49. The Body Acoustic

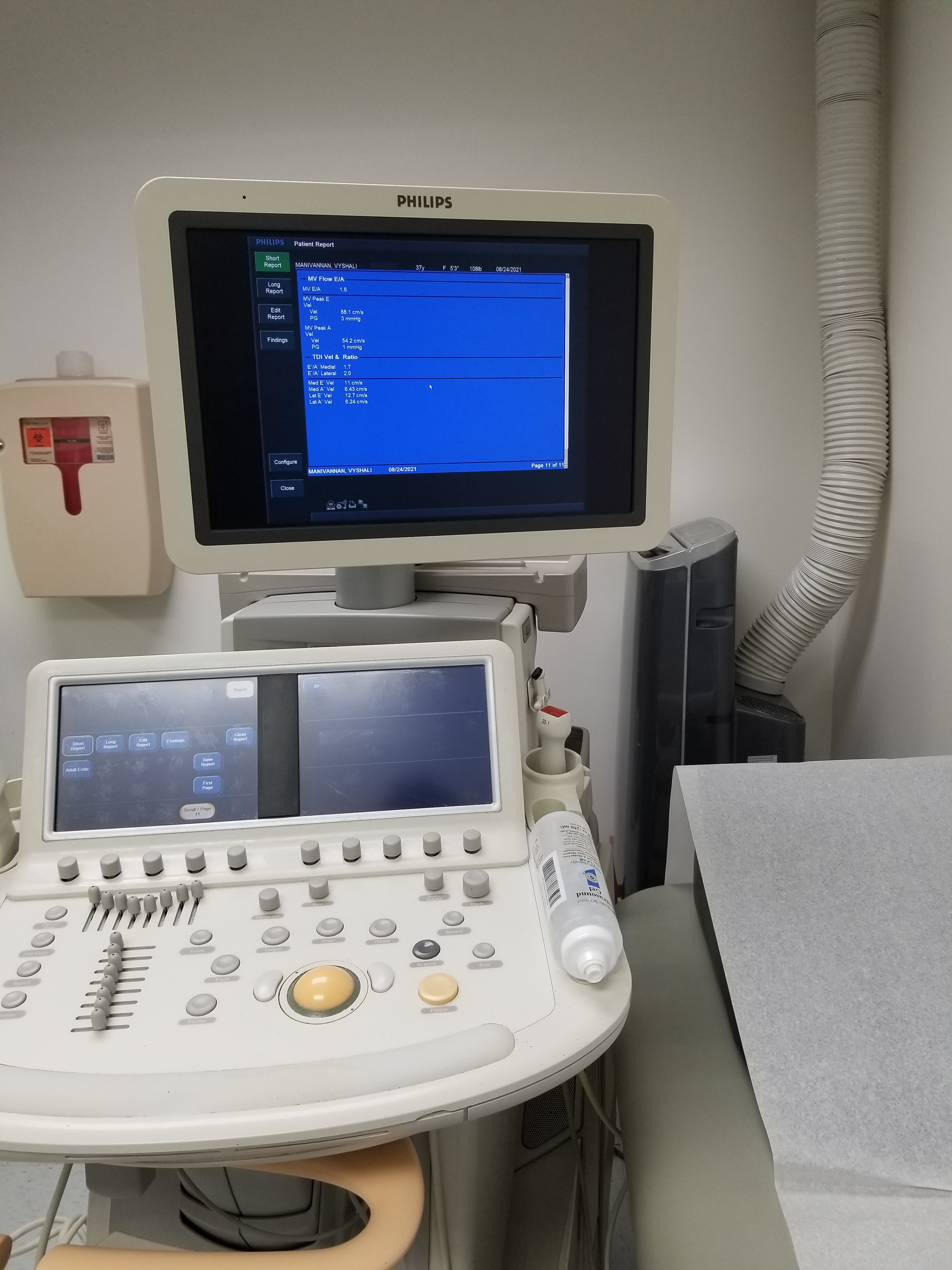

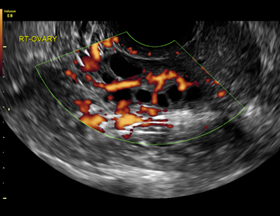

Ultrasonography (US) is a form of diagnostic medical imaging that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce dynamic pictures of anatomical structures and processes. The skin is coated in a conductive medium that creates a bond between the flesh and the ultrasound transducer, a device that transmits and receives sound. It sends high-frequency sound waves into the body and detects how they reflect off organs and tissues (as different internal structures differently reflect sound) and converts these impulses moving pictures and still photographs of the organ being imaged. This imaging modality contains three layers of technology and visibility: the ultrasound, or the procedure itself; the ultrasound image, the real-time visualization produced on a monitor by the conversion of sound waves to data; and sonograms, or select still frames of the ultrasound image captured during the ultrasound procedure (Frost & Haas, 2017, p. 93). Ultrasonography is a routine procedure in women's health, more so than the ubiquitous x-ray. Pelvic pain, irregular menses, and heavy menses warrant a visual inspection for ovarian cysts, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), uterine fibroids, fallopian tube blockages, torsion, inflammation, and other problems endemic to the female body. The technology is also used to monitor (and is more commonly associated with) pregnancy and fetal health.

Ultrasonography is used for other diagnostic purposes as well, such as assessing blood flow or evaluating the structure of the gallbladder, liver, kidneys, or heart. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) procedures, for instance, evaluate the structure of my heart, its pumping action, and the motion of blood through its chambers. As it is popularly associated with female reproductive health and maternity, however, the word ultrasound has come to connote pregnancy, motherhood, and the visible fruitful womb (van Dijck, 2005). The word evokes gynecological procedures and fetal images more immediately than it does pictures of the heart or veins. For women, the full pelvic ultrasound, which I have undergone twice since my appendectomy, consists of a transabdominal ultrasound, where the stomach is coated in conductive gel and the transducer is rolled back and forth across it, and a transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), where a transducer that resembles a dildo is vaginally inserted to visualize organs in the pelvic cavity by sending waves across the vaginal wall.

The kinder radiologists cheerily warn me, "You'll just feel a little pressure," and are completely unprepared for my staccato cries, my ragged breathing, how I grip the exam table paper until it tears when they push the probe in. All behaviors I developed after Dr. Tamas examined me in September 2014.

Being kinder, they apologize profusely. I forgive them. Neither of us signed up for torture. Neither of us can just stop.

This is deemed noninvasive, as it doesn't require incision into the body, but it violently penetrates the body's folds; it's a dubiously consensual fucking by the medical eye.

Transvaginal sonography has been in widespread obstetrical use since the 1980s, allowing physicians to see the female interior without having to directly view or touch the patient's vagina (Kukla, 2005, p. 117). In the 19th century in the U.S., the speculum — the first medical instrument of colonization and control of the female body — was considered unjustifiably indecent except in emergencies. Howell (1995) explains that "the moral issue was not physical but, rather, visual contact: there was no problem with a male physician examining the female genitalia, even breaking down the hymen with a finger, so long as he did not look" (p. 147). The gaze was a far more potent cultural symbol of eroticism, a far more potent transmitter and receiver of evil, that unlike touch was deemed difficult to control and locate. As a result, male physicians in charge of caring for respectable women had to operate by touch, without the gaze, and look only in an emergency (p. 147).

In other words, it's better for "respectable women" to suffer extreme agony than to "waive decency" (Howell, 1995, p. 147). This thinking aligns with the middle-class aversion to prurient spectacles of pain, which arose during the 19th century as well (Halttunen, 1995).

I have done this many times. A few times in the early 2000s, to diagnose pelvic pain, exclude endometriosis and PCOS, and evaluate my heavy menses and dysmenorrhea. In 2012, to detect and measure ovarian cysts. That little pressure, an awful but doable obligation. After the appendectomy, in 2015 and 2021, I exit myself and hover by the ceiling while the probe sends aftershocks up to my navel. Whoever the radiologist, whatever they say, I have to fight to hear something other than Dr. Tamas' voice.In the late 19th century, the x-ray still occupied this medical and social position, used to diagnose sensitive issues like pregnancy by visualizing a fetal skeleton. Imaging procedures were thought to protect a woman's privacy and her reputation, as male physicians could examine her from a safe remove without viewing her genitalia as incorrect verdicts about her pregnancy or fertility could tarnish her respectability (Howell, 1995, pp. 148-150). Unlike the x-ray machine, the ultrasound transducer for transvaginal sonography has a sexual shape and heft and still requires manual vaginal insertion by the physician, which requires the physician's initial gaze. Covered with a condom and lubricated prior to this penetrative act, the transducer is essentially an ultrasonic dildo, one that — after a quick peek for guidance — allows physicians to train their eyes on computer screens, a shield against the affective contagion of the patient's grimacing face and fleshy winces. Both her pain and her intimate parts can be visually avoided without sacrificing the view of the body.

Like other medical images, the sonogram is an artifact I am legally entitled to, but it is also a site of embattled expertise.

By September 18, 2014, I have been in the ER for an afternoon and a night over a chronically perforated, ruptured appendix that is being diagnosed as anything but. I silently underwent the diagnostic CT scan Dr. Jiang ordered before going to the ER. There, the white man physician's assistant who admits me, Mitch, half-listens to me explain that I have fibromyalgia, that I haven't eaten in weeks, that my bowels are hard and rebelling, that death is preferable to the abdominal pain. He suggests pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), often caused by untreated venereal disease or IUD complications. I tell him I'm not sexually active, don't have an IUD, never had penetrative sex with a male partner, never douche, rarely even use a dildo for masturbation. He assures me PID isn't linked to sexual activity, then asks repeatedly if I'm having intercourse, if I'm pregnant, and pulls skeptical faces when I insist no. He orders a transvaginal ultrasound, which I don't think makes sense. He says, "It's the only way to be sure."

I'm wheeled on a gurney to the radiology room by two attendants who refuse to talk to me. The OB/GYN radiologist, Dr. Tamas, a South Asian woman, matter-of-factly introduces herself as she prepares her equipment. I remember to flag that I have a chronic pain syndrome, but I don't think to brace when she pushes the transducer inside, clearly expecting no resistance, and rams it headlong into the hard ball of pain I've been incubating. How tightly I've controlled myself since January, I realize, when I derail into sobs and screams, when I need breath, when my diaphragm won't work and rations my air, when I scream and all that comes out is a thin, reedy noise. Intent on the computer screen, Dr. Tamas ignores my frenzy to escape and wiggles the camera deeper, repeating, "What is that? What is that?," first with the fascination of finding an anomaly, then irritation that she can't give it a name. I cringe up the gurney as the probe interrogates all the tender places I've guarded for eight months, one step away from four-point restraints with the way the older Latina nurse moves to hold me down at Dr. Tamas' sharp, "You need to hold still."

I can't. I can't.

It's an Amma or Chithi I wanted; it's a rakshasi I get. She scolds me for moving. Every new twist of the probe wrings bile into my mouth that I have to swallow back. The nurse smoothes my hands, over and over, speaking gently to me in Spanish. "It hurts," I gasp. I can feel, inside, the alien thing she's bruising with it, and I start screaming, which kills me afresh as my diaphragm bears down to make sound. It's a vicious cycle I can't explain when Dr. Tamas asks, visibly exasperated, "What hurts?"

Everything is not the right answer, and I am not rewarded for it (Foucault, 1963/1994).

In the end, the camera finds nothing, as I predicted. It never does with me. But who am I to protest? An unreliable narrator, already suffering from an unreliable disease. In the end, Dr. Tamas indicates she can't get her clear picture, and I'm wheeled away like a recalcitrant little girl who won't learn her lesson. Fibromyalgia means this pain echoes in me for days. Trauma means it never left.

She spent the entire exam staring at her screens, never once palpated me, or acknowledged my pain and terror, or looked me in the eye.

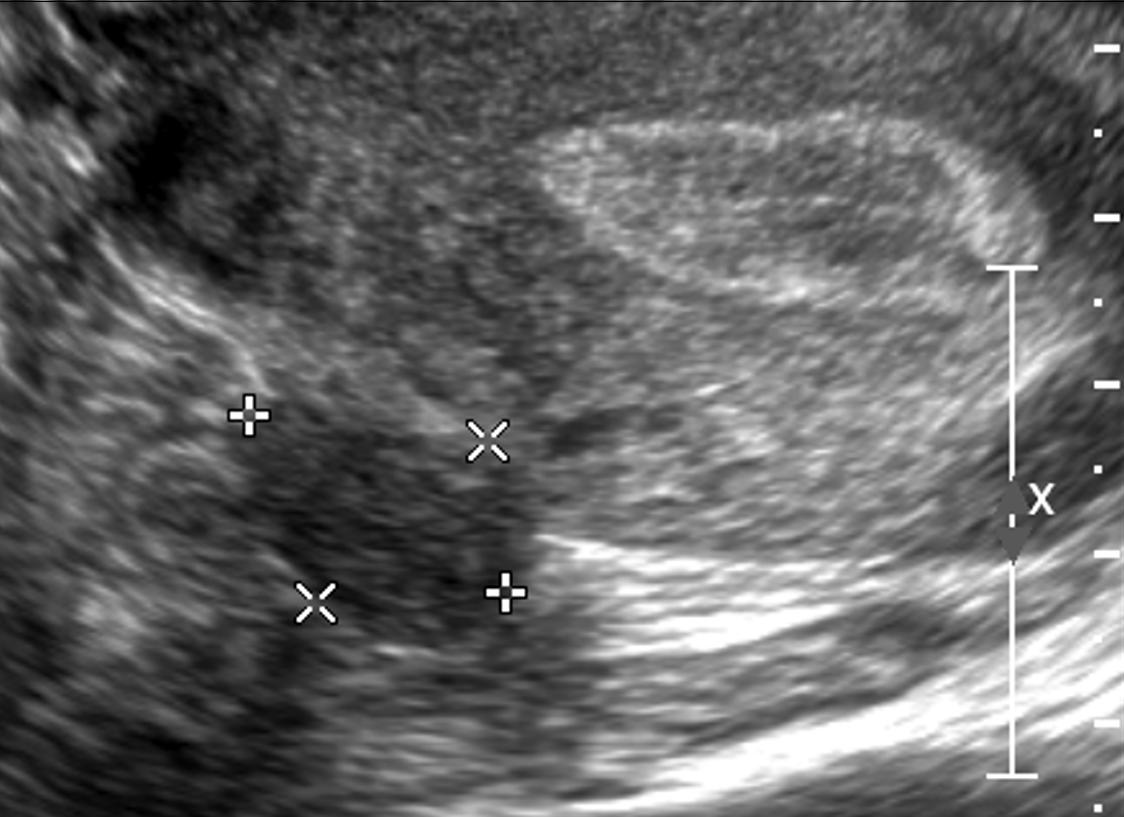

Compared to x-rays and CT scans, with their recognizable bones and organs, ultrasound images are notoriously difficult to parse (Kukla, 2005, p. 114). Most of the sonographic images I possess are of my uterus and pelvic region, and I pore over them in native diagnostic viewers like NilRead on CDs or electronic portals, reminded by the cryptic pictures and the digital interface that — even though I can navigate through them and save them locally, even though they are my body — these pictures are not meant for me.

Anatomical illustrations of fetuses tended to abstract the uterus from the pregnant woman's body, and the visual codes of the TVUS recall this in the grayscale trapezoidal view of the womb without the shape of the body it belongs to (Kukla, 2005, p. 73). As it is hard to decipher an ultrasound, Kukla (2005) reports that many pregnant women, after a routine ultrasound, "adopt the mediating third-person stance of the sonographer as their own for the purposes of understanding their encounter with their fetuses through the ultrasound image" (p. 114). More medically significant than socially significant when it isn't prenatal, the diagnostic ultrasound doesn't always merit a coincident explanation, and the patient is not guaranteed copies of the image. I order CDs, wait for the radiology report to be released to me, and match the findings to the pictures as best I can. Sometimes the radiologist has marked, measured, and labeled the anomalies, as in a 2021 pelvic ultrasound that confirmed the presence of uterine fibroids, the boundaries of a pedunculated fibroid marked by +'s and X's.

Of all my images, I am most illiterate in sonography. I am first struck by the aesthetic properties of the image, not the clinical signs it contains. My carefully curated archives are principally dictated by personal meaning and artistry. It is easy to justify inclusion on the basis of aesthetic criteria when all of the medical photographs in my possession have been deemed insignificant, unremarkable, normal. My ultrasound images from 2014 were never sent to me when I requested copies of my medical records and imaging exams. What I have are still images from my 2017 follow-up, chosen for their visualized contents and photographic composition. You can't tell from any of them that I was still in pain and terrified, gripping the sides of my gown so tightly my hands blanched.

The body is always in flux, so subsequent ultrasounds can't substitute for the unseen images from 2014, at a moment of bodily crisis. I have Dr. Tamas' interpretation, but radiological notes are epistles to fellow experts, not gallery placards meant to clarify an image for the audience. To quote Frost and Haas (2017):

The ultrasound, in the absence of a fetus and in the presence of the diagnosis of a non-normative body, becomes even more unreadable to non-medical viewers, and we are positioned to only view our opened bodies through the lens of information given to us by our doctors or sonographers — from the thickness of the uterine lining to the number and the diameter of the follicles released from the ovaries and the number and sizes of fibroid tumors present in the womb. (p. 96)When I read them, I have more questions than answers. (What is that? What is that?) I make myself a single arbiter of aesthetic meaning and medical guesstimation, the clinical information so layered, complicated, self-contradictory, and irreconcilable with my embodied experience that it inspires despair.

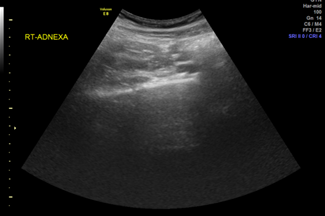

It doesn't help that the unmistakable curved-array trapezoidal shape of the image — whatever it contains — retains the cultural meanings ascribed to it beyond the boundaries of the hospital, which mostly center around pregnancy and motherhood even though the technology was originally developed by engineers for naval purposes (van Dijck, 2005, p. 18). Following a ban on obstetric x-rays as harmful to the fetus in the 1950s, by the 1970s, gynecological exam rooms had been outfitted with ultrasound machines. Power over the visualization of the fetus and the intimate, cryptic female interior shifted from radiologists to OB/GYNs. And by the 1980s, the ultrasound had become an imaging technology popular with patients for its ability to (relatively) painlessly render both the sensitive regions of a woman's body and visible proof of the invisible fetus (pp. 102-103). The denotations and connotations are inextricably intertwined, so the ultrasound reconfigures the female body, pregnant or not, as reproductive.

In 2017, I undergo another TVUS, part of a delayed post-appendectomy workup, to determine if my ongoing pain is related to reproductive structures given the adnexal involvement in the perforation, leakage, and hardening. Dr. Sattva implied he had liberated my fallopian tube from all that mess, but the uterine-colon adhesion remains. The interpreting radiologist writes: "The uterus was retroverted. . . . The recto-vaginal space appeared normal. All pelvic organs appeared to be sliding under the pressure of the ultrasound probe. . . . Normal uterine size. Small subserosal myoma. Unremarkable sonographic appearance of the ovaries." She also observes that the cul-de-sac — the space between the rectum and uterine wall — appeared normal.

I look for the adhesion that isn't there. The retroflexion. The incision scars in the pelvic tissue that aren't there. As for the subserosal myoma that is there, I can't identify it with my untrained eyes.

van Dijck (2005), writing about fetal sonograms, observes: "To accept ultrasound as a neutral information tool — as a purely medical diagnostic — precludes the notion of an embodied subject, who is neither objectified by medical practices nor unambiguously empowered by it, but who actively partakes in an intricate technological process that is also profoundly social and cultural" (p. 116). I'm not pregnant, never have been, never had penetrative sex with a man, and yet I know, I know, that a white man perceived me as a South Asian girl lying to protect her honor and marriageability, and rewrote my medical history in a way that justified that 2014 TVUS, and this is why I experienced a thing that I have quietly, to myself, to my closest friends, called rape ever since.

The most generous reading I have of the 2014 TVUS is this.

To an ER physician, I am just a body, and this is just a job. Dr. Tamas needs to successfully complete her residency. A complicated medical case that reveals her limitations could jeopardize her career. She needs to practice clinical detachment. Building on the microscope and x-ray technology, the sonogram further depersonalizes the clinician-patient encounter. The medical expert probes the patient's body, manually with the transducer and visually through the screen, and arrives at the verdict that will dictate the next step. The diagnostic stare can encompass many parts of the body, but the biomedical gaze focuses on the anatomical regions suspected of harboring pathology (Garland-Thomson, 2009, pp. 28-29). I expect Dr. Tamas doesn't want to feel like the torturer, the rapist, twisting that blunt object she wedged in somehow, because she needs a clear picture, so she presses up, she presses in, and she watches the screen for the moment she can call it quits and bring her findings to the rest of the radiological team.

From a strictly visual point of view, the widespread use of ultrasound imaging and fetal monitoring during pregnancy and labor have publicized the space of the uterus, both by making its contents visually accessible, and more specifically by making them accessible literally elsewhere than at the site of the mother's body. Ultrasound technicians check the status of fetuses by looking at a screen, not the mother's body. (Kukla, 2005, pp. 107-108)This mirrors how radiographers diagnose ovarian cysts and fibroids and rule out PCOS, endometriosis, pregnancy, or pelvic inflammatory disease. After consulting with her advisor and a radiological team, Dr. Tamas wrote this interpretation: "Uterus measuring 7.4 x 4.0 x 5.4 cm EE 8mm. Right ovary measuring 5.4 x 1.6 x 2.9 cm with physiologic follicles, normal A/V flow. Adjacent to the right overy there is a heterogeneous mass with vascularity that may represent an inflamed fallopian tube [emphasis mine] Left ovary measuring 3.4x 1.5 x 3.6 cm with normal A/V flow. No free fluid." She writes that my breathing is non-labored, my uterus is mobile, there is no abdominal guarding, there are no adnexal masses. Some of this is at odds with her own words. Much of it is at odds with my embodied experience of that incident, like my raspy hyperventilation and stiff stomach muscles, and with what I know now about my uterine-colon adhesion. The uterus becomes analogous and interchangeable with the picture on the screen. My body, my self-evaluation, my affect transmissions, all abandoned in the rush to find visual proof.

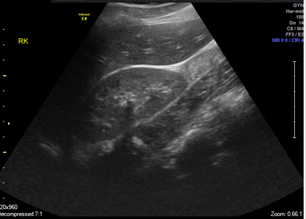

I have called that 2014 TVUS unnecessary, but the truth is I wasn't going to receive an exploratory laparoscopy without one. There is no identifiable moment when a patient chooses to undergo the photographic surveillance in the form of a pelvic or transvaginal ultrasound; physicians take for granted that a woman will have these tests at their recommendation, and there's no moving forward if I don't consent (Kukla, 2005, p. 116). The recommending physician's expertise further constrains this medical surveillance. I went to the ER with gastrointestinal symptoms; Dr. Tamas, an obstetric radiologist, looked for reproductive anomalies. And back in May 2014, based on my reports of periumbilical pain and abdominal pain in the lower left and right quadrants, a GI specialist ordered an upper abdominal ultrasound to rule out hepatitis and pancreatitis, his specialties being disorders of the gallbladder, liver, pancreas, and small bowel. He didn't think about my appendix after I didn't flinch during the rebound test. I also don't have those images, but the accompanying interpretation finds a normal liver, no gallstones, an unremarkable gallbladder, normal flow in the portal vein, normal kidneys of approximately similar size, no lesions. No proof. No more next steps. I can't expect anything else.

My flesh bars exploration and conquest even when pierced by the camera; the medical gaze is "confronted by obscure masses, by impenetrable shapes, by the black stone of the body" (Foucault, 1963/1994) whose secrets remain illegible. Grosz (1994) has stated that "there is no body as such; there are only bodies" (p. 19), which aligns with Hayles' (1999) description of embodiment, where the body's normativity is relative to a historically and culturally contingent set of criteria. She notes that with the widespread use of scientific visualization technologies, like the ultrasound, "embodiment is converted into a body through imaging technologies that create a normalized construct averaged over many data points to give an idealized version of the object in question" (p. 196).

My body-with-appendicitis did not visualize the appendix on ultrasound, just a "heterogeneous mass," and my out-of-range laboratory markers were an amylase level of 111 (30-110 U/L), a lipase level of 488 U/L (10-140 U/L), and a platelet count of 610 K/uL (150-400 K/uL).

CT was my first-line imaging modality, followed by a TVUS, not a graded-compression ultrasound, due to Mitch's suspicion of PID, which overwrote my attestations. The ultrasound serves as the tool of biomedical surveillance and colonial desire, investing a brown girl's womb with a white man's meaning, maintaining the locus of power in clinical radiology (Frost & Haas, 2017, pp. 94-95).

Appendicitis is routinely diagnosed, and appendectomies are a routine surgery in emergency medicine. The idealized, normalized body-with-appendicitis is the body whose appendix is visualized on ultrasound, with classical signs such as a diameter greater than 6 mm, wall thickening, peripheral vascularity, free fluid in the peritoneal cavity, as well as laboratory markers like fever, increased C-reactive protein value, an inflammatory marker, and an elevated white blood cell count. Graded-compression ultrasound, an abdominal ultrasound in which the linear transducer is moved with increasing pressure over the site(s) of maximal tenderness, is considered a highly sensitive imaging technology for detecting these signs, even in thin patients. In this diagnostic protocol, CT and MRI scans are used as complementary imaging modalities for patients with nonvisualization of the appendix on ultrasound (Mostbeck et al., 2016).

This dependency on imaging technology to understand our own bodies builds on a dependency on the visual, a "seeing is a believing" attitude towards disease and distress contingent on the sonographer as the arbiter of meaning. The patient surrenders a little more agency with each look she allows.

Whatever Dr. Tamas saw on the screen, it wasn't my appendix; it was simulacra of my organs and a hard vascular mass. The contents of the uterus, be it fetus or anomaly, are the desired object of the gaze, so all else is inessential. We habituate the schools of thought in which we are trained, and the beliefs and values of the ones who train us. Dr. Tamas' advisor is a white man gynecologist who tells me, based on my medical chart and without an examination, that I'm too young for endometrial cancer, even though Dr. Sattva refers me to him to rule out what he deems a real possibility. Small wonder, then, about Dr. Tamas' bedside manner, her fixation on the objective, decorous image and evasion of my corporeal agony. My experiential knowledge of my recalcitrant flesh should have been as privileged as her ultrasound image, but the screen replaced me. Her interpretation reflects this, and so do Mitch's notes, which first state confirmed diagnosis of PID, confidently authorizing this TVUS even though the initial CT scan confirmed nothing, even though there was nothing but the fact I was attractive and of childbearing age to suggest that I could have contracted it, rhetorically and visually pointing to the colonial and hegemonic value that women are reproductive vessels.

After the TVUS, Mitch's notes state confirmed perforated appendicitis, even though that image also confirmed nothing.

I'm childfree by choice, but my reproductive system is fucked, has always been fucked, and if I desire control over it, I must submit to the medical gaze and to its binary of visibility and invisibility. Even images of my empty uterus — inhospitable to all but fibroids and clots — belong to an assemblage of images in the Western visual rhetorical tradition that shape understandings of reproductivity and pregnancy. The womb, even the empty womb, becomes a digital space, a public theater, a "prosthesis for men to experience a distinctly female biological process" (Frost & Haas, 2017, p. 97). When an ultrasound is conducted diagnostically, internal surveillance becomes a preemptive measure to protect the dream of motherhood to which "good" women aspire. It's rape I'm looking for, in all these images, masquerading as medical protocol. The sonogram, particularly in the context of pregnancy, is not individualizing but homogenizes and normalizes the narrative of maternity and generic representations of the fetus that enter the public sphere (Kukla, 2005, p. 117).

Radiologists are the "speaking eye" of the clinical domain, those who get "to see and to know at the same time, because by saying what one sees, one integrates it spontaneously into knowledge; it is also to learn to see, because it means giving the key of language that masters the visible" (Foucault, 1963/1994, pp. 114-115). Experience is made comprehensible through this observational process, which is also a conquest and an intervention. Van Dijck (2005) writes that medical-diagnostic interpretations are not univocal and are always value-laden, that medical technologies affect our conceptualization and representation of the body. It shapes our collective view on disease and therapeutic intervention as dependent on objective visual evidence and on what the interpreter privileges in her seeing (pp. 104-105).

What counts as observation? As experience? What is medically lost when the patient's observation and experience of the imaging procedure is omitted? Not pictured in 2017: the white man OB/GYN lubricating the transducer with a liberal hand, looking me in the eyes, describing each step of the process in a steady voice so I can plan when to breathe, when to fight the automatic brace. His conversational description of the ultrasound image. My tears, his asking at intervals, Is this okay?, and it wasn't, it couldn't be, and I had no voice to say so because of what isn't pictured in 2014: the transducer, delving deeper than my explorations or the forays of a lover, deliberately twisting through the ring of muscles clenched against intrusion, tight enough to shear away the miserly coat of lubricant and burn with consequent friction. My short, sharp hisses. The head of it a dull, relentless pressure behind the navel, before the sharp unannounced lean to the right, beyond the capacity of the flesh. The room gone nauseatingly sideways as the sandbag in my gut deformed at its insistent push, pushing animal noises from me, even this scrap of control not mine to keep, because nothing is mine under the camera.For the final exam in a precollege biology course, we dissected freshly killed mice, white fur and webbed fascia parting cleanly under the scalpel to show their tiny hearts, buzzing with the last memory of life. Someone nicks a liver or kidney and we crowd around as blood fills the abdominal cavity and the air with the smell of ancient coin, and the viscera are lost to the eyes. That was me, splayed on that metal pan. My sharp, short hisses. My thalaiyeluththu. How could I have known.

I don't know what Dr. Tamas or her TVUS found. She aims the screen away from me, and I, no stoic Karna, am Philoctetes abandoned, prey to my pain. Otherwise, I might have remembered to visibly perform my pain (Siebers, 2004). To keen like a wounded siren when McBurney's point was tapped. To ask for copies of the pictures, which weren't automatically included in my record.

We are so used to stripping epistemology of the affective potential to touch another body that we don't blink at how the digital image of the interior body is sanitized and commodified. Despite the law of proximity, running does not shrink one's demons. Despite the Doppler effect, when recurrent crisis rushes by, its pitch remains as shrill.

In what terms must patient observation and experience be described to be accepted as essential companions to medical imaging? I am a non-medical viewer, not a sonographer with fluency in ultrasound technology, with the ability to translate sound waves into a personal understanding of the body's interior. By collecting these images for self-deterministic means, I am trying to engage in a decolonial feminist sense- and meaning-making, destabilizing how I am viewed, what is viewed, why I am only viewed when I telegraph my pain visually; why even when my pain is visible, what matters most is the diagnostic image, which reinforces and reproduces social and political identity in our bodies, which refracts knowledge and experience of suffering. In crisis, persuasion is extraneous to my becoming the subject of medical imaging. Refusal on my part resembles suicidal ideation.

Where should I say, where does it matter, if it matters at all, that a lawyer advised me that I had no grounds for a lawsuit, because "emotional distress cannot be compensated unless there is a physical injury caused by malpractice" (V. Wickman, personal communication, August 25, 2016). I have no physical injury save the ruptured appendix and purulent tissue I arrived with, as captured on the pictures I never saw, and because multiple forms of medical imaging are routinely used as diagnostic in the ER, there is no malpractice. The absence of enthusiastic consent is an issue in sexual assault, not in medicine.

The ultrasound image I never saw did not clear up the mystery, didn't prove I needed an appendectomy, didn't place me in the surgical rotation, but did prove I wasn't physically injured by the procedure itself, foreclosing legal recourse, or what I really wanted, accountability.

In their discussion of imaging around pregnancy and infertility, Frost and Haas (2017) note: "the power of desire, surveillance, and fragmentation lies with all interested actors in the fetal ultrasound network. Thus, the agency to subvert and resist this power does, too, albeit unevenly distributed across the network" (p. 103). Actors in this network include physicians and sonographers, women patients, feminists, social justice advocates, rhetoricians, media studies scholars, and medical professors, to name a few, all with observations and experiences. The human sensorium in its whole, wild, comprehensive range must precede and accompany digital imaging and diagnosis. I don't have the power to individually change the system, but I am an actor in this network with observations, experiences, traumas. Mitch and Dr. Tamas have gone on to establish private practices, and my body is likely forgotten, one of hundreds they've dealt with, dismissed, misread or mistreated in their careers.

When you look at these pictures, with your academic, medical, or artistic interest, consider what is illuminated in the negative, shadowy space made visible by sound: causes of pain in a trapezoidal view, ovarian cysts, fibroids, septic hardening around a fallopian tube, never legible or legible enough to warrant treatment. The sonographer's discourse is a series of facts they locate in the images they produced. Consider the cost of making them.

(–89. Knitted Guts)