50. Peyththai

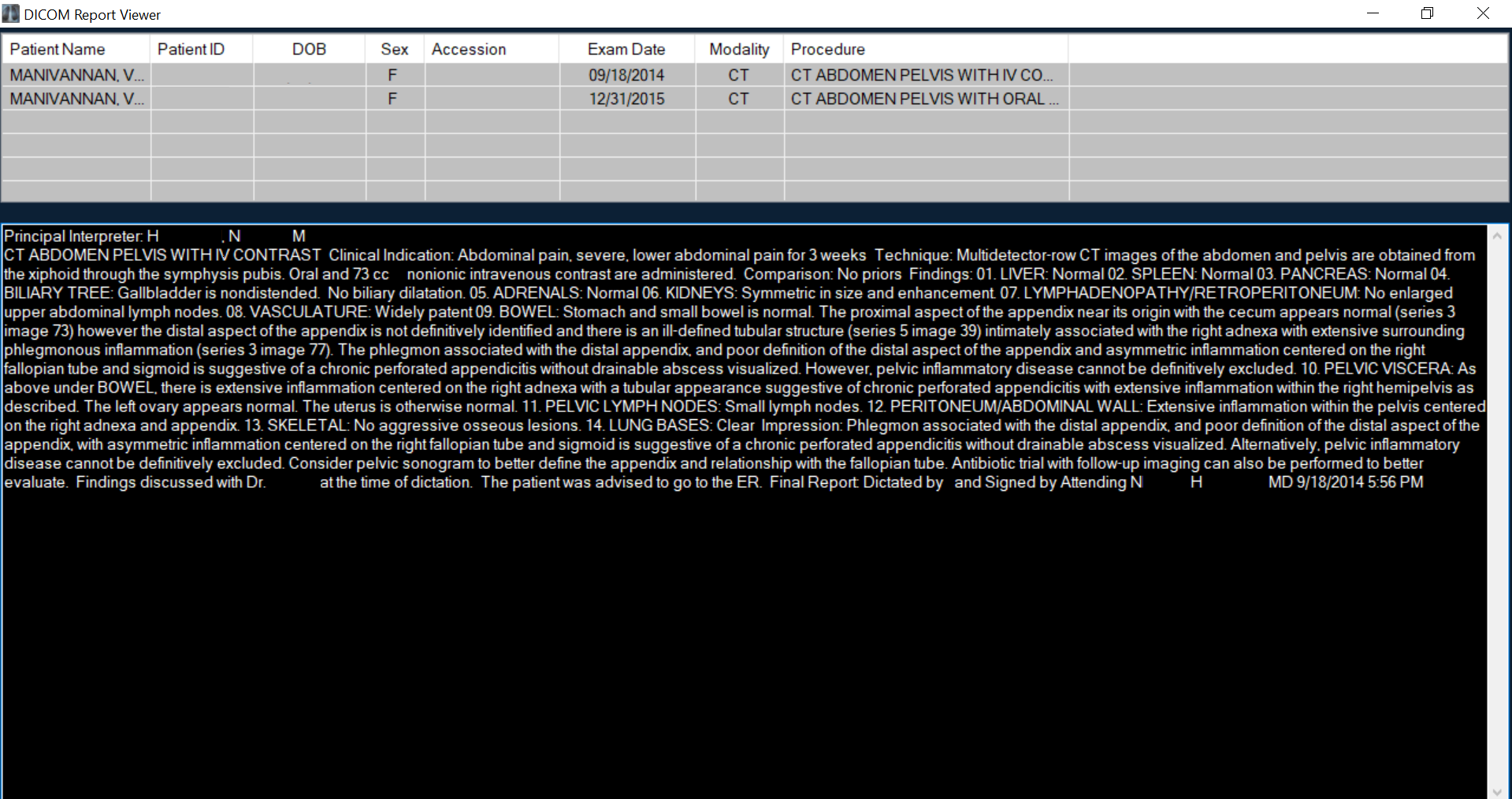

The principal interpreter writes:

"CT ABDOMEN PELVIS WITH IV CONTRAST Clinical Indication: Abdominal pain, severe, lower abdominal pain for 3 weeks Technique: Multidetector-row CT images of the abdomen and pelvis are obtained from the xiphoid through the symphysis pubis. Oral and 73 cc nonionic intravenous contrast are administered. Comparison: No priors Findings: 01. LIVER: Normal 02. SPLEEN: Normal 03. PANCREAS: Normal 04. BILIARY TREE: Gallbladder is nondistended. No biliary dilation. 05. ADRENALS: Normal 06. KIDNEYS: Symmetric in size and enhancement. 07. LYMPHADENOPATHY/RETROPERITONEUM: No enlarged upper abdominal lymph nodes. 08. VASCULATURE: Widely patent 09. BOWEL: Stomach and small bowel is normal. The proximal aspect of the appendix near its origin with the cecum appears normal (series 3 image 73) however the distal aspect of the appendix is not definitively identified and there is an ill-defined tubular structure (series 5 image 39) intimately associated with the right adnexa with extensive surrounding phlegmonous inflammation (series 3 image 77). The phlegmon associated with the distal appendix, and poor definition of the distal aspect of the appendix and asymmetric inflammation centered on the right fallopian tube and sigmoid is suggestive of a chronic perforated appendicitis without drainable abscess visualized. However, pelvic inflammatory disease cannot be definitively excluded. 10. PELVIC VISCERA: As above under BOWEL, there is extensive inflammation centered on the right adnexa with a tubular appearance suggestive of chronic perforated appendicitis with extensive inflammation within the right hemipelvis as described. The left ovary appears normal. The uterus is otherwise normal. 11. PELVIC LYMPH NODES: Small lymph nodes. 12. PERITONEUM/ABDOMINAL WALL: Extensive inflammation within the pelvis centered on the right adnexa and appendix. 13. SKELETAL: No aggressive osseous lesions. 14. LUNG BASES: Clear Impression: Phlegmon associated with the distal appendix, and poor definition of the distal aspect of the appendix, with asymmetric inflammation centered on the right fallopian tube and sigmoid is suggestive of a chronic perforated appendicitis without drainable abscess visualized. Alternatively, pelvic inflammatory disease cannot be definitively excluded. Consider pelvic sonogram to better define the appendix and relationship with fallopian tube. Antibiotic trial with follow-up imaging can also be performed to better evaluate. Findings discussed with Dr. at the time of dictation. The patient was advised to go to the ER. Final Report: Dictated by and Signed by Attending NH MD 9/18/2014 5:56 PM"

To me, the radiologist says, "Your pelvis looks like a bomb went off. How are you even standing right now? And you say this started a month ago? It's unbelievable."

I am Eelam Tamil. I know what a pelvis looks like when a bomb goes off. These slithering grayscale pictures aren't it.

My appendix might have burst a month ago at the end of August, but the smaller tears must have started nine months ago, when the pain began and I indulged it with doctor visits, pathology tests, diagnostic imaging exams. The timeline supports the admitting radiologist's initial and primary suspicion of chronic perforated appendicitis. In either video, you can see what she means if you even vaguely know what to look for: the psoas, distinct; the cecum, distinct; the appendix, diffusing into balloons of timberwolf gray as the dynamic processes of my body swell and shrink. Distal appendicitis, I learn later, can be a diagnostic challenge for radiologists, because the cecal base remains unchanged. At 0:03 on the coronal plane and 0:06 on the axial plane, I imagine I can see a thickened distal appendix with focal periappendiceal inflammatory changes, and associated phlegmon, or non-specific, ill-defined, heterogeneous soft tissue inflammation.

As I walked down the block to emergency outpatient radiology for this procedure, Dr. Jiang's referral in hand, I told Amma on the phone I am dead already, and the camera proves this. What is captured is a body without a person, a body renovated by pain into a haunted hotel for any vagrant sensation looking for a room to let.

CT scans use X-rays to visualize thin cross-sections of the body that can be recombined into three-dimensional moving representations of tissue and organs. As videos, CT scans restore temporality to the image, visualizing the body in flux over a period of time, and also as an artifact tied to one moment in time, the day it was recorded, making it simultaneously timeless and dated, moving and constrained. Dolphin-Krute (2017) likens the process of medical imaging to portraiture, snapshots that date the body, or in this case, a motion picture that endows the body fixed-in-time with a bounded temporality. She also notes: "There is also a key feature in the moment of the creation of a medical image that cannot refute the very invisibility of the ghostbody: the very act of creating a medical image is an admission of an invisibility that cannot be overcome without technological means, though always with no guarantee that the technology will be enough" (p. 36).

The technology has never been enough. The legitimacy of the transparent body is contingent on the subjective perception of machine operators and interpreting radiologists, which is encoded into the production of the image and shaped by social context and specialized knowledge, skill, and power (Rice, 2013; van Dijck, 2005). In chronic appendicitis, classic CT scan findings include a dilated appendix, periappendiceal fat stranding, wall thickening and surrounding edema, abscess, phlegmon, calcified appendoliths, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. Visual confirmation then leads to surgical intervention. This is not what happened for me.

Dolphin-Krute (2017) asks: "In a medical image, is the moment of its creation the moment in which the body is inside the [imaging machine] or the moment when it is viewed and interpreted by a doctor? If the latter, what if the doctor fails to adequately or correctly perform this interpretation, is the image still completely created? Is it the body that has produced the image, at the moment the magnetic fields around it started to change, or the machine itself, as it transmitted the data it gathered? In a relationship wherein a ghostbody is viewing an image that may or may not be clearly indicative of their own temporal standing and its uncertainty, such a statement does not hold true. What if, even from the moment at which the image was created, the ghostbody is already not surviving?" (p. 37)

I was not surviving; I was forming a new body from the infection that my body had cordoned to protect itself, an appendiceal city ringed by walls within walls that no machine could detect. My diagnostic scans revealing a transparent and clinically insignificant body, but dying rendered me radically opaque. The machine gathered useless data that day, transmitted an inscrutable picture to the computer screen, where the human eye reads war. My body waging suicide terrorism against itself with impunity, until the city is stormed like Kilinochchi, its infrastructure destroyed, ghosts left in its wake.

In both videos, part of the bowel is normal, other parts swollen and unbounded. I have barely eaten in a month. I am asked about anorexia, but no, like a Tamil ghost, I am dangerously obsessed with food, to the point that when I am handed three bottles of barium contrast and told it tastes so revolting most patients only get through one, I chug all three. I am not sated. I am like Kabandha, the gandharva chief cursed to be a long-armed torso with an insatiable appetite for mocking the sage Ashtavakra, forced to wait for Rama to perceive my nature and set me free.

If Kabandha is a specific name for my gut, then peyththai is my name: what Amma calls a hungry ghost, the Tamil version of the Sanskrit preta. Those who possessed excessive greed or desire in life are reborn as peyththai to live out their karma. Peyththai are ghosts at the borderlands of even ghosthood, as they lack a fixed form, having become their bad karma, but they are more bodied than a spirit. They are air and ether without earth, water, and fire. As incomplete beings, they cannot eat or drink and are consumed by hunger and thirst. It is the duty of surviving family and Brahmin priests to feed the peyththai with rice balls, as it grows hungrier through each stage of grief, and each set of rice balls helps it form its new body and progress towards the next stage of samsara.

Ghosts are innately disabled, having lost their bodily capacity (Dolphin-Krute, 2017). The peyththai is also a disability metaphor, a culturally specific way of understanding Cotard's syndrome (Chandradasa et al., 2020). And why not non-apparent chronic pain as well? It is said that peyththai suffer intensely from cremation to karmic rebirth. Like so many Ammas, mine would scold pisasu or peyththai when she caught me sneaking sweets, unaware that she was telling my future.

Dolphin-Krute (2017) says: "The promise of photography as a documentary tool, creator of a visual index of difference, should not be trusted. Ghostbodies can rarely be captured on film, precisely because of this capturing. Photography, as a tool used to document as many physical differences as the eye can see, has effectively killed, not captured, ghostbodies" (p. 1).

Peyththai are air and ether, and CT scans are atlases of density: high-density matter, like bone, shows up more brightly (white); low-density matter, like air and fat, show up more darkly (black); and everything in between, like soft tissues and fluids, appears in shades of gray. As the machine reads my body, my body inhabits the character of the machine. Grayscale disguises most of my embodied experience. The translucent genitals indicate womanhood but you can't tell I'm Tamil or queer or in considerable pain from having to hold still. In the coronal view, I am a body with organs, without personhood. In the axial view, I am inhuman, a strange pool of multiplying amoebae. Or rather, I'm an everywoman, a canvas for imagination in the absence of biomedical fact. Everyone imagines zebras when horses are right there.

According to van Dijck (2005), "Medical imaging technologies have rendered the body seemingly transparent; we tend to focus on what the machines allow us to see, and forget about their less-visible implications" (p. x). Paradoxically, the mediated body that appears transparent is stratified and contested: the alleged objectivity of the image belies the ethical choices made by radiologists and interpreters. The medical and cultural assumption is that imaging instruments photorealistically, and thus objectively, reveal the body's interior; additionally, medical imaging contributes to the Western ideal of the totally transparent, knowable body, the body that can be cured (pp. 4-6). Seeing is curing only if there is something that is seen. Like the ideology of cure, biomedical imaging is a contradictory mosaic. In identifying an affliction, it saves lives, manipulates lives, prioritizes certain lives, turns a profit, perpetrates and justifies violence, promises an end to the malady (Clare, 2017, p. xvi). As an ideology, cure flourishes in the medical-industrial complex, where it revolves around locating and eradicating abnormalities within a bodymind or bodyminds at large, working in and through diagnosis, treatment, management, rehabilitation, and prevention to do so (p. 70).

In a WhatsApp conversation about these pictures, Sara says: "Things have a way of becoming clear sometimes and other times they remain tireless whispers wreaking unimaginable havoc on us" (S. Fuller, personal communication, August 17, 2021).

In the biomedical complex, the peyththai is better than the real body because the peyththai, incorporeal and fragmented, can be viewed with impunity, unable to return the gaze. These are not autopsy reels, but they locate the patient's voice in a "dead" body, not in a living voice, much like early anatomical and pathological illustration.

When I return to the hospital in January 2015, compelled by dysmotility and a searing, ripping pain in my LLQ, LRQ, and suprapubic regions during digestion, I am braced for more diagnostic imaging, for more pictures of peyththai or Kabandha awaiting prey, both of which will stymy cure, neither of which will catalyze care. In this follow-up visit, Dr. Sattva looks the same as he did in the ER, smiling in his white coat, glasses pushed to the bridge of his sharp, straight nose. He could be my cousin. It's a little disconcerting, talking to him while sitting upright, given that most of our encounters consisted of him looking down at me on a hospital bed or gurney. As when I met him in the ER, he does not exude superiority.

"I know it sounds weird," I confess, "but I can feel everything moving. Sometimes it feels so full, it's better not to eat." I use pronouns without referent, always, when I'm fumbling through some unproven and complicated new symptom. It's a tricky measure of self-protection: the physician assumes which body part I mean by it, and I can judge the physician based on their assumption and then decide if it is safe to proceed with the truth as is, or if fibromyalgic cunning is needed.

Dr. Sattva lifts his eyes to the ceiling, the same move I use in the classroom to indicate deep thought. "So, as you probably know," he says, "any time you cut into the abdomen, you run the risk of abdominal adhesions. I think you know what those are, but they're these tight fibrous bands, like scar tissue," he presses his hands together like a supplicant, hard, demonstrating the difficulty of sliding his palms across one another, "that cause the organs to stick, and prevent them from sliding. When I opened you up, I was really scared for you. The tissues were so hardened."

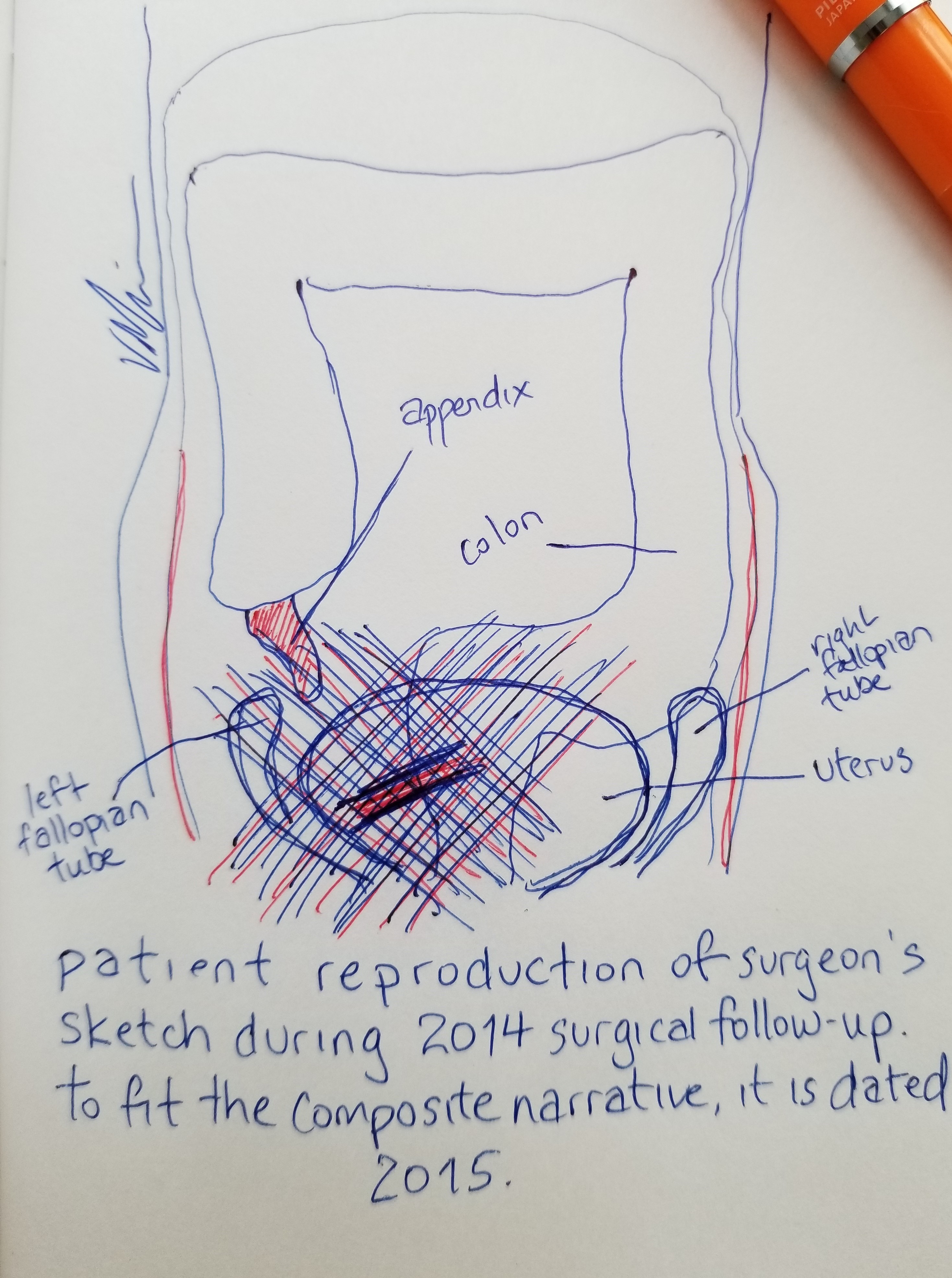

"Is it weird to ask what it looked like?" I say instead. Dr. Sattva lights up with a pedagogical interest I recognize from myself. He rifles through the papers on his desk, turns over a half-completed medical bill, and draws a sexless torso and an approximation of a large intestine in it. "Okay, so this is your colon. This," he says, drawing a circle over the gut, "is your uterus, sitting in front of it. This," drawing a fiery tongue on the lower left colon, "is your appendix. Was. The peritoneum covers all of this viscera. And all of this," cross-hatching over the uterus and colon, "was a hardened mass. Like layers of paper that's been wet and left to dry. It was like scraping tissues to get it all apart. I separated as much as I could, but your uterus and colon," he draws two heavy-handed lines between the circle and the gut, "were fused together, and given your state, I worried that trying to separate them would resolve in a puncture, and prolonged surgery or infection."

Even though it was a laparoscopic surgery, he raises his joined palms slightly to illustrate how my uterus would not be lifted, and I can feel the wet heavy ball of it in my own cupped hands, resisting levitation. He seems so earnest. I don't tell him that the GYN he referred me to — an older white man, incidentally the advisor to Dr. Tamas, who administered the traumatizing TVUS in the ER — looked me up and down in the hallway in front of his office, glanced at my records, and dismissed the possibility because Endometrial cancer? You're too young. You look fine. Two weeks post-op at the time, I was too tired to follow up with anyone else.

His metaphor, wet paper and layers of tissue, echoes the kind of poetics I use with my friends, and that — angry, exhausted, my filter whittled to scrap — I reverted to in the ER. How lucky I was that he was the attending surgeon that day, since biomedicine's ocularcentrism asks me to leave my body behind in patient narration about pain, even though pain emerges and is made sense of through intersubjectivity, using modalities other than sight and the language of a positive science: through vectors that, like language and pain, are affective, corporeal, co-constructed, and contagious (Padfield, 2011; Morris, 2000).

Dr. Sattva continues: "You're eating and having normal bowel movements, even if they're painful, so it's unlikely you're obstructed. But a CT scan can at least tell us if surgical intervention is essential, so let's proceed with that." He hands me the radiology referral. I think of all the dismissals and misdiagnoses in that year that led to this red bridge between my uterus and colon, which explains my spate of complaints in the months since the surgery: the "fullness" that worsens during menstruation, the "pulling" that occurs during a bowel movement. It's hard to mask the rage.

Although they're considered a diagnostic modality for adhesion-related complications, like bowel obstruction or ischemia, abdominal CT scans are unlikely to detect the visible presence of adhesions. My 2015 CT scan affirms the post-op restoration of my visually mystifying status: Unremarkable CT enterography. Stomach, small bowel, and large bowel are normal. There is normal mural thickening and enhancement. No peri-enteric abnormality. No right lower quadrant inflammatory changes are seen at this time.

It takes a visual confirmation of presence, an image with its aura of objectivity, to authorize further inquiry. The image, however, is clear. The ghosts I feel so clearly evade the camera's eye.

The 2015 abdominal CT scan with barium swallow and IV contrast depicts this absence. There is a ghostliness to the image, a naked, solid mass of gray, with outlines of skin, bone, tissue, and organs and their contents glowing faintly within. My pelvic bones are like smoothly carved ivory, and above and between them, my gut is a dark corrugated drainage pipe. This body — that is, the technological capture of this body — feels inhabited by another body, a ghostly possession by the technicians and interpreters who do not appear in the image but have dominion over how it is read and recorded, what becomes of it in the end. Because they do, this body is already a ghostbody, already potentially slated for dismissal. On top of that, it's a container of other ghostly presences, organs made invisible by rays that aren't designed to see them or the processes of a living body in flux, or, in this case, the appendix that is no longer there.

Is a lost appendix worth grieving? Was its vestigial presence worth the years of grief it gave me? How can I explain the lack of closure that manufactures these questions, the dissonance between the flesh claiming its pain and the biomedical gaze, on seeing nothing, calling it psychosomatic?

Dyed in barium, I glow, kaleidoscoping from view to view. I am a starving peyththai, more naked and less substantial in this film than I am on the narrow examination table, in the claustrophobic tunnel that ferries me between the worlds of material presence and intangible computerized data. My untrained eye sees Rorschach blots instead of organs, apparitions instead of scars. This is a moving picture of absence that can't fully refute the peyththai's presence. If you proceed frame by frame, you can watch me incarnate, membranous, from one form to the next. The black holes of a gut full of air or fluid. The steely shape of a liver. The gray desert where my appendix used to be. The peyththai contains no-body and multiple bodies, always on the verge of coalescing, always becoming-anew.

This medically insignificant film is the fact driving the conclusion that, though I am suffering, nothing is wrong. I encounter a "fact" like these scans, and I know that the facts aren't in it. In 2015, where is my adhesion? In 2014, where was my ruptured appendix? In 2007, where were my musculoskeletal pain, my neuralgia, my fatigue? My medical history is littered with partially birthed images squalling for thorough interpretation. Through each act of viewership, Dolphin-Krute (2017) says, "the balance and link between information and image is changed. A patient may see only an image, information not fully understood. A technician may see the image only as a process or operation. A doctor may see only the information it conveys, the aesthetics rendered irrelevant as so many are seen and must be ultimately processed, into diagnostic or prognostic information. . . . It is in the nature of this interpretation to be multiple. As new information comes to light, as opinions surrounding the body represented are gathered, as new experiences of, within, the body are had, the image itself comes to function differently. . . . What showed nothing, seemingly, can become a frustrating reminder of an unlocatable yet definite presence" (p. 35).

As viewers, we accept the relationship between this slideshow of photographed cross-sections and real bodies, but although seeing and curing are equated in medical and media representations, imaging does not simplify bodies, does not promise a solution. As van Dijck (2005) says, "We can never assume a one-to-one relationship between image and pathology: looking at a scan, medical experts may identify signs of potential aberrations, but their interpretations are not necessarily univocal" (p. 7). The monogeneric strategies of interpretation deployed in biomedicine have serious ramifications for knowledge production and the construction of the pained body. Digital rendering presumes a well-behaved body that will willingly surrender its signs, but as Padfield (2011) notes, "Chronic pain disrupts narrative, and perhaps having that seen, heard, and acknowledged is more important than trying to frame the narrative linearly" (p. 253).

I am tired of objective, emotionally-distancing language and vision being the sole modes of meaning-making, yielding taxonomies that mystify chronic pain and images that, like a systematic cover up, seal my body's truths beneath the myth of one-to-one objective photographic representation (Whelan, 2009; Kleinman et al., 1998). Baszanger (1998) observes that clinical treatment of pain should draw on diversified knowledge, but patients' words are merely an indication (pp. 148-149). If it is through "the regular alternation of speech and gaze [that] the disease gradually declares its truth" (Foucault, 1963/1994, p. 112), the patient who complains of distress with no visible symptoms is automatically unreliable, especially in the contemporary biomedical complex where malingering for welfare is a common accusation. I am assured the machine sees everything, but this one fails to capture my conjoined uterus and colon, and failing to capture it, kills its possibility, leaves behind a pey.

Without a conclusive image to corroborate subjective certainty, I am stranded, alienated from clinicians who point to these scans as incontrovertible evidence of normalcy and wait for me to disavow my pain (Rhodes et al., 1999; Reventlow et al., 2006; Wolfe, 2000). What I end up with is another artifact that impugns my credibility — and a very specific construction of a self in pain whose pain cannot be authenticated by modern technologies of capture and who thus threatens the stability of (medical, scholarly) expertise by presenting an unreliable body whose invisible parts can't be parsed (Foucault, 1963/1994). Diagnostic imaging allegedly "sees" specific elements of the body, isolating (and helping to define and normalize) social behaviors like the expression of pain. Subjectivity becomes value-laden alphanumerical code, weighted with social status. Suffering becomes not only biomedical datum, but also social status, to be bestowed or withheld (Morris, 2000).

All looking is directed, and so visual medical data is a co-constructed performance (Dumit, 2004; van Dijck, 2005; Teston, 2017). In her discussion of the backstage methods of biomedical professionals, Teston (2017) suggests that the visualization and assessment of biomedical evidence, like radiological images, is a way for clinicians to cope with the corporeal indeterminacy of the opaque body and the materiality of disease (pp. 14-15). Biomedical imaging is radiological cartography, providing surgeons with navigational evidence without them having to cut into the flesh, in the form of a snapshot of a body in flux, whose biological processes are otherwise undetectable (p. 34). The diagnoses offered by imaging technologies transform our corporeal bodyminds into artifacts more legitimate than ghost stories: charts, symptom and medication logs, images on light boards and screens, physician notes. These images wield cultural and political forces; they prognosticate and influence medical decisions (Clare, 2017, p. 41). But my fibromyalgia, my appendicitis, my adhesion, all evade visualization.

The physicians lose us in their visual field when they look at us too directly. When they capture us on film and crow over the achievement, they do not know what they have in their hands; they can't fathom the ghostbody that simultaneously comes into focus and slips the trap of the biomedical gaze.

(–70. Sisyphean Persistence and Reward)