiritual darkness of the subcontinent" (p. 199), necessitating missionary intervention. Disability was perceived as the "corporeal cost" of caste-related bigotry, "primitive" medicine, and "backward" superstitious beliefs (pp. 189-199). The high visibility of disabled mendicants was thought to "pollute" otherwise civilized British colonial cities. However, it is unlikely that this legibility impeded the participation in routine social life by the blind, lepers, or other disabled members of colonial South Asian society (p. 199).

Kumari (2019) and Nair (2017) suggest that karmic philosophy dominated social attitudes towards disability in ancient India: that is, it is good karma to care for paavam disabled people (Nair, 2017, p. 192).4 According to Mangalam (2020), "notions of pity and piety governed the representation and treatment of disability as a subject, image or mode of performative subjectivity" (p. 149) in Sangam literature, and those attitudes dominate today in Sri Lanka, though they are entangled with postcolonial geodisability discourses. In Sri Lanka, natural disasters — such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which smoothed out features of my parents' childhood in Batticaloa — and decades of ethnic conflict and genocide created a body politic inscribed with psychological, physical, and cognitive alteration. The social atmosphere in former warzones like the Vanni is described in apocalyptic or pathological terms. Sri Lankans disabled from the war, the tsunami, postwar incidents, or other accidents are heavily stigmatized. (For instance, disabled women are bad luck on long journeys or at weddings.) In the stories told by disabled Tamil and other ethnic minority women in Sri Lanka, social suffering is often described as more painful than the physical disability itself, as impairment leads to communal rejection, social exclusion, family conflict, and a lack of marriage prospects. This is perhaps especially true of Tamil female fighters, who were extolled as cadres but whose disabilities now mark them as ex-LTTE and thus a dangerous presence in communal, government-surveilled life (Kandasamy et al., 2017, pp. 48-50).

Factors overlooked in Global North discourses — such as marriageability, caste, gender performance, and signifiers of war — co-construct the perception of disability (Nair, 2019). Disabled Tamil women in Sri Lanka today experience "triple discrimination" due to family dynamics, income disparity, and social stereotypes, and their advocacy necessarily transpires under the aegis of postwar reconciliation, peace, and justice (Kandasamy et al., 2017, pp. 52, 56). Policies that attempt to universalize standards and norms of disability, as with the United Nations or World Health Organization, delimit and denote "kinds of bodies known as disabled. . . . an outlaw ontology which nuisances the seamless flow and ordering of universal human organisation" (Campbell, 2011, p. 1456). Campbell (2011) refers to this as "geodisability knowledge," a project that attempts to codify, systematize, and regulate disability under a Euro-Western/colonial standard. This is in keeping with the fact that the production of disability knowledge, social policy and norm setting, and legal reform is dominated by Eurocentrism (pp. 1456-1457).

Chronic pain and fatigue syndromes inhabit a tricky third space that is under-theorized by Euro-Western norm-setting agencies like the CDC or WHO, thus alienating people from the (very real and remaining) issues of Indigenous culture while denoting who is legally disabled, who merits treatment and assistance (Campbell, 2011, p. 1457). Evaluated under these norms, stigmas around karma, marriageability, income, and vicarious trauma become irrelevant, though they are additionally disabling; a condition cannot be legible as paavam, though it can still be cunningly exploited as such. Evaluated under these norms, I am often not "disabled enough" to need accommodations or assistance at my workplaces, conferences, or even continued physical therapy.

There have been times when mutual aid is the only reason I survived.

Scientific orthodoxy insists that we can't infer motivation from archaeological findings, but it appears as though ancient life required coalitional care, an ability and willingness to sustain and enable access for the chronically ill. M9, an adult Neolithic man excavated in Northern Vietnam and dated to 4,000 years ago, "represents one of the earliest known demonstrable instances of survival with a disability so severe as to be inconsistent with life without the long-term intervention of a dedicated caregiver(s)" (Oxenham et al., 2009, p. 107). Vedic and Sangam stories may have served to soften public attitudes towards disability (Narayan, 2004; Mangalam, 2020), but their inconsistent representations ambivalently conceptualize disability. Ravana, like Achilles, embodies anomaly, is unparalleled in the arts of war, is killed by an arrow to an unusually weak spot. Ravana is adopted as an enduring Tamil-Hindu signifier of bodily difference, indigeneity, sovereignty, and war-related tragedy.

All of my myths have at their heart a sage who renounces everything, including mobility and sensory function, and sits still for so long that the elements consume them — like Valmiki, rechristened with that name when he emerges from an anthill (valmika) — and this strangeness, and their easily angered nature, are infra-ordinary. The story of Ashtavakra offers more than the promise that devastating intellect can compensate for physical deformity. Unlike Manthara or Dhritarashtra, he is not a passive character (Kumari, 2019). He does what I think many disabled people sometimes wish they could do: when the Gandharva Kabandha laughed at his appearance, he cursed him. Though disabled, like all sages, the man had teeth.

These ancient literary and historical accounts let us perceive ourselves along a fluid spectrum of somatic difference, from Hephaestus and Achilles to Ashtavakra, Karna, Ravana. In the end, in a far cry from the story of Kubera, I am forced into the cages the CDC has set for me, an afterthought in an inaccessible world that makes even the act of seeking treatment punitive, that suffocates me with the logic of cure every time I ask to be enabled.

(– 132. Such is Maya!)1 Trickster myth tells us that attempts to eliminate contingency, like Freya overlooking the mistletoe in her efforts to protect Baldr, are guaranteed to backfire. ↩

2 Many Hindu deities, from Pillaiyar to Kali, possess multiple arms to symbolize their divine supremacy, but such somatic arrangements are not a mortal commonplace. ↩

3 Disability in ancient Greece was prefigured on aesthetics, ideal beauty being synonymous with symmetry and shapeliness; thus, Hephaestus is ugly, but Achilles is beautiful. This starkly contrasts with Vedic stories, where an asymmetrical form is not consistently treated as "ugly" or "disabled": Kubera is ugly and disabled but respectfully accommodated, but rishi Ashtavakra is mocked. ↩

4 My maternal uncle, congenitally deaf and with upper limb impairment from a bus accident, was not constructed as paavam; despite his visible deformity, his social existence was unremarkable. Years after I met him, grappling with my disability, I reflected on how comfortable he was in his. Just me, he'd signed when I asked about his identity. ↩