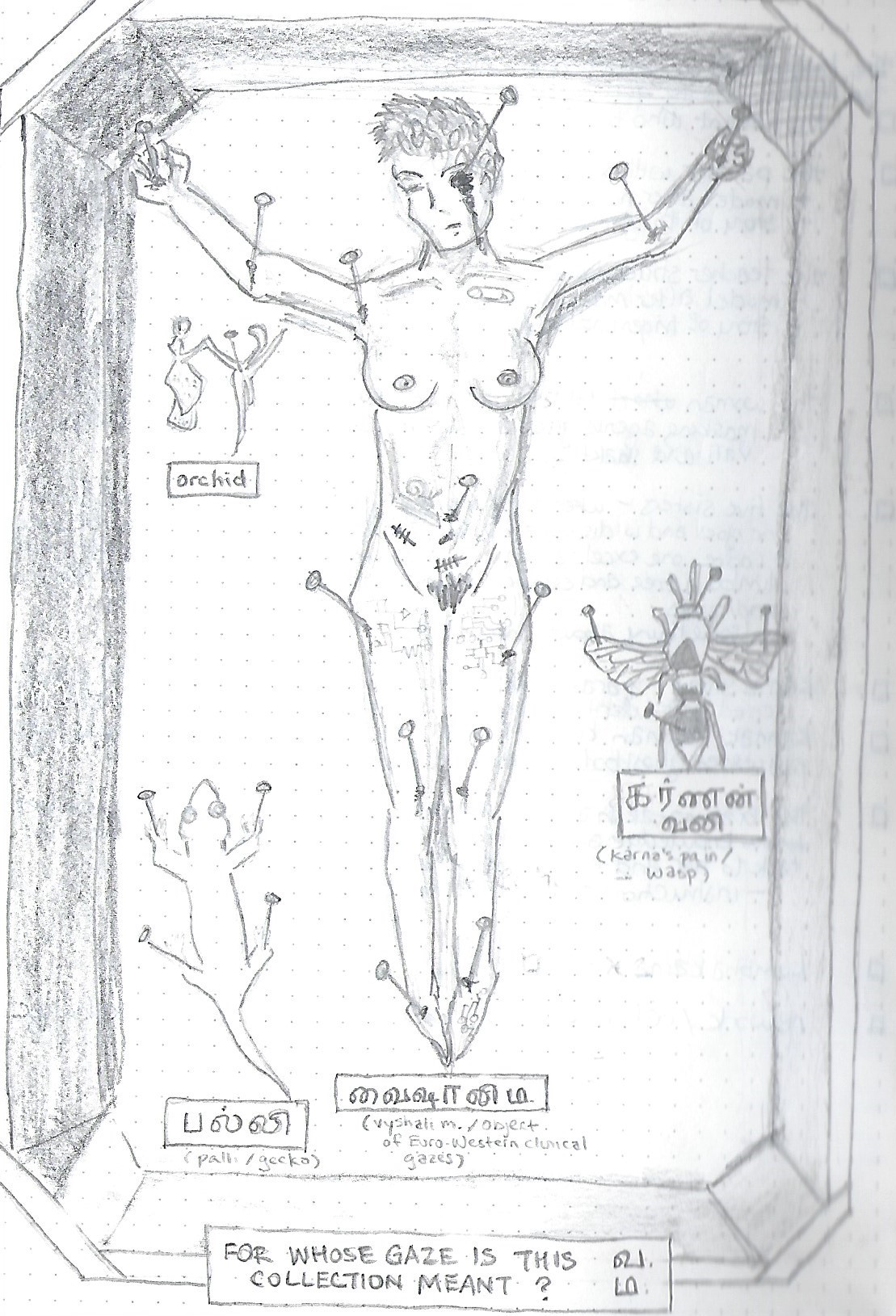

43. For Whose Gaze Is This Collection Meant?

Disembodied as it is, the contemporary medical gaze visually isolates systems and sites of interest inside the body through biomedical technologies that build on photographic technologies, like x-rays, ultrasounds, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography. Technical rendering procedures reify the hegemony of vision by yoking the traditional multisensory clinical approach to visual thinking — the notion that vision is the superior sense because it actively filters data, identifying what is important and culling what isn't, and because it's required to confirm the sensory reality of non-visual modalities (Arnheim, 1969, p. 40). The medical gaze thus reorients towards the virtual projection of the invisible. In Euro-Western biomedicine, the auxiliary senses remained legitimate methods of inquiry only because they anticipated the visible qualities of the postmortem autopsy (Foucault, 1963/1994, p. 165). The eyes predominate even when the other senses are assailed.

Illustrated anatomical atlases were subject to the conventions of visual art and couldn't outpace the body in flux, whereas imaging technologies, particularly those that capture movement, could. Anatomical illustration and medical portraiture objectified and catalogued visibly deformed or diseased patients but couldn't penetrate the opaque body; they "enfreaked" and abjectified disabled subjects through a didactic visual language that was influenced by social attitudes and cultural stigmas (Barnett, 2014; Siebers, 2010). Purportedly omnispective and impartial, the biomedical camera depersonalizes and transparentizes the opaque body through computerized, comparable images that serve as visual standards of visceral normalcy and health. The image rendered through mechanical eyes is considered infallible, as the photograph is supposed to capture without bias and is presumed objective, authentic, and evidential (Tagg, 1988; Crary, 1996).

Any optical apparatus, however, is what Deleuze and Guattari (1980/1987) would describe as "simultaneously and inseparably a machinic assemblage and an assemblage of enunciation" (p. 507), the convergence of material practices and a discursive formation. Biomedical authority is predicated on the use of technological instruments to make disorders visible and reduce reliance on patient narrative, but like anatomical illustration, imaging scans are collaboratively generated through a human-machine assemblage. The machine is social as well as technical and material (Foucault, 1963/1994; Deleuze & Guattari, 1980/1987).

The camera decisively reorganized the relationship between representation and the observer. Vision is decorporealized: the machine operator withdraws from the world — behind the photographer's black curtain, into a state of interiority, or into an adjacent radiology control room — and reenters it through the mediating mechanical apparatus, as a disembodied witness whose physical, sensory experience has been supplanted (Crary, 1996, pp. 39-41).

The eye is stubbornly physical. Philosophers like Locke, Condillac, Foucault, Kant, Goethe, and Schopenhauer variously understood vision as perceptible knowledge in the classical era, as an object of knowledge itself, as a biological process originating in sensory organs and anatomical structures, as subjective (pp. 69-94). Visual perception is made possible by fallible physiological features and structural limitations: like the muscular movements of the eye and eyelids; or the punctum caecum, the obscuration of the part of the visual field that corresponds to the absence of photoreceptors on the optic disk where it intersects with the optic nerve. The eye has difficulty perceiving objects that are too close or too far away. It is susceptible to visual illusions, and requires compensating senses (like touch) to confirm what is there (Jay, 1993, p. 8).

By contrast, machinic vision presented itself as trustworthy, disciplined, and reliable. By the 19th century, coinciding with the development of commercial daguerreotype and calotype cameras, the eye had become the site of power and truth, as subjective observation was grounded in its anatomical functioning (Crary, 1996, p. 95). Knowledge of the body and its operational modes made the subject compatible with new arrangements of power, such as the prison, the asylum, and the clinic (Foucault, 1966/1994, pp. 349-351). Vision was re-corporealized: that is, the body of the observer is isolated from the technical apparatus but tenaciously abides in the image. The "pure" objectivity promised by an optically neutral instrument is marred by the subjectivity of the observer who selects, frames, and gazes based on prior experience and optical anatomy.

Photography's success in the medical field depends on the denial of bodies, both patient's and observer's, despite the embodied nature of portraits, biomedical imaging, and the physiological processes of vision innate to observation. Photographic objectivity depends on the denial of the human-machine assemblage responsible for the picture and its interpretation. But the medical image depends on a team: I describe my painervation to a physician, who chooses the imaging modality and location to be photographed and sends me to a radiographer, who engages in photographic acts of selection before submitting the images to a radiologist, who interprets them and provides an opinion, which the physician uses to bolster or disprove a potential diagnosis.

As Sontag (1973) says, "Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe" (p. 1), reshaping subjective notions as objective, foregrounding denotations and mystifying connotations, confirming a representation of reality as though it is the only one. And yet, "what does one see when one's eyes, depending on sighting instruments, are reduced to a state of rigid and practically invariable structural immobility? One can only see instantaneous sections seized by the Cyclops eye of the lens. Vision, once substantial, becomes accidental" (Virilio, 1994, p. 13). The lens standardizes our ways of seeing and reduces the human visual field and its sensory interactions to a solely optical apparatus, altering the ordering of vision even as it expands the reach of the eye into the body's interior.

Photography and the Ordering of Vision

The promise of early photography, underscored by the industrialization of camera technology, was expansive capture, a project that paralleled the aims of the biopolitical state. The power to bestow authority on photographs comes from all the conditions of its production, circulation, and consumption within a particular social context, including accompanying text, interpretive standards, and so on. Mitchell (1994) characterizes the encounter between the image and the eye as a manipulable space that is invaluable to power, as disciplining visual perception and representation is crucial to the technology of sovereignty (p. 61). According to Tagg (1988), the status of photography as a technology "varies with the power relations that invest it. Its nature as a practice depends on the institutions and agents which define it and set it to work. Its function as a mode of cultural production is tied to definite conditions of existence, and its products are meaningful and legible only within the particular currencies they have" (p. 63). It must be studied as a field of social and biopolitical operations, not simply a medium.

In scientific fields, mechanized observers could replace fatigable, distractible human observers, expressing the triumph of reliability and self-discipline over the foibles of the flesh (Daston & Galison, 1992, p. 83). Although spirit photographs have cast suspicion on the neutrality of the photographic image, it retained an aura of objectivity, giving equal emphasis to everything in its frame whereas artists could foreground or deemphasize parts of a scene or dissection (Tagg, 1988; Daston & Galison, 1992; Baer, 2005). Photographs could furnish incontrovertible evidence of a moment in time. Within three decades of its invention, the technology was used for

police filing, military reconnaissance, pornography, encyclopedic documentation, family albums, postcards, anthropological records (often, as with the indigenous peoples in the United States, accompanied by genocide), sentimental moralizing, inquisitive probing (the wrongly named "candid camera"), aesthetic effects, news reporting and formal portraiture. (Tagg, 1988, p. 52)

Photography has since come to shape our relation to memory and embodiment. Dolphin-Krute (2017) likens imaging scans to medical-social portrait photography given their technical similarities (p. 35). The camera popularized portrait photography, an art form that emerged from the tradition of bourgeoisie oil paintings that ceremonially presented the self and thus symbolized social status. It was concurrently adopted in legal and medical protocols to establish a hierarchy of Othering archetypes — heroes versus criminals, the wealthy versus the impoverished, the intelligentsia versus the insane — but always represented the body, albeit in standardized poses, as belonging to an individual (Lury, 1997, pp. 43-45). Unlike candid photography, the portrait photograph is never accidental: it must be arranged, staged, consented to. As Barthes (1980/1981) says: "Once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of 'posing,' I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image. This transformation is an active one: I feel that the Photograph creates my body or mortifies it, according to its caprice" (pp. 10-11).

The photographer, self-aware at the moment of taking the picture, inscribes his subjectivity in the resulting portrait, in his choice of formal arrangement and moment to capture. The photographed, objectified subject signifies the "thereness" of reality while also comprising the connotations associated with it and the social meanings attached to the formal and technical conventions of photography — such as lighting, camera angle, perspective, and so on — used to organize the image (Barthes, 1980/1981; Sontag, 1973).

Photographic aesthetic principles came to be cross-cut with judicial, medical, and epistemological conventions and concerns (Tagg, 1988; Dumit, 2004). The legal and medical fields strove for an aesthetically "neutral" standard of representation (Lury, 1997, p. 52). In scientific disciplines, procedural and mechanical safeguards against subjective and aesthetic bias were installed around photographic depictions like x-rays, lithographs, camera obscura drawings, and ground glass tracings (Daston & Galison, 1992, p. 98). The photograph became a key technology of power-knowledge since the 1870s in the clinic and other institutions that used documentary images to order the conduct of social life. Medical photographs of living patients enacted the intimate observation and subtle control of Foucault's disciplinary power and continued to substitute for the patient's voice. Physiognomic representations of asylum and clinic inmates were meant to procure visible indicators of interior derangement, linking external manifestations to internal disorders like insanity and syphilis (Tagg, 1988, p. 78).

This paves the way for the opposite to become true, for internal disorders to exist only if an external manifestation can be imaged.

Doubly authoritative as photographs and artifacts of medical pedagogy, medical photographs establish the authenticity of illnesses, as with Charcot's Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, a three-volume compendium of photographs of women in the throes of hysteria. In his documentation of hysteria, Charcot recognized that photographs reveal more than the photographer might have perceived or intended, so he studied his case records for "spectral residue" (Baer, 2005, p. 14) — ghostbodies. "When the camera's objective (its lens) is positioned between doctor and patient, the photographic set-up offers the illusion of objectivity — the empirical existence of an objective distance between observer and observed that the medical establishment had long sought" (Baer, 2005, p. 33). The medical photograph follows certain aesthetic conventions, such as the framing of full body profiles, varied postures, close-ups, and serial shots of one subject, but it is determined not to be seen as an aesthetic genre; rather, the aesthetics foist upon the observer a sense of empirical objectivity (Siebers, 2010, p. 45). Pathological manifestations are fluid and mobile, and medical portraits record a lasting trace of the symptom, permitting a clinically distant study of the subject. The images in Iconographie provide visual evidence of baffling somatic disturbance and link cryptic pathological presentation to objective technologically visualized proof.

Hysteria, etymologically derived from the Greek word hystera, or uterus, does not feature in ancient Greek medicine. Its earliest analog is the "wandering womb" codified in Hippocratic and Galenic treatises. Hysteria persisted in Euro-Western medical and religious thought for centuries, a wastebasket diagnosis for the condition of being a woman, until it fell into decline in the 20th century. Didi-Huberman (2008) suggests that hysteria was a pain that clamored for invention, that Charcot's method of concretizing its symptoms in photography fabricated the condition as a "spectacle of pain": the pain of physical and mental illness, of medical experimentation, of the civic death by disenfranchisement caused by illness, confinement, fetishization, poverty. The woman sufferer, provoked into symptom manifestation, evinced a cataleptic body articulated at will, a hyperesthetic body riddled with pains or anesthesias, the inability to feel, and hyperalgias: arthralgia, myosalgia, dermalgia, cephalgia, epigastralgia, pleuralgia, thoracalgia (Didi-Huberman, 2008, pp. 193-195; Morris, 1991, pp. 118-124). "Every organ of the hysterical body had its own pain" (Didi-Huberman, 2008, p. 177).

"Hysteria, both ancient and modern, provides important evidence that pain is constructed as much by social conditions as by the structure of the nervous system" (Morris, 1991, p. 104).

Hysteria is a point in fibromyalgia's timeline. It's predominantly feminine, prone to histrionics, deception, imitation, masking. A catchall diagnosis. By photomechanically catching the hysteric in the act, Charcot hoped her manipulations would unravel. "To diagnose a disease that introduced what Jean-François Lyotard has called a differend between female patient and male doctor (as two parties who lacked a common idiom), Charcot used photography to visually represent a disease that defied anatomy and, thus, physical examination" (Baer, 2005, p. 30). These portraits of hysteria, intended to provide unfiltered access to its symptoms, ended up fabricating a taxonomy of symptoms that "count" (Didi-Huberman, 2008, p. 4). Hysteria is no longer a recognized illness, but its traces persist in modern disorders, from anxiety and schizophrenia to fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Photography permitted the mass production of images for indexes and anatomical texts, facilitating the enterprise of collective empiricism and linking the disciplinary medical gaze to particular representations of the dissected body. The pedagogical use of medical photographs ensured a shared community of principle and practice that standardized methods of observing, comprehending, and treating the diseased body (Barnett, 2014, pp. 20-34; Daston and Galison, 1992). But the portrait of pain remains haunted and two-faced: simultaneously individualizing, emphasizing the subject's inner self, and threatening individuation, absorbing the individual into a standardized taxonomy of humanity, femininity, chronicity, and pain (Lury, 1997, p. 47).

Photographs of fibromyalgia, concretizing nothing, cannot be nosological. But the photograph promises to exteriorize invisible symptoms, render disorders visible and graspable, and advance medical mastery over the body; and the photographer is positioned as the impresario of the patient's chronic pain. There is a reason they call it a medical theater.

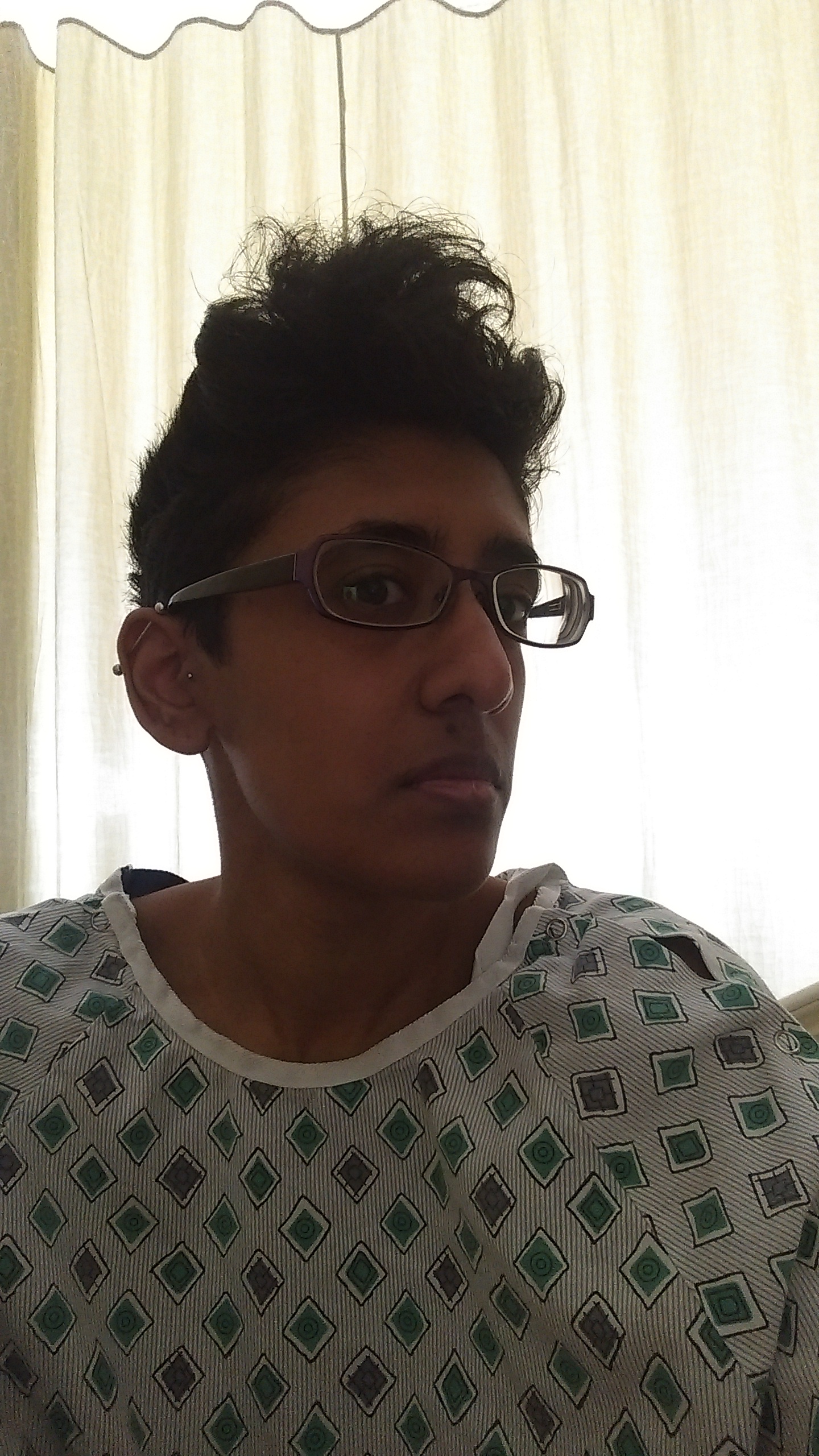

In the only selfie I take in the ER in 2014, I am not visibly unwell. I look gaunt to myself. My eyes are tired but alert and focused. My mouth is set in a grimace that might be pain, might be frustration. I look like the product of an academic career, except for the incontrovertible signifiers of illness in the image: the hospital gown, the curtain drawn around the bed, sunlight behind me darkening my skin. My hair is frizzy from agitated half-sleeps. Apart from two earrings and a nose ring I never remove, I am not wearing jewelry, though I was raised to never leave the house without it lest I look poor.

It's a portrait of my own anger, taken to share on Google Chat with Anji, Mary, and Sara, but as with all photographs, "to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude" (Sontag, 2003, p. 46). Included: my eyes, aimed sidelong at the camera, an enigmatic overture or appeal; the dark hollows under them, slightly covered by my glasses; the crease at the center of my chapped lips, which is also at the center of the image; my industrial bar and tragus piercings; my faux hawk with its flyaways; the gray pinstripe hospital gown patterned with green diamonds, one of the back ties pulled to the front, a hole in the shoulder; the flimsy hospital curtain behind me, filtering the morning sun. Excluded: my gold diamond nose ring; my tattoos; my other piercings; the IV line, the IV stand, the bruise blooming around the peripherally inserted central catheter, the bright yellow medical bracelet labeling me a fall risk. All the signifiers of Tamilness and sickness and stoicism, absent.

If it weren't for the hospital gown, I doubt I would even be hailed as ill. But every photograph I take of myself to document a symptom, a manifestation, a ghostly trace of chronic painervation, is a portrait of disability.

In Baer's (2005) words, "there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed" (p. 10). Even and especially when the subject has no choice but to consent if they want to survive.

Seeing Fibromyalgia

The importance of vision in evidence-based medicine dates to premodern times: Kuriyama (1999) describes the attention Chinese physicians paid to color as part of their "faith in visual knowledge" (p. 153): "Wang er zhi zhi — to gaze and know things, the pinnacle of medical acumen — was thus to know things before they had taken form, to grasp 'what is there and yet not there'" (p. 179). Ayurvedic physicians are trained to rely on sight, touch, and hearing, though Ayurvedic practice deemphasizes the importance of ascertaining the name of the illness and presents diagnosis as mutable and always-becoming in a continuous process of examination and treatment (Brooks, 2018). In Whelan's (2009) study of pain scale standardization, she argues that, since vision is a selective sense, what it privileges about the pained body is how that body becomes classified and ordered as a result of technical interventions in an attempt to "make pains the same" (p. 171). Accordingly, popular classification systems privilege the location of pain and visual assessment of the patient's reaction to being palpated there over other cues such as vocalization or smell. Additionally, the proprietorial gaze of radiological interpreters prevents patients from fully accessing intimate information about their bodies, exacerbating the experience of dispossession and radical self-estrangement.

Fibromyalgia, with its personalized fascia arrangements, inherently resists standardization through trigger point arrangements, imaging exams, and ocularcentric thinking. Effective treatment depends on the physician's willingness to assess in more ways than one. The fibromyalgic self is transformed by the interventions of biomedical technology, which allege irrefutable proof (or lack thereof) of pain through diagnostic imaging. Forms of diagnostic imaging promise to construct a picture of pain that is irrefutable, in contrast to assertions that to experience of pain is to experience the certainty that you're in pain while onlookers are left in doubt (Dumit, 2004; Scarry, 1985). It's a practice of subjectification rooted in the imaging procedure, which somaticizes individuality and reduces personhood to an investigative technique (Rose, 2007).

Perhaps it is worth noting that Ayurvedic practitioners question the impact of diagnostic technologies on physicians' sensory diagnostic capacities, that physicians' aspiration to the idealized sensory state described in the Suśruta Saṃhitā and Caraka Saṃhitā encourages a reliance on the kind of intuition born of embodied clinical experience (Brooks, 2018, p. 107). Or that Ayurvedic and Siddha medicine construct diagnosis not as a singular event, but as a constant, multisensory, non-linear unfolding (Brooks, 2018; Wujastyk, 2008).

If the myth of total transparency presumes that seeing is curing, then a pathology that isn't visualizable defies treatment, the clinic, and biopolitical control (van Dijck, 2005; Foucault, 1963/1994).

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic imaging gives us new tools and procedures for the management of the body, changing the foundations of knowledge production, distribution, and application, a response to the spreading notion in the 1800s that "anatomists and physicians could no longer rely on fallible human artists to represent their discoveries. Scientific and medical image-making should, like so much else in the 19th century, be isolated from the bias and imprecision of human craft through automation" (Barnett, 2014, p. 34). The imaging scan substitutes for patient experience, as the patient in "real" pain is believed arhetorical given the incommunicable dimensions of suffering. Diagnostic imaging amplifies ocularity to commute the mysterious inner workings of the body into incontestable matters of fact; they are imbued with the power to legitimate disorders like fibromyalgia that are imperceptible or confusing to the senses (Shapin & Schaffer, 1985).

Virilio (1994) suggests that with the development of computerized photography, the collapse of vision to the camera's line of sight contributed to the subordination of the minor senses to sight and to the automation of vision and the narrowing of mnesic choices. The photograph implies a correspondence between the photographer's perspective and incontestable objectivity. In the words of Dolphin-Krute (2017), "Interpretation is a temporally grounded and ongoing process and as such, it is distinctly open. As inseparable from their interpretation and as interpretation is not static, medical images are an ongoing process and product" (p. 35).

Perhaps medical imaging technologies — with their photographic techniques, pretense of objectivity, and subjective interpreters — also engage in the work of enfreakment. My internal strangeness, belied by an ordinary exterior, is presented as fact and spectacle to radiographers and radiologists who gasp, "Your pelvis looks like a bomb went off," or "What is that? What is that?"

As in portrait photography and medical portraiture, imaging scans stage the subject's pose and select particular moments in time when the picture is taken (Barthes, 1980/1981). As a technology of moments, photography captures the acute event or traces of chronicity so banal to the subject that they are scarcely noticeable. "Chronic illness is like a perpetual leaving of disease, a constant cycle of recording, partial erasure, and reinscription" (Dolphin-Krute, 2017, p. 11), such that chronic itself might be a symptom of the failure of photography to render chronic pain visible. The depersonalized snapshots of a patient's interior "call on the patient to align herself with their reality, demanding to be read as factual evidence of a match between the inside of the body as 'specimen' and the inside of the body as the private and incontrovertible ground of experience" (Rhodes et al., 1999, p. 1193).

To my detriment, I never match. In the ER, it wasn't until I did that I was taken seriously.

Imaging technology changed the nature of the body-as-spectacle. Anatomical atlases and medical photographs associate the visual with factual documentation but can't depict the body's dynamic processes or rid themselves of contemporary aesthetic codes (Siebers, 2010; Daston & Galison, 1992; Barnett, 2014). Empirical science already sought to displace artists by converting to an automated means of representation, a photomechanical process that eliminated handworkers from the production cycle and artistic interpretation from anatomical atlases (Daston & Galison, 1992, p. 100). The advent and application of medical imaging technologies likewise policed subjectivity and preserved a veneer of respectability by creating a solidified distance between physician and patient, separating the patient in her state of shameful transparency from the physician's spectatorial appraisal of the most private of bodily depths (Howell, 1995). With advances in imaging technologies, the camera eye acquired the capacity to broach the body's boundaries before postmortem autopsy, permitting views without dissection and weakening connotations of violence and prurience around medical imaging (van Dijck, 2005, p. 11).

Prolonged mechanical observation via the intersection of human and technological gazes and patient discourse aligns with a pattern of study in which disease, especially commonplace events like a headache or a ruptured appendix, is repetitive and recognizable in its repetition (Foucault, 1963/1994, p. 110). By the turn of the 20th century, photomechanical renditions of pathology were meant to evoke a class of patterns in viewers' minds, transferring fears of subjectivity from the image itself to the audience judging it: in short, machine operators could claim that bias, artistic or otherwise, was imposed not by the technology, but by diagnosticians (Daston & Galison, 1992, p. 107).

Healthcare is a complex of commercial practices that support the project of quantification for massification. To this end, the fetish of the visual in biomedicine is stubbornly persistent, even regarding imaging techniques that yield inconsistent results or are otherwise questionable: for instance, the injection of contrast material into the joints or bloodstream, the digestive use of nuclear medicine to measure gastric emptying, or the metrics offered by wearable technologies that claim to monitor physical fitness or mental acuity — all of which reduce experience to a biochemical model (Mol, 2002; Baszanger, 1998).

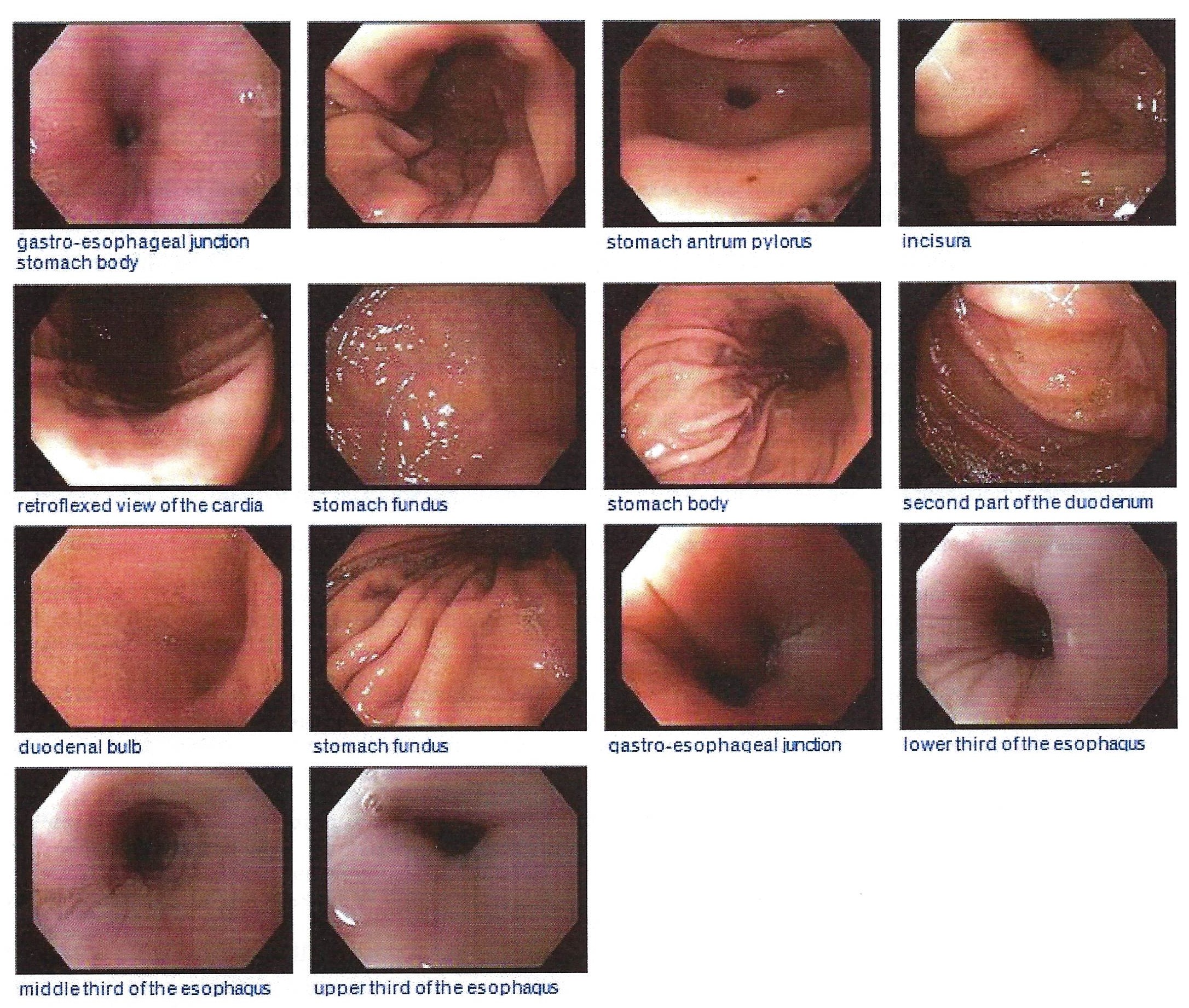

By the 20th century, "selection and distillation," the most subjective of machine operators' choices, "previously among the atlas writer's principle tasks, now were removed from the authorial domain and laid squarely in that of the audience" (Daston & Galison, 1992, p. 110). This attitude ensured that individual mechanical representations retained their objective purity. After a 2021 endoscopy, I am told that my upper GI tract looks good, though the official written diagnosis is chronic gastritis; I am told that there is malrotation, recorded with a ? on the radiological report; I am told that there is evidence of a recent small bleed, already healed and scarred over. I am not told which picture it is, but my guess is the stomach antrum pylorus, the only photograph where the glossy, slippery tissue is marred by a small dark dot. I have elsewhere mythologized the pylorus as the portal to the afterlife, and I feel artistic vindication at this, but I am also proving that the interpretive bias lies with me, the viewer, imposing fantasy onto a neutral, empirical picture.

The routinized, automatic operation of the endoscope camera or non-invasive imaging scan is made to seem unprejudiced and authoritative, but machine operators are human, and the image is vulnerable to human choice: where they place the camera, how they position the patient, whether or not contrast media is used, the number of pictures taken, which pictures are designated key images. Medical imaging shows only what exists and nothing else. No ornate backgrounds. No astrological figures. No painterly artistry. The microscope, the photograph, the diagnostic image, they all persuasively converge in the dream of perfect transparency.

But as van Dijck (2005) reminds us, the claims of increased transparency that accompany each new imaging technology are exaggerated or false. Each new application — x-rays, ultrasounds, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography — reveals new physiological layers seen only through the specific modality of the new visualizing instrument. Combining all these perspectives, assembling all my pictures here, does not and cannot produce a whole, wholly transparent body. Digital imaging is a form of monogeneric capture if we don't consider the social and cultural systems in which vision is embedded and if we don't consult other modes of perception.

So for whose gaze is this collection of images meant? The radiologists who issue and interpret them? The physicians who receive, explain, and archive them? The academics who will peruse them like ghost stories and decide if the subject qualifies for a doctorate, awards, promotions? The community of chronically ill patients for whom radiological and pathological interpretation is necessarily a clumsy second language? The friends and family members who will understand them as signifiers of trauma and debility? Me?

(Not me. Never me.)

If fibromyalgia is a disorder symptomatic of the contemporary era as Morris (2000) has claimed, the need to visibilize it in order to eradicate it is imperative for the state and imperils the fibromyalgic subject, who requires a long-term managed care approach and not high doses of analgesics or antidepressants. This effort begins with visual assessment, as the biomedical conceit that human and machinic vision can verify the authenticity, intensity, and location of pain. If inflammation or injury can't be technologically rendered, it's like the disorder doesn't exist.

Perhaps "the way to witness a figure whose wholly visible form may only ever be partial is not to picture it, to form a representation of it, at all, but to let the figure appear" (Dolphin-Krute, 2017, p. 2).

(–97. The Voice That Betrays)